Comment on Ian Davidson's piece --

Abena Sutherland

To take only one island, Douglas Oliver has an interesting idea: the K.O. moment. Covering a European title fight he transcribed the action into his notebook: "Afterwards, I would find that my handwriting had become stuck in continuity of either vowel or consonant too: 'Moo lands a goooooood onnne', an entry would read. 'Faaaa(s)t hooooook frrom Viito'. The intervening punches would be missing." (Three variations on the theme of harm, p70) The fight is a clear, harmful event for Oliver, each punch almost pure: "On its own, each punch creates no language, just a daze of amazement, an almost-empty instant of cruelty." (p71) The punch is "the moment of change", it is "direct transparency of will".

The self which bears the will and "loyalty" falls, but there is another "apparently plenary self" (p62) which retains control of the falling body. The fallen self is defenceless on the floor. In The Harmless Building boxing is referred to as the most "capitalist of sports". You never did see it coming; you saw it coming and you couldn't do anything about it. In the long virtual poem or poem of virtual worlds, 'The Video House of Fame' (in Arrondissements), there are constant duels, visor and computer, chosen character then chosen enemy:

The island might be that moment between two events. Like the body of a bird between wing beats. Or it might be the point at which, standing straight up to take your medicine, all defenses are down and the knock out punch gets through.

The knockout catches the mind between its tiniest islands, in a moment when the instant has not quite entered memory to be filled with form. (p60)

- from Ian Davidson's An Island that is all the World – an unfinished conversation

To take only one island, Douglas Oliver has an interesting idea: the K.O. moment. Covering a European title fight he transcribed the action into his notebook: "Afterwards, I would find that my handwriting had become stuck in continuity of either vowel or consonant too: 'Moo lands a goooooood onnne', an entry would read. 'Faaaa(s)t hooooook frrom Viito'. The intervening punches would be missing." (Three variations on the theme of harm, p70) The fight is a clear, harmful event for Oliver, each punch almost pure: "On its own, each punch creates no language, just a daze of amazement, an almost-empty instant of cruelty." (p71) The punch is "the moment of change", it is "direct transparency of will".

The boxer imposes 100 per cent willMaximum force from the flow of fighting. "Nowadays, grandly, I like to imagine a 'philosophy of the knockout', according to which a punch can impose on the victim an experience of an instant without content." (p60) What follows from the quote that Ian has picked out (above) is this: "If you've ever been knocked out, you know that the K.O. strikes either to our sheer surprise or when we are too weary or addled to have an 'I' in consciousness to defend."

punching harm into harm in sadistic rhythms. (p72)

The self which bears the will and "loyalty" falls, but there is another "apparently plenary self" (p62) which retains control of the falling body. The fallen self is defenceless on the floor. In The Harmless Building boxing is referred to as the most "capitalist of sports". You never did see it coming; you saw it coming and you couldn't do anything about it. In the long virtual poem or poem of virtual worlds, 'The Video House of Fame' (in Arrondissements), there are constant duels, visor and computer, chosen character then chosen enemy:

Reflection places plenitudePunching at yourself; wrestling with an angel and the responsibility of care: Oliver ends 'The boy knocked out' -

into a void: it teaches me

what to do with this

Narcissus. Blast

him out. From the

shattered mirror

slowly fall the prince's

knife blades

Caught still in my earthly fight,

masochism

to empty the instant of responsibility.

An Island that is all the World

– an unfinished conversation over a number of incomplete rounds. I finish, as always, on the ropes and gasping for breath, casting glances at my corner and wondering if I'll ever reach it.

Ian Davidson

. . . pages become bright islands floating in darkness . . . (p53)

The island might be Brightlingsea, a town down a road like the neck of a womb that ends in sea and swamp.

The islands are almost still places in memory . . . (p53)

The island might be the Yachtsman's pub in Brightlingsea. Oliver smoked small cigars and played pool with the unhurried calm of the snooker player. So maybe he was the island.

The island centre is a darkness through which all islands are linked together. (p53)

The island might be Oliver's seminar series in the University of Essex. It's where I first read Creeley. As I sd to my friend John I sd. Or maybe the Creeley poem was the island.

The island might be Oliver, sitting in his front room in New Street or Sydney Street, working at a typewriter while I walked past on my way to another pub.

Sometimes I return to the sea scenes of childhood to seek the origins of whatever stabilises myself in space and time. (p46)

The island might be my room overlooking the Colne from a poor terraced house.

The island might be surrounded by a sea of whisky, or it might be my car, it's floor littered with empty cigarette packets.

None of these islands were all the world to me.

I never hear rich calm voices in my imagination. I hate them. But I'm interested in people who do.

. . . once we touch more profoundly natural unconscious sides of ourselves all the cultural rubbish falls away and we recognise a deep kinship, an international kinship . . . (p92)

I don't think culture is inessential, or more or less than an unconscious, or that there is a 'spirit' in a poem. But when I say that I don't think I don't quite believe it, or that I'm right, and I'm interested in people who do think that and try to argue it.

The island might be Oliver in my imagination writing in a room in Paris.

When I lived in my literal home island, at each moment the outer British world became part of the deep self creation: my family life, my village, the near town, distant friends . . . (p81)

The island might be Oliver's Englishness which he took everywhere with him as he traveled the world; like a character from Graham Greene who never could quite grasp how slippery everything is. Or maybe he did but chose not to.

Though as a foreign observer I was safe . . . (p95)

The island might be Oliver's place of attack against the choppy waters of literary theory.

The island might be Oliver's archive in the library at the University of Essex.

The island might be Oliver performing his poetry.

It was verray intense . . . (p92)

I don't really believe in stopped time or the instant. My life is more fluid, or liquid. One moment flowing into the next. But then again one time in a pub in St Albans in 1980, and honestly I hadn't been drinking, the whole scene slowed down and the voices went slurred and the faces slipped like a Francis Bacon painting.

If a past memory comes into the present and simultaneously the present is vivid, then the past shares in the immediacy; for a second or two I sense a potential to bring all the intervening life into the immediate as well. (p105)

I come from a bilingual culture; hybridity is my 'natural' state. It is for most people in the world. Others seem to think it affectation or fancy – a kind of willful construct. They believe in the possibility of a stable or essential relationship between language, culture and geography. The popularization of linguistic and literary theory in the 1970s and 80s validated my life experience rather than challenged it. Kind of sad when you think about it.

Unity of form disappears into ambiguous dark whenever we examine it analytically, but its heart is always like the beating heart of a poem: it is the precious origin of our lives' form, or of a true politics. (p107)

The island might be a place of nostalgia, of longing for a certainty that, for some, is only ever a promise.

It could be any moment in any adult life when a past island is left behind; a new one not yet reached. Unfortunately for them, poets often get their work out of such tenseness; they're washing about in a mid-sea . . . (p78)

The island might be a raft made out of the debris that is left after global capitalism has swept through, and the poet a Crusoe figure trying to construct a meaning from the bits and pieces long after capitalism has constructed a number of other possible futures and turns to point and laugh with many empty voices.

And an island might be a place for the avant-garde to hang out mulling over what things might mean while the rest of the world goes scudding past. A kind of post-garde with poor fashion sense, bad haircuts and ethical concerns and endless bickering over definitions and readings in places not designed for readings and picking over the debris of capitalism while capitalism consumes and discards.

In a poem each stress is held in memory and perceived as a unity of sound, meaning and special poetic emotion . . . The stress centres a tiny island in memory. The centre of the island is occluded; it is the moment when we believe the stress actually happened. (p57)

I have never been at home anywhere. Most people haven't. Or if they have they rarely need to bother to write anything down so you won't have heard of them. It's all around them, written in the material of their lives.

Separating from England almost cleaved my unconscious identity in half, an irreparable harm I'd done. (p91)

I live on an island and have done most of my life. The island might be Ynys Mon, or Holyhead Island. As I read I might be constructing an island as a reflection of my own island rather than inhabiting his.

I might be doing him an injustice. This reading might be a misreading.

The island might be a boxing ring. It might be a place of peace or a place of conflict. The boxing ring might be middle class family life in the South of England.

The knockout catches the mind between its tiniest islands, in a moment when the instant has not quite entered memory to be filled with form. (p60)

The island might be the:

. . . deep whole healthy self that is constructed of all unconscious vividness built into it . . . (p103)

If he has a deep whole self how does he know it's healthy? Is there no doubt? Maybe in the end we're rotten inside, or some of us are, and all we do is for the wrong reasons. However hard I try to be selfless I end up being selfish. Or is that simply the result of my being ambidextrous, of the left hand never knowing what the right hand is doing. Or classic Gemini tendencies. I think, see, that all the interesting stuff takes place at the edges, just out of sight, stuff I catch out of the corner of my eye. Glances. Glancing blows that keep me rocking. Inside is full to bursting with organs. So the idea of the rays of the object brought to a focus, is replaced by constant blurred movement. No still center. No perfect rest. No possibility of sustaining a position, or an opposition, and a metaphysics of attention is replaced by movement. Movement between countries, on the flickering screen, from lover to lover, from job to job and from poem to poem. Never sitting still and thinking about anything. How to count the loss of that.

I hate authoritative voices. They make me want to spit. Or otherwise misbehave. I don't like the idea of an island but I've chosen to live on one. And it's an island attached to another island. So maybe I like the idea of an island so long as it's in relationship to a lot of other islands. And Oliver almost says that when he says that 'all the islands of ourself expand out to the larger self and the larger self takes place in the great unconscious universe . . .' and my heart goes pitter patter and I reach for the word intertextual or rhizomatic to pin it down and then I read the next bit 'always as itself' and how 'its heart is the precious origin of our lives form'. Islands are the temporarily visible high points of consciousness, arising out of the unity of the unconscious. In the same way that underwater all physical islands are linked by the unity of the world, all 'memory' islands are linked via the unconscious. Each island has its own bordered unity and each person has their own bordered unconscious. It's a tempting visual analogy. It gives a sense of security, and a sense of endless possibility within that security, where all islands are possible in their recombination. But if there are borders to the unconscious, and each conscious island, how can we recognise those borders without consciously crossing them? To recognise the border is to acknowledge the other side and challenge any notion of unity. What is on the other side? Will acknowledging that cause disunity?

An island might be like those islands where strange animals still live cut off from the rest of the world and missed out on mainstream evolution and where words still mean what they say. Why did Oliver go on so much about the similarities and differences of avant-garde and mainstream poetry? Is it because he thought somewhere, through all that, there was an island where he could write the pure poem?

There is no island that is all the world. There isn't. Show me, go on, show me.

-------------

Page references are to 'An Island that is all the World' from the Paladin selection Three Variations on the Theme of Harm.

Ian Davidson

. . . pages become bright islands floating in darkness . . . (p53)

The island might be Brightlingsea, a town down a road like the neck of a womb that ends in sea and swamp.

The islands are almost still places in memory . . . (p53)

The island might be the Yachtsman's pub in Brightlingsea. Oliver smoked small cigars and played pool with the unhurried calm of the snooker player. So maybe he was the island.

The island centre is a darkness through which all islands are linked together. (p53)

The island might be Oliver's seminar series in the University of Essex. It's where I first read Creeley. As I sd to my friend John I sd. Or maybe the Creeley poem was the island.

The island might be Oliver, sitting in his front room in New Street or Sydney Street, working at a typewriter while I walked past on my way to another pub.

Sometimes I return to the sea scenes of childhood to seek the origins of whatever stabilises myself in space and time. (p46)

The island might be my room overlooking the Colne from a poor terraced house.

The island might be surrounded by a sea of whisky, or it might be my car, it's floor littered with empty cigarette packets.

None of these islands were all the world to me.

I never hear rich calm voices in my imagination. I hate them. But I'm interested in people who do.

. . . once we touch more profoundly natural unconscious sides of ourselves all the cultural rubbish falls away and we recognise a deep kinship, an international kinship . . . (p92)

I don't think culture is inessential, or more or less than an unconscious, or that there is a 'spirit' in a poem. But when I say that I don't think I don't quite believe it, or that I'm right, and I'm interested in people who do think that and try to argue it.

The island might be Oliver in my imagination writing in a room in Paris.

When I lived in my literal home island, at each moment the outer British world became part of the deep self creation: my family life, my village, the near town, distant friends . . . (p81)

The island might be Oliver's Englishness which he took everywhere with him as he traveled the world; like a character from Graham Greene who never could quite grasp how slippery everything is. Or maybe he did but chose not to.

Though as a foreign observer I was safe . . . (p95)

The island might be Oliver's place of attack against the choppy waters of literary theory.

The island might be Oliver's archive in the library at the University of Essex.

The island might be Oliver performing his poetry.

It was verray intense . . . (p92)

I don't really believe in stopped time or the instant. My life is more fluid, or liquid. One moment flowing into the next. But then again one time in a pub in St Albans in 1980, and honestly I hadn't been drinking, the whole scene slowed down and the voices went slurred and the faces slipped like a Francis Bacon painting.

If a past memory comes into the present and simultaneously the present is vivid, then the past shares in the immediacy; for a second or two I sense a potential to bring all the intervening life into the immediate as well. (p105)

I come from a bilingual culture; hybridity is my 'natural' state. It is for most people in the world. Others seem to think it affectation or fancy – a kind of willful construct. They believe in the possibility of a stable or essential relationship between language, culture and geography. The popularization of linguistic and literary theory in the 1970s and 80s validated my life experience rather than challenged it. Kind of sad when you think about it.

Unity of form disappears into ambiguous dark whenever we examine it analytically, but its heart is always like the beating heart of a poem: it is the precious origin of our lives' form, or of a true politics. (p107)

The island might be a place of nostalgia, of longing for a certainty that, for some, is only ever a promise.

It could be any moment in any adult life when a past island is left behind; a new one not yet reached. Unfortunately for them, poets often get their work out of such tenseness; they're washing about in a mid-sea . . . (p78)

The island might be a raft made out of the debris that is left after global capitalism has swept through, and the poet a Crusoe figure trying to construct a meaning from the bits and pieces long after capitalism has constructed a number of other possible futures and turns to point and laugh with many empty voices.

And an island might be a place for the avant-garde to hang out mulling over what things might mean while the rest of the world goes scudding past. A kind of post-garde with poor fashion sense, bad haircuts and ethical concerns and endless bickering over definitions and readings in places not designed for readings and picking over the debris of capitalism while capitalism consumes and discards.

In a poem each stress is held in memory and perceived as a unity of sound, meaning and special poetic emotion . . . The stress centres a tiny island in memory. The centre of the island is occluded; it is the moment when we believe the stress actually happened. (p57)

I have never been at home anywhere. Most people haven't. Or if they have they rarely need to bother to write anything down so you won't have heard of them. It's all around them, written in the material of their lives.

Separating from England almost cleaved my unconscious identity in half, an irreparable harm I'd done. (p91)

I live on an island and have done most of my life. The island might be Ynys Mon, or Holyhead Island. As I read I might be constructing an island as a reflection of my own island rather than inhabiting his.

I might be doing him an injustice. This reading might be a misreading.

The island might be a boxing ring. It might be a place of peace or a place of conflict. The boxing ring might be middle class family life in the South of England.

In poemsThe island might be that moment between two events. Like the body of a bird between wing beats. Or it might be the point at which, standing straight up to take your medicine, all defenses are down and the knock out punch gets through.

each beat

fills my mind with melody

half there from the past

half there from the future;

but if the boxer's punch

can catch an opponent

mid-mind

before the self has thought

to fill itself with the self

. . .

any moderately hard punch

at that moment

will K.O. (p62)

The knockout catches the mind between its tiniest islands, in a moment when the instant has not quite entered memory to be filled with form. (p60)

The island might be the:

. . . deep whole healthy self that is constructed of all unconscious vividness built into it . . . (p103)

If he has a deep whole self how does he know it's healthy? Is there no doubt? Maybe in the end we're rotten inside, or some of us are, and all we do is for the wrong reasons. However hard I try to be selfless I end up being selfish. Or is that simply the result of my being ambidextrous, of the left hand never knowing what the right hand is doing. Or classic Gemini tendencies. I think, see, that all the interesting stuff takes place at the edges, just out of sight, stuff I catch out of the corner of my eye. Glances. Glancing blows that keep me rocking. Inside is full to bursting with organs. So the idea of the rays of the object brought to a focus, is replaced by constant blurred movement. No still center. No perfect rest. No possibility of sustaining a position, or an opposition, and a metaphysics of attention is replaced by movement. Movement between countries, on the flickering screen, from lover to lover, from job to job and from poem to poem. Never sitting still and thinking about anything. How to count the loss of that.

I hate authoritative voices. They make me want to spit. Or otherwise misbehave. I don't like the idea of an island but I've chosen to live on one. And it's an island attached to another island. So maybe I like the idea of an island so long as it's in relationship to a lot of other islands. And Oliver almost says that when he says that 'all the islands of ourself expand out to the larger self and the larger self takes place in the great unconscious universe . . .' and my heart goes pitter patter and I reach for the word intertextual or rhizomatic to pin it down and then I read the next bit 'always as itself' and how 'its heart is the precious origin of our lives form'. Islands are the temporarily visible high points of consciousness, arising out of the unity of the unconscious. In the same way that underwater all physical islands are linked by the unity of the world, all 'memory' islands are linked via the unconscious. Each island has its own bordered unity and each person has their own bordered unconscious. It's a tempting visual analogy. It gives a sense of security, and a sense of endless possibility within that security, where all islands are possible in their recombination. But if there are borders to the unconscious, and each conscious island, how can we recognise those borders without consciously crossing them? To recognise the border is to acknowledge the other side and challenge any notion of unity. What is on the other side? Will acknowledging that cause disunity?

An island might be like those islands where strange animals still live cut off from the rest of the world and missed out on mainstream evolution and where words still mean what they say. Why did Oliver go on so much about the similarities and differences of avant-garde and mainstream poetry? Is it because he thought somewhere, through all that, there was an island where he could write the pure poem?

There is no island that is all the world. There isn't. Show me, go on, show me.

-------------

Page references are to 'An Island that is all the World' from the Paladin selection Three Variations on the Theme of Harm.

Comment on Ralph Hawkins' piece--

Peter Riley

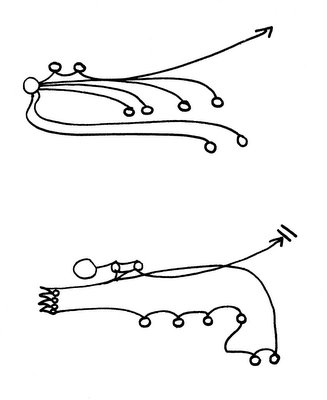

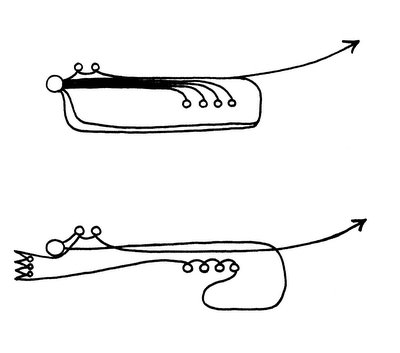

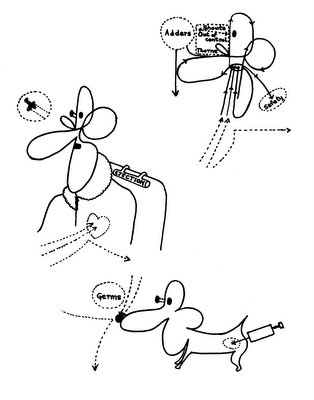

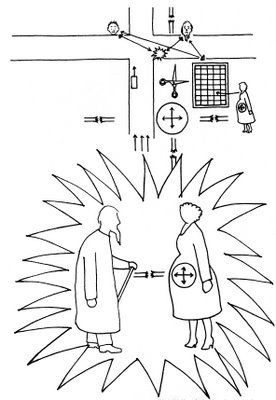

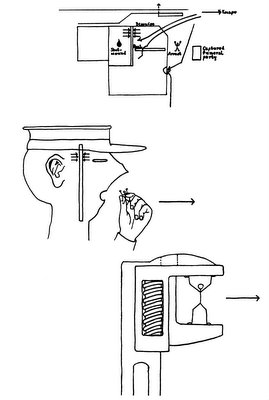

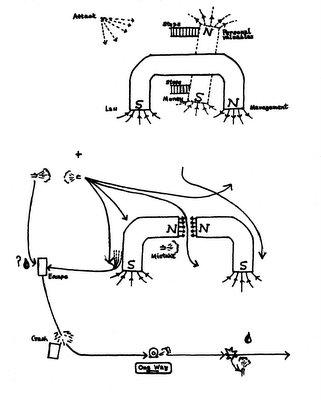

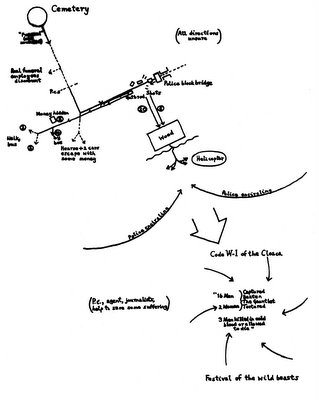

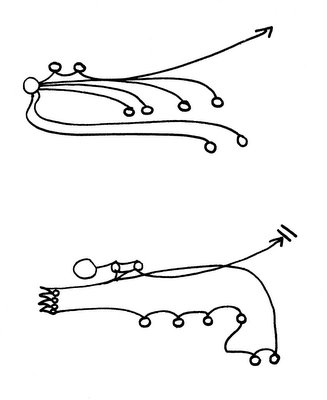

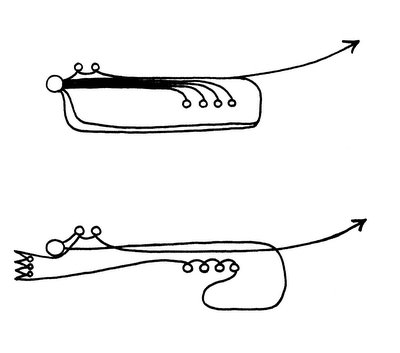

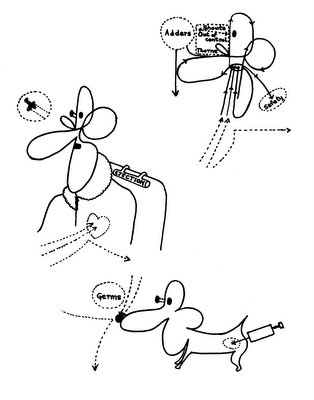

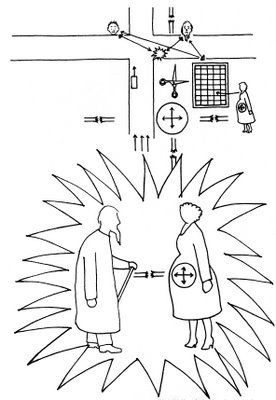

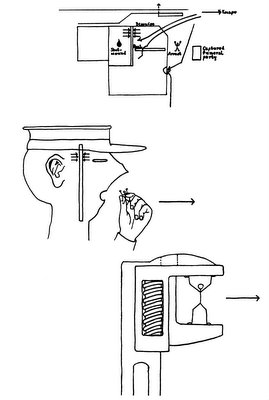

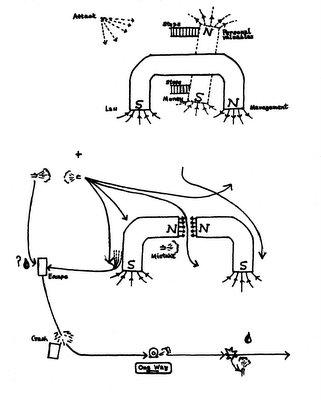

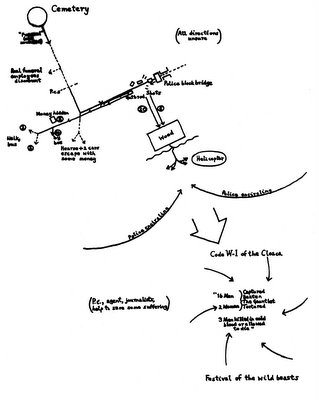

I feel very grateful for this assiduousness. I wonder what difference Ralph thinks the later adventures of the Diagram Poems made? Around 1980 Doug did a lot of readings, almost on tour sometimes, taking with him the diagrams on a huge pad of paper, which he would drape over a chair and flip back the pages from one diagram to the next as he read the poems, with interpolated explanations and comments, mostly on the diagrams -- the poems were read straight. Although much of this was after the Ferry Press publication of 1979 the work was obviously still in process of development, in detail anyway. He says in the Author's Note in Kind (1987) (p.8) "...when performing these in public I have often reverted to my original notion of the text" and that the diagrams have returned to their "more primitive states" before David Chaloner' tidied them.

But in the version in Kind, and more so in Selected Poems (1996) there is a lot more text, a lot more labelling in the diagrams, in fact the amount of labelling increases steadily through the Ochre + 1979 + 1987 + 1996 versions. I take this also to be a result of his performances before an audience, and a wish to reduce the enigmatic, puzzling or inexplicable elements in the diagrams and relate them more evidently to the poems, to reduce the difficulties. For Douglas did believe in clarity as a poetical virtue, clarity of sense and clarity of image, though he often had a struggle to achieve it because of various and conflicting notions of the functioning of poetry which he wanted to assimilate. The diagrams having been meditational sources for elements of the text remain there as indicators of this process, but I don't think Doug wanted them to become visual "works of art" whose semantic inarticulateness spread unnecessary doubts and problems into the ensemble. He may also have been worried about a too meccano-like way of creating poems by taking material from the diagrams into text. The cancelled poem "Do not now always revolve..." (A Meeting for Douglas Oliver p.52) is much more closely related to the diagram than "Fire" which replaced it.

In about 1980 I put on a reading for Doug in a bookshop in Cromford, Derbyshire, at which he did the Diagram Poems. His impromptu comments there went way beyond the occasion. I recorded him on a little cassette-recorder and he later later transcribed this and extended it until it became "The Three Lilies" (1982). In the discussion I suggested to him that The Diagram Poems first really "come alive" in the fourth poem, "Central", when Tom's voice appears, interrupting the news broadcasting and creating a newly dramatic construct. Doug agreed with this, and said he thought it was a structural fault in the book.

Seems to me that Tom also interrupts the diagrams, interrupts the diagrammatic construction of the text and interrupts everything with what Doug in 3 Lilies called vivid emotion. "...vivid emotion conducts us into the gliding instant and a succession of such gliding instants slow down time for us... Poems... give us a presentiment of the gliding and of the visions." So at the point where the book 'comes alive' the movement of the spirit is in the other direction, from text (speech) towards the visual as an arrest of the linear flux. The poem makes its own diagram. I can't help wondering whether that particular diagram (to "Central"), particularly the lower part of it, isn't derived from the poem rather than preceding it.

This slowing or sequential arrest of time in the achieved poem is a weapon against what Doug called "swift harm".

Peter Riley

I feel very grateful for this assiduousness. I wonder what difference Ralph thinks the later adventures of the Diagram Poems made? Around 1980 Doug did a lot of readings, almost on tour sometimes, taking with him the diagrams on a huge pad of paper, which he would drape over a chair and flip back the pages from one diagram to the next as he read the poems, with interpolated explanations and comments, mostly on the diagrams -- the poems were read straight. Although much of this was after the Ferry Press publication of 1979 the work was obviously still in process of development, in detail anyway. He says in the Author's Note in Kind (1987) (p.8) "...when performing these in public I have often reverted to my original notion of the text" and that the diagrams have returned to their "more primitive states" before David Chaloner' tidied them.

But in the version in Kind, and more so in Selected Poems (1996) there is a lot more text, a lot more labelling in the diagrams, in fact the amount of labelling increases steadily through the Ochre + 1979 + 1987 + 1996 versions. I take this also to be a result of his performances before an audience, and a wish to reduce the enigmatic, puzzling or inexplicable elements in the diagrams and relate them more evidently to the poems, to reduce the difficulties. For Douglas did believe in clarity as a poetical virtue, clarity of sense and clarity of image, though he often had a struggle to achieve it because of various and conflicting notions of the functioning of poetry which he wanted to assimilate. The diagrams having been meditational sources for elements of the text remain there as indicators of this process, but I don't think Doug wanted them to become visual "works of art" whose semantic inarticulateness spread unnecessary doubts and problems into the ensemble. He may also have been worried about a too meccano-like way of creating poems by taking material from the diagrams into text. The cancelled poem "Do not now always revolve..." (A Meeting for Douglas Oliver p.52) is much more closely related to the diagram than "Fire" which replaced it.

In about 1980 I put on a reading for Doug in a bookshop in Cromford, Derbyshire, at which he did the Diagram Poems. His impromptu comments there went way beyond the occasion. I recorded him on a little cassette-recorder and he later later transcribed this and extended it until it became "The Three Lilies" (1982). In the discussion I suggested to him that The Diagram Poems first really "come alive" in the fourth poem, "Central", when Tom's voice appears, interrupting the news broadcasting and creating a newly dramatic construct. Doug agreed with this, and said he thought it was a structural fault in the book.

Seems to me that Tom also interrupts the diagrams, interrupts the diagrammatic construction of the text and interrupts everything with what Doug in 3 Lilies called vivid emotion. "...vivid emotion conducts us into the gliding instant and a succession of such gliding instants slow down time for us... Poems... give us a presentiment of the gliding and of the visions." So at the point where the book 'comes alive' the movement of the spirit is in the other direction, from text (speech) towards the visual as an arrest of the linear flux. The poem makes its own diagram. I can't help wondering whether that particular diagram (to "Central"), particularly the lower part of it, isn't derived from the poem rather than preceding it.

This slowing or sequential arrest of time in the achieved poem is a weapon against what Doug called "swift harm".

Peter Riley

A sort of public thank-you to Douglas Oliver

Alan Hay

I imagine Douglas Oliver standing behind me and to the right. Where he in turn imagines the deer standing, and who stands behind the deer? And whenever anyone turns to look it all blinks and disappears. Since my first proper encounter with this singular and compelling man's poetry I've felt myself haunted by his example. Bob Dylan said of Johnny Cash "You could steer your ship by him." I'm in no kind of a boat, Oliver is no constellation, no Orion wheeling across skies of myth and deep time, no Olson, and there in that refusal of the star-crown, handing it always back and back, that ruthless and constant attention to the quivering valencies of justice, to the click of spittle in the human muzzle, tapping the dream barometers, there among the news and mournings and seascapes lie some of the best clues left us as to how we might live, in what world, and who are these poets, how can they help. . .

I first came across Doug Oliver doing a cameo in Iain Sinclair's novel White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings. In an early example of Sinclair's self-ironising (his books recently have been clogged by un-navigable thickets of self-deprecation), Oliver appears, dressed in a long leather coat, to warn Sinclair against meddling with darkness, pointing out the fallaciousness of Eliphas Levi's axiom that it takes a great soul to do great evil. Oliver utters the gnomic injunction to "...fold the bridge, find the cave." The bridge being Sinclair's Suicide Bridge, the cave Oliver's The Cave of Suicession, the real cave in Derbyshire that he nominated as an oracle, crawled into and interrogated about death.

At the time (late 80's) I was a hog for marginalia, liminalia, sweating out a fever stew of post-structuralism and counter-culture occultism, affecting dread in the deep pit of the tory years. Sinclair's formulation of society's engines as malign, hot, in debt to darknesses of the past and somehow printed onto actual urbes as well as civitas, struck me as compelling. I saw Thatcher's Orcs wheeling in the fields of Orgreave, did my pilgrimage to our King Lud, Blake, in Bunhill Fields, the final deferral of whose burial site (his stone says "Near here is buried...") seemed to confirm all my undigested Derrida. Oliver looked to me like a plausible, reasonable post-hippy teacher. Not hot enough, or cool enough.

In these days of print-to-order, abebooks, Salt Publishing, where for the price of a CD you can get everything Tom Raworth ever wrote (well, almost) it's already getting difficult to recall just how tough it was to get hold of material fifteen or more years ago. As a recent graduate, I considered myself pretty au fait. All you had to do, it seemed to me, was hang around in second-hand bookshops, and the stuff you needed virtually levitated off the shelves into your hands. Of course what this actually meant was that I was subsisting almost entirely on Burroughs, Ballard, Ginsberg, what you might call the high-water-mark flotsam of the counterculture. The deeper currents, the stranger stuff, lay outside my view, and may well have done so to this day were it not for the late lamented Compendium Books of Camden. There, like a great confluence of leys, all the hidden tracks broke ground together. The place hummed and crackled with information. I'd gone there on a tip-off looking for Anna Kavan's "Ice" I think (possibly in a leather coat, possibly in sunglasses, shudder...), and was astounded to find that I was in the Library at Alexandria. It was all here. So I bought, and bought. I moved to Islington (when such a thing was still possible for a public sector employee) and spent hours and hours there. And slowly, I began to understand the history that I suspected (paranoia being very much de rigeur) had been actively hidden from me. The first thing to really hit me was Tim Longville and Andrew Crozier's A Various Art anthology. I bought it because I recognised Sinclair's name. And as I sat in the George at the top of Essex Road pissing away my weekday afternoons I became fascinated. Prynne and Peter Riley were my favourites. I don't think I quite got Oliver at that point. The excerpts from "The Diagram Poems" seemed weirdly unbalanced, and the intrusion of the sentimental (to my eye) biographical detail seemed out of kilter with what I took to be the rules of the game. I'd read somewhere that Eric Mottram had described autobiography as 'unsanitary'. I liked this phrase and began to say it a lot, not realising that I was using it as a way of avoiding talking about real people, their histories and actions.

I think I bought Three Variations on the Theme of Harm around then, also from Compendium, and was knocked sideways by two different things. Firstly by "The Infant and the Pearl" which made all my occult political attitudinising seem childishly weak. I stopped it (best I could - still occasional lapses) and tried to follow Oliver's thought through the long poem. Or rather his thinking, its enactment. There was a lot of fuss in later years about Penniless Politics and how it supposedly made possible a new kind of political poetry, but it's all there in Infant. It wittingly placed itself in a tradition of long-form didactic-visionary poetry back through Shelley and Langland to the Pearl poet, but rather than calling on this tradition to underwrite his poem, he makes it earn its keep, forces the alliterative, iterative structure of Pearl to enact the slow, accretive structure of his argument for Socialism. The structure provides a loose and flexible sort of music, but is still sturdy enough to allow this to be readable:

Oliver was an outsider, a mature student, an asker of tough questions at the party. Conscious always of his singularity, his biography seems to strain towards exile - he ventriloquises the Tupamaro guerillas, maps the psychogeography of his Paris arrondissement according to the willed presences of Heine and Celan, leaves England for Paris for England for New York for Paris. That combination of political poetry and outsider power struck a chord with me. I could see that there was a way of making poetry do a real job here. That meaning might, after all, be got from this odd lot.

The second thing that struck me in a slomo combination punch that still rings in my ears was For Kind. This short poem, in metaphysical 'what-is-abstract-quality-x' style has stayed partially digested in my gullet for years. I've never been able properly to parse its deceptively complex structure. Like Beddoes' 'Dream Pedlary' it has the power to stay in the throat and never dissolve. It takes as its perimeter a set of special definitions (kind, kindness, harm, naturalness) whose complex relations cannot be resolved. Its components hang in the air, each vector of referral pointing a Chagall loop round and under - never quite providing enough information to balance the equation, but small enough that you can swallow it whole like an astronaut gulping a zero-g jello-shot. It's what you always knew was the truth about poetry, and an absolute refutation of the new-criticism I'd grown up with, but also a challenge to the crossword-puzzle dessications of some experimental poetry.

So I became a fan. I went back over all the stuff I could find, hummed and hawed over an overpriced (ten pounds!) copy of Oppo Hectic in a bookshop in Greenwich, and tried to find (still haven't) his linguistics / prosody work. I don't say it has been all roses - there's lots we'd disagree about I'm sure. I find his formulation of 'spirit' risky, and there's a little bit of goading of materialists (he breaks cover and does this overtly in Whisper 'Louise') in his resolute insistence on the empirical supernatural. No amount of vague appeals to quantum theory can ameliorate a belief in ghosts, or in phantasms of the living (which belief sunk and brought to suicide the 19th century philosopher and spiritualist Edmund Gurney - no space here to go into this; google it). But every step of the way I knew I was accompanying a real poet. One whose thought was brought right up and out to here through a maze of concentrated attention, of jewel-bright and wax-soft gentleness and strength of moral purpose - that purpose being one of tracking through the maze of wax and mica and forcing speech to make its map and what is that?

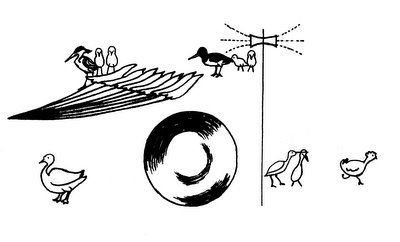

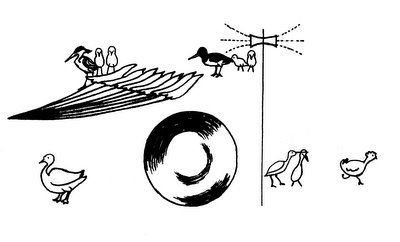

Where does the wing beat begin? Mark the sheer beauty of his conception of the beat, the clairvoyant hinge in the growl and peep of speech, a conception built out of a clear-eyed vision of Sonny Liston peeling time apart in parts of seconds and acting between them, left, left, of the syllabic harmless hum of the all-sanctifying filthy jain, of the heron, grey wing turning time over and over, and the equally beautiful fact of his following this up in the actual laboratory - microphones and charts and all - this alone is a considerable achievement, and a thing of use.

Useful to consider, but difficult to talk about, because Oliver imports all difficulties into his handling of it, feints again and again at the impossible no at the centre, is Tom, Oliver's son, born with Down's Syndrome, and who died horribly young. The death of a child is traditionally the end of the parent. It could certainly do for you as an artist. Think of Samuel Palmer, whose son's death reduces him to vacantly painting again and again the stars in their configuration at the time of death, needle jumping in the trauma groove. (But then think of Mallarme, of Tomb for Anatole.) Is Oliver's conception of his son as a kind of dumb saint (with Kerouackian connotations of holy fool) a little sentimental, dubious in its surrogate piety, a little too close to the special case of private grief to be poetry? But then what would a poetry with no place for a father's grief be worth? And why is the dread trouble of death a special case? Another transmissible insight afforded by these poems is this: an understanding that death needs to be found, that it hides in our lives these days, and the truth about it might be the missing term, and a reminder of what I still find tough to follow: his conviction that ceremony isn't gauche, or anti-materialist, rather it's a kind of physical mnemonic of death.

Oliver pours wine into glasses for dead poets as a fearless rite, makes the challenge to us, and what do we do? Do we pour the wine into an extra glass for Doug Oliver? And do we drink it down? Or pour it on the slabs in the garden and half look away for the deer to come and sniff, touch it with a little pink tongue? Or do we only write it down and never do it? Because when he says, in a heart-freezing moment in the Diagram poems, speaking of bloody revolution and its danger to the defenceless,

Alan Hay, July 2006

I imagine Douglas Oliver standing behind me and to the right. Where he in turn imagines the deer standing, and who stands behind the deer? And whenever anyone turns to look it all blinks and disappears. Since my first proper encounter with this singular and compelling man's poetry I've felt myself haunted by his example. Bob Dylan said of Johnny Cash "You could steer your ship by him." I'm in no kind of a boat, Oliver is no constellation, no Orion wheeling across skies of myth and deep time, no Olson, and there in that refusal of the star-crown, handing it always back and back, that ruthless and constant attention to the quivering valencies of justice, to the click of spittle in the human muzzle, tapping the dream barometers, there among the news and mournings and seascapes lie some of the best clues left us as to how we might live, in what world, and who are these poets, how can they help. . .

I first came across Doug Oliver doing a cameo in Iain Sinclair's novel White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings. In an early example of Sinclair's self-ironising (his books recently have been clogged by un-navigable thickets of self-deprecation), Oliver appears, dressed in a long leather coat, to warn Sinclair against meddling with darkness, pointing out the fallaciousness of Eliphas Levi's axiom that it takes a great soul to do great evil. Oliver utters the gnomic injunction to "...fold the bridge, find the cave." The bridge being Sinclair's Suicide Bridge, the cave Oliver's The Cave of Suicession, the real cave in Derbyshire that he nominated as an oracle, crawled into and interrogated about death.

At the time (late 80's) I was a hog for marginalia, liminalia, sweating out a fever stew of post-structuralism and counter-culture occultism, affecting dread in the deep pit of the tory years. Sinclair's formulation of society's engines as malign, hot, in debt to darknesses of the past and somehow printed onto actual urbes as well as civitas, struck me as compelling. I saw Thatcher's Orcs wheeling in the fields of Orgreave, did my pilgrimage to our King Lud, Blake, in Bunhill Fields, the final deferral of whose burial site (his stone says "Near here is buried...") seemed to confirm all my undigested Derrida. Oliver looked to me like a plausible, reasonable post-hippy teacher. Not hot enough, or cool enough.

In these days of print-to-order, abebooks, Salt Publishing, where for the price of a CD you can get everything Tom Raworth ever wrote (well, almost) it's already getting difficult to recall just how tough it was to get hold of material fifteen or more years ago. As a recent graduate, I considered myself pretty au fait. All you had to do, it seemed to me, was hang around in second-hand bookshops, and the stuff you needed virtually levitated off the shelves into your hands. Of course what this actually meant was that I was subsisting almost entirely on Burroughs, Ballard, Ginsberg, what you might call the high-water-mark flotsam of the counterculture. The deeper currents, the stranger stuff, lay outside my view, and may well have done so to this day were it not for the late lamented Compendium Books of Camden. There, like a great confluence of leys, all the hidden tracks broke ground together. The place hummed and crackled with information. I'd gone there on a tip-off looking for Anna Kavan's "Ice" I think (possibly in a leather coat, possibly in sunglasses, shudder...), and was astounded to find that I was in the Library at Alexandria. It was all here. So I bought, and bought. I moved to Islington (when such a thing was still possible for a public sector employee) and spent hours and hours there. And slowly, I began to understand the history that I suspected (paranoia being very much de rigeur) had been actively hidden from me. The first thing to really hit me was Tim Longville and Andrew Crozier's A Various Art anthology. I bought it because I recognised Sinclair's name. And as I sat in the George at the top of Essex Road pissing away my weekday afternoons I became fascinated. Prynne and Peter Riley were my favourites. I don't think I quite got Oliver at that point. The excerpts from "The Diagram Poems" seemed weirdly unbalanced, and the intrusion of the sentimental (to my eye) biographical detail seemed out of kilter with what I took to be the rules of the game. I'd read somewhere that Eric Mottram had described autobiography as 'unsanitary'. I liked this phrase and began to say it a lot, not realising that I was using it as a way of avoiding talking about real people, their histories and actions.

I think I bought Three Variations on the Theme of Harm around then, also from Compendium, and was knocked sideways by two different things. Firstly by "The Infant and the Pearl" which made all my occult political attitudinising seem childishly weak. I stopped it (best I could - still occasional lapses) and tried to follow Oliver's thought through the long poem. Or rather his thinking, its enactment. There was a lot of fuss in later years about Penniless Politics and how it supposedly made possible a new kind of political poetry, but it's all there in Infant. It wittingly placed itself in a tradition of long-form didactic-visionary poetry back through Shelley and Langland to the Pearl poet, but rather than calling on this tradition to underwrite his poem, he makes it earn its keep, forces the alliterative, iterative structure of Pearl to enact the slow, accretive structure of his argument for Socialism. The structure provides a loose and flexible sort of music, but is still sturdy enough to allow this to be readable:

"...the Second World War for a moment had taughtIn isolation it looks like the kind of All-Bran for the mind that did pass muster in some quarters in the late eighties, but it's half-hidden alliterations and approximate four-stress line give it a feeling of something underneath the level of utterance that links it as a type of knowledge to this:

my nation to know that Conservative negligence

of poverty weakened the purpose fought

for..."

In an interval of fulgurous light, in anAlmost always that first person, declarative tone, full of strong active verb clauses. Very little of the complex and occasionally vague second person plural that so marked a generation of Prynne imitators. Things are busily happening in these poems, and happening to, in and around the poet.

instant when the baby gurgled, all the glass

scythed sideways. I had glimpses of spun

barley-sugar passages studded with sapphires

Oliver was an outsider, a mature student, an asker of tough questions at the party. Conscious always of his singularity, his biography seems to strain towards exile - he ventriloquises the Tupamaro guerillas, maps the psychogeography of his Paris arrondissement according to the willed presences of Heine and Celan, leaves England for Paris for England for New York for Paris. That combination of political poetry and outsider power struck a chord with me. I could see that there was a way of making poetry do a real job here. That meaning might, after all, be got from this odd lot.

The second thing that struck me in a slomo combination punch that still rings in my ears was For Kind. This short poem, in metaphysical 'what-is-abstract-quality-x' style has stayed partially digested in my gullet for years. I've never been able properly to parse its deceptively complex structure. Like Beddoes' 'Dream Pedlary' it has the power to stay in the throat and never dissolve. It takes as its perimeter a set of special definitions (kind, kindness, harm, naturalness) whose complex relations cannot be resolved. Its components hang in the air, each vector of referral pointing a Chagall loop round and under - never quite providing enough information to balance the equation, but small enough that you can swallow it whole like an astronaut gulping a zero-g jello-shot. It's what you always knew was the truth about poetry, and an absolute refutation of the new-criticism I'd grown up with, but also a challenge to the crossword-puzzle dessications of some experimental poetry.

So I became a fan. I went back over all the stuff I could find, hummed and hawed over an overpriced (ten pounds!) copy of Oppo Hectic in a bookshop in Greenwich, and tried to find (still haven't) his linguistics / prosody work. I don't say it has been all roses - there's lots we'd disagree about I'm sure. I find his formulation of 'spirit' risky, and there's a little bit of goading of materialists (he breaks cover and does this overtly in Whisper 'Louise') in his resolute insistence on the empirical supernatural. No amount of vague appeals to quantum theory can ameliorate a belief in ghosts, or in phantasms of the living (which belief sunk and brought to suicide the 19th century philosopher and spiritualist Edmund Gurney - no space here to go into this; google it). But every step of the way I knew I was accompanying a real poet. One whose thought was brought right up and out to here through a maze of concentrated attention, of jewel-bright and wax-soft gentleness and strength of moral purpose - that purpose being one of tracking through the maze of wax and mica and forcing speech to make its map and what is that?

Where does the wing beat begin? Mark the sheer beauty of his conception of the beat, the clairvoyant hinge in the growl and peep of speech, a conception built out of a clear-eyed vision of Sonny Liston peeling time apart in parts of seconds and acting between them, left, left, of the syllabic harmless hum of the all-sanctifying filthy jain, of the heron, grey wing turning time over and over, and the equally beautiful fact of his following this up in the actual laboratory - microphones and charts and all - this alone is a considerable achievement, and a thing of use.

Useful to consider, but difficult to talk about, because Oliver imports all difficulties into his handling of it, feints again and again at the impossible no at the centre, is Tom, Oliver's son, born with Down's Syndrome, and who died horribly young. The death of a child is traditionally the end of the parent. It could certainly do for you as an artist. Think of Samuel Palmer, whose son's death reduces him to vacantly painting again and again the stars in their configuration at the time of death, needle jumping in the trauma groove. (But then think of Mallarme, of Tomb for Anatole.) Is Oliver's conception of his son as a kind of dumb saint (with Kerouackian connotations of holy fool) a little sentimental, dubious in its surrogate piety, a little too close to the special case of private grief to be poetry? But then what would a poetry with no place for a father's grief be worth? And why is the dread trouble of death a special case? Another transmissible insight afforded by these poems is this: an understanding that death needs to be found, that it hides in our lives these days, and the truth about it might be the missing term, and a reminder of what I still find tough to follow: his conviction that ceremony isn't gauche, or anti-materialist, rather it's a kind of physical mnemonic of death.

Oliver pours wine into glasses for dead poets as a fearless rite, makes the challenge to us, and what do we do? Do we pour the wine into an extra glass for Doug Oliver? And do we drink it down? Or pour it on the slabs in the garden and half look away for the deer to come and sniff, touch it with a little pink tongue? Or do we only write it down and never do it? Because when he says, in a heart-freezing moment in the Diagram poems, speaking of bloody revolution and its danger to the defenceless,

"...but my Tom's in a frightener cell..."I still feel my throat close around the indigestible little stone of the poem, grit in the oyster, and know that the place Oliver made there for me to look out from is extremely valuable to me. I use it a lot.

Alan Hay, July 2006

Coincidence and Contraries: Two extracts for Douglas Oliver

Robert Sheppard

1 Ethics

In a letter to Iain Sinclair concerning Sinclair's Suicide Bridge (1979), Douglas Oliver fears that Sinclair's obsession with the Krays, amongst others, is 'yielding creativity into bad vortices', and is tainted with prurience, or sensationalism. (Iain Sinclair: White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings: 159-60) Unlike the earlier Lud Heat (1975), where the patterns of ordinary life counterpoint the grand theories he engages, the constructed mythologies of Suicide Bridge, such as Slade's chilling prophecy, promise nothing but further evil as an inescapable presence within ordinary life. Oliver poses the problem in neo-Blakean terms: 'Can the poetry effect the resolution of good and evil into the coincidence of contraries?' (WCST 160) But the contraries are not ethically neutral, cannot simply balance; Oliver pitches for the 'sovereignty of good', a term of Iris Murdoch's. (WCST 162) Whereas Oliver says that Sinclair's 'phantasms' attempt to prove that 'great evil demands as great a soul as does great good', - a near-quotation from Pascal - Oliver believes evil 'to be small-minded and furious like an atom-power release, and . . . good to expand "in love"'. (WCST 161) Sinclair, writing of the Kray funeral in 1995, in Lights Out for the Territory, recognizes this smallness when he quotes one of the Twins on the murders of George Cornell and Jack the Hat McVitie: 'It's because of them that we got put away,' and comments: 'A nice piece of sophistry – to blame your victims for making you kill them.' (LOT 71) Yet this is the predatory attitude that underlines the universe of Suicide Bridge; it has no room to consider the notion that 'love/moves the sun' as its contrary, Lud Heat, contends (in words which are themselves echoes of Dante's ecstatic incomprehension before the beneficent cosmic order revealed at the end of the Divine Comedy). The doubt for Sinclair, as he observed of JG Ballard's work as late as 1999, is whether, in exposing evil, the writer does not bring about that which he most fears. Oliver also alludes to what the philosopher Hannah Arendt called the banality of evil. One of Sinclair's villain's noted dread of yellow socks hints at the utter lack of sensationalism in real criminal life, but there are few acknowledgements of this in Sinclair's mythic apparatus. Contrast this with the autobiographical account of Tony Lambrianou, scooping Kray victim McVitie's guts up from Blonde Carol's stained carpet to throw them on the fire with a 'little shovel', and one recognizes the banality inherent in that precise detail.

That Oliver's pertinent criticism of Suicide Bridge was published as part of Sinclair's next work, White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings, testifies to Sinclair's generous openness to criticism, and to his prophetic sense that the letter's 'time would come…. The nerve-ends that Doug's letter touched are still twitching'. (WCST 165) And a quarter of century later they still are.

2 Poetics

6th January 2006:

I read Doug Oliver's Whisper 'Louise'. . . He positions his own art as non-mainstream and non 'innovative'. He talks, though, of needing a further dichotomy, that of the extremes of 'clarity' and 'obscurity' - not for his work to be located in the middle (a third way poetics), which is where mediocrity lies, but to inhabit both 'extremes' at once. (He imagines this geopoetically on a map of Paris, Heine and Celan the 'extremes'.) I'm not suggesting for one moment that there is a contradiction here, at all, but that the two go together, at least in Doug's mind.

The work neither belongs to the avant-garde nor to the mainstream; it

belongs to both the extremes of 'positive . . . ballad-like poetry' and

to 'negative opaque and complex' poetry (WL 340)

'both poles . . . are necessary'

the positive is also 'bravery in withstanding vicissitudes';

but is there no 'also' for the negative, no bravery there?

so why that polarity at all?

In any case, a sense here of an individual positioning himself.

The book is also trying to posit the positivities of Poetry: 'A poem taps into poetry, a primordial form of knowing emanating from the "one life" that we share with animals . . . Poetry is a fundamental aspect of mind.' (WL 162). Indeed, more specifically, 'a poem's music models human experience of the passage of time'. (WL 41) (He says also that plot in narrative is the equivalent of music in poetry.) And, less explicitly, but more complexly, poetry is related to an eidetic consciousness, surrounded by the 'humming', the background 'radiation' of the universe. So that:

'In life . . . the healthiest agents of a story's collapse are love, justice, mercy and hope. It takes love to understand' death. (WL 423)

Kind. Kindness. It all ends up as a series of abstract nouns, like Stefan Themerson's 'decency of means' (and indeed both are trying to avoid the fanatic's monomania. . . Philip Roth's I Married a Communist is arguing something similar. Like Oliver, he sees personal heroisms amid both personal and public stupidities (on both sides), the McCarthyite witch hunts not too different a historical mess from the Paris Commune in Oliver's reading.). Yet neither of these is a 'slogan'.

What impresses me is the long-term/large-scale working out of these things. But with the openness to know that he hasn't the answers to some of the things he posits, whether his residual materialist scepticism about 'eidetic consciousness' (which sounds like TM to me), or about the 58 items on his list of 'potentially disastrous pathways' for humanity.

What is interesting is the sense of measuring all this against one's death…. out of some ethic for the only life, the 'one life', the only earth. I think of The Three Ecologies of Guattari – but I remember that he is called a 'bigot' by Oliver in one of the few bigoted moments of the book. . .

This text combines an adapted passage from my monograph Iain Sinclair (Writers and their Work, forthcoming), and a private journal entry.

assembled June 2006

1 Ethics

In a letter to Iain Sinclair concerning Sinclair's Suicide Bridge (1979), Douglas Oliver fears that Sinclair's obsession with the Krays, amongst others, is 'yielding creativity into bad vortices', and is tainted with prurience, or sensationalism. (Iain Sinclair: White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings: 159-60) Unlike the earlier Lud Heat (1975), where the patterns of ordinary life counterpoint the grand theories he engages, the constructed mythologies of Suicide Bridge, such as Slade's chilling prophecy, promise nothing but further evil as an inescapable presence within ordinary life. Oliver poses the problem in neo-Blakean terms: 'Can the poetry effect the resolution of good and evil into the coincidence of contraries?' (WCST 160) But the contraries are not ethically neutral, cannot simply balance; Oliver pitches for the 'sovereignty of good', a term of Iris Murdoch's. (WCST 162) Whereas Oliver says that Sinclair's 'phantasms' attempt to prove that 'great evil demands as great a soul as does great good', - a near-quotation from Pascal - Oliver believes evil 'to be small-minded and furious like an atom-power release, and . . . good to expand "in love"'. (WCST 161) Sinclair, writing of the Kray funeral in 1995, in Lights Out for the Territory, recognizes this smallness when he quotes one of the Twins on the murders of George Cornell and Jack the Hat McVitie: 'It's because of them that we got put away,' and comments: 'A nice piece of sophistry – to blame your victims for making you kill them.' (LOT 71) Yet this is the predatory attitude that underlines the universe of Suicide Bridge; it has no room to consider the notion that 'love/moves the sun' as its contrary, Lud Heat, contends (in words which are themselves echoes of Dante's ecstatic incomprehension before the beneficent cosmic order revealed at the end of the Divine Comedy). The doubt for Sinclair, as he observed of JG Ballard's work as late as 1999, is whether, in exposing evil, the writer does not bring about that which he most fears. Oliver also alludes to what the philosopher Hannah Arendt called the banality of evil. One of Sinclair's villain's noted dread of yellow socks hints at the utter lack of sensationalism in real criminal life, but there are few acknowledgements of this in Sinclair's mythic apparatus. Contrast this with the autobiographical account of Tony Lambrianou, scooping Kray victim McVitie's guts up from Blonde Carol's stained carpet to throw them on the fire with a 'little shovel', and one recognizes the banality inherent in that precise detail.

That Oliver's pertinent criticism of Suicide Bridge was published as part of Sinclair's next work, White Chappell, Scarlet Tracings, testifies to Sinclair's generous openness to criticism, and to his prophetic sense that the letter's 'time would come…. The nerve-ends that Doug's letter touched are still twitching'. (WCST 165) And a quarter of century later they still are.

2 Poetics

6th January 2006:

I read Doug Oliver's Whisper 'Louise'. . . He positions his own art as non-mainstream and non 'innovative'. He talks, though, of needing a further dichotomy, that of the extremes of 'clarity' and 'obscurity' - not for his work to be located in the middle (a third way poetics), which is where mediocrity lies, but to inhabit both 'extremes' at once. (He imagines this geopoetically on a map of Paris, Heine and Celan the 'extremes'.) I'm not suggesting for one moment that there is a contradiction here, at all, but that the two go together, at least in Doug's mind.

The work neither belongs to the avant-garde nor to the mainstream; it

belongs to both the extremes of 'positive . . . ballad-like poetry' and

to 'negative opaque and complex' poetry (WL 340)

'both poles . . . are necessary'

the positive is also 'bravery in withstanding vicissitudes';

but is there no 'also' for the negative, no bravery there?

so why that polarity at all?

In any case, a sense here of an individual positioning himself.

The book is also trying to posit the positivities of Poetry: 'A poem taps into poetry, a primordial form of knowing emanating from the "one life" that we share with animals . . . Poetry is a fundamental aspect of mind.' (WL 162). Indeed, more specifically, 'a poem's music models human experience of the passage of time'. (WL 41) (He says also that plot in narrative is the equivalent of music in poetry.) And, less explicitly, but more complexly, poetry is related to an eidetic consciousness, surrounded by the 'humming', the background 'radiation' of the universe. So that:

'In life . . . the healthiest agents of a story's collapse are love, justice, mercy and hope. It takes love to understand' death. (WL 423)

Kind. Kindness. It all ends up as a series of abstract nouns, like Stefan Themerson's 'decency of means' (and indeed both are trying to avoid the fanatic's monomania. . . Philip Roth's I Married a Communist is arguing something similar. Like Oliver, he sees personal heroisms amid both personal and public stupidities (on both sides), the McCarthyite witch hunts not too different a historical mess from the Paris Commune in Oliver's reading.). Yet neither of these is a 'slogan'.

What impresses me is the long-term/large-scale working out of these things. But with the openness to know that he hasn't the answers to some of the things he posits, whether his residual materialist scepticism about 'eidetic consciousness' (which sounds like TM to me), or about the 58 items on his list of 'potentially disastrous pathways' for humanity.

What is interesting is the sense of measuring all this against one's death…. out of some ethic for the only life, the 'one life', the only earth. I think of The Three Ecologies of Guattari – but I remember that he is called a 'bigot' by Oliver in one of the few bigoted moments of the book. . .

This text combines an adapted passage from my monograph Iain Sinclair (Writers and their Work, forthcoming), and a private journal entry.

assembled June 2006

Reading A Salvo for Africa

Nina Davies

The Cover

The Cover

The back cover of A Salvo for Africa promises something extraordinary from Douglas Oliver:

The way in which I approach this book is shaped by this promise. My assumption is that every page will reflect the complex inequalities in the relationship between Africa and Europe. I also assume that Oliver's poetry will give me a different, more subtle perspective than academic or journalistic writing can achieve. My hope is that the imagination will offer an understanding of the multiple layers of experience lived in relation Africa. Perceptions are formed, through the gaze of film, media, literature, tourism, academia, the internet, museum curators, importers of music and objects, charity organisations and Live Aid/8, long before most Europeans actually set foot on the continent.

Before I open the book, Marcel Mauss whispers the reminder that my concepts of personhood are products of a particular time and space. The notion that I can 'develop' as a person through reading a book seems suddenly ludicrous. Delving into the mind to 'excavate' its concealed patterns and layers, in poor imitation of Freud, seems a symptom of a ridiculous therapy obsessed culture. My own fascination with myself is perverse, especially in relation to Africa. On one level, we are all individuals in culturally shaped boxes rubbing up against each other awkwardly, or shooting each other down across vast divides.

The Poems

It is clear from the first poem that the advantage of this form for describing complex social and political issues is that so much can be condensed and hinted at in a very small space, asking the reader to develop ideas and make connections across time and continents. In Our Family Is Full of Problems Oliver takes the reader on a walk through Coventry and Dar es Salam, explaining the play of history and market forces that has created similar areas of social deprivation in the two cities. However, Oliver is clear that there are differences of scale:

In The Cold Hotel Oliver writes:

Through the Lens

A Woman in Ethiopia and The Infibulation Ceremony are poems written through the device of a lens. The lens acts as a reminder that the western male gaze always objectifies women and in the framing of African women there is a greater removal and increased risk of constructing fantasy. A Woman in Ethiopia is a title we are all familiar with, having watched reels of film of starved women and children in aid camps over the last 25 years. Oliver's poem attempts to show the closeness of a community joined in celebration despite their hunger. He is unable to share their joy because all he can see is starvation and all he feels is shame. The poem is making us conscious of the one dimensional view that poverty and malnutrition is the whole of the Ethiopian experience. Oliver makes us aware that the complexity of social relationships, religion and culture continues even on the edge of survival, which is something that newsreels and aid organisations have little interest in representing. Although bleak images of famine victims may encourage the intervention of western governments and donations to charity organisations, something of our similarities and shared humanity is lost.

The Infibulation Ceremony is a powerful poem, not just for the subject matter, but for the questions it asks about film and who the hell the films are made for and the reasons they are made. Female circumcision is so often used by feminists as an example of the institutionalised violence that women face daily but Oliver's poem is conscious of the fact that this takes place in an environment it cannot hope to understand. However, neither does the poem shirk from the agony of the mutilation:

Memory and Imagination

The question I formulated in reading the cover of A Salvo for Africa was whether poetry could give an alternative perspective to illustrate complexities of Europe's relationship with Africa. There are poems in this book that stretch my imagination and ask me to challenge what I know. One of these is The Borrowed Bow, which sketches an elderly colonial official with a collection of African artefacts who is living out his time in an English coastal town after World War II. A sense of time and place are built with a bakelite wireless and a pier that has been blown up to prevent German invasion. The poem communicates the narrator's boyish fascination with an African bow and the old Wireless, the two objects becoming entwined together in Oliver's memory. Both objects feed the boy's imagination, both are magical and both have the potential to shoot:

The presence of the wireless is a suggestion of the world shrinking through media communication; there is a sense that the signal being picked up is from the home of the bow. I find myself wanting to know when I first heard of Africa. Was it Idi Amin on John Craven's Newsround? Was it Elephants on Blue Peter? I remember Zulu and gun fire. I remember Roots and slavery. Later it was the images of starving children culminating in Live Aid. I remember presenting Evans Pritchard's The Nuer in my first week at University in 1989. I remember my visits to the Pitt Rivers museum in the early 1990's and spending hours pulling out drawer upon drawer of artefacts collected by the early anthropologists in an attempt to 'catalogue' cultures under threat. I remember flying into Malawi in 1999 and being shocked to see only one road cutting across the country, just before my experience of Africa became more than imaginary. Now, when I mention working in Malawi, older people ask what the country used to be called. "Ah, of course, Nyasaland. Hastings Banda," is their response, immediately creating images in my mind of childhoods spent staring at maps of colonial Africa before it crumbled away into the hands of men like Banda. The experience of our different histories holds us apart.

The Borrowed Bow encourages me to both deconstruct my own memory and want to know about how other people understand their experience. It draws a link between all human experience in the forcing together of diverse lives and objects in the space of three stanzas. The title itself can be expanded into a discourse about removing objects from alien cultures and creating exotic fantasies around them which we may then mistake for reality in our construction of the Other. Other poems that work on the same level of memory and imagination are The Childhood Map, Big Game and The Mixed Marriage, which bring together HIV, tourism, Mau Mau, environmental issues, financial markets and international relations into imaginative realms of paper aeroplanes, computer games and displaced objects. For me, these poems are among the most interesting in the book because they demand the complete engagement of the reader. They remind us that Africa has never been a distant place but always present in the next news flash or documentary.

A brief nod at the prose

The poems in A Salvo for Africa are punctuated by prose. Oliver uses this space to cover historical details, introduce his poems or expand on the ideas that they contain. Towards the end of the book he explains his project as an attempt to respond to the complex layers of experience present in real life, criticising the "British poetic culture which sniffs at too much literary ambition" (p 106). A curse of the western way of life is that most of us expect to divorce ourselves from parts of our experience, to the extent that our lives become a practice in specialisation. Oliver reminds us that leaving politics to 'the specialists' is a denial of our individual responsibilities to the world that we have constructed as our Other.

Throughout the book Oliver points with admiration to the African writers who are able to avoid the condescending tone of the West. A Salvo for Africa does not intend to imitate Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Denis Brutus, Frank Chipasula or any other writer who has the experience of growing up on the continent. Oliver's purpose is to make his own culture conscious of itself and allow it to uncover what it already knows about its relationship with Africa. Oliver does not offer answers to these global issues but is constantly pointing in the direction that they could be found. This book refuses to accept that there is nothing we can do and demands that we all face our responsibilities to the present and future populations of the planet.

References

Mauss, M (1985) 'A category of the human mind: the notion of "person"; the notion of "self"', in du Gay, Evans and Redman (eds) Identity: a reader Chapter 26 (2000). Sage.

Spivak, G (1981) 'French Feminism in an International Frame.' In Mary Eagleton, ed., Feminist Literary Criticism, pp. 83-109. Longman Critical Readers. (1991) London & New York: Longman.

The Cover

The CoverThe back cover of A Salvo for Africa promises something extraordinary from Douglas Oliver:

"Fusing political with personal and covering many African countries, his tenth book of poetry invites readers to expose, as he does himself, European viewpoints to a learning process."Can we expect a journey of personal development and insight? Will I learn something about the way in which Africa is 'seen' or 'comprehended' or 'taken in' from the 'outside'? Is it possible to glimpse the processes by which the Other and the exotic are created in society and psyche?

The way in which I approach this book is shaped by this promise. My assumption is that every page will reflect the complex inequalities in the relationship between Africa and Europe. I also assume that Oliver's poetry will give me a different, more subtle perspective than academic or journalistic writing can achieve. My hope is that the imagination will offer an understanding of the multiple layers of experience lived in relation Africa. Perceptions are formed, through the gaze of film, media, literature, tourism, academia, the internet, museum curators, importers of music and objects, charity organisations and Live Aid/8, long before most Europeans actually set foot on the continent.

Before I open the book, Marcel Mauss whispers the reminder that my concepts of personhood are products of a particular time and space. The notion that I can 'develop' as a person through reading a book seems suddenly ludicrous. Delving into the mind to 'excavate' its concealed patterns and layers, in poor imitation of Freud, seems a symptom of a ridiculous therapy obsessed culture. My own fascination with myself is perverse, especially in relation to Africa. On one level, we are all individuals in culturally shaped boxes rubbing up against each other awkwardly, or shooting each other down across vast divides.

The Poems

It is clear from the first poem that the advantage of this form for describing complex social and political issues is that so much can be condensed and hinted at in a very small space, asking the reader to develop ideas and make connections across time and continents. In Our Family Is Full of Problems Oliver takes the reader on a walk through Coventry and Dar es Salam, explaining the play of history and market forces that has created similar areas of social deprivation in the two cities. However, Oliver is clear that there are differences of scale:

And I read a Daily Mail economist forecasting great wealthHere Oliver defines himself as complicit in the systems of inequality that determine Africa's poverty; the poems are conscious of their limitations and inability to offer solutions to the issues they raise. Oliver's talent is to re-present the histories of colonialism and after in a way that reflects the lens backwards onto Europe, reminding us always that we are responsible.

for all free market countries. 'Of course, there will be basket cases,

such as Africa'. And I grab you by the arm.

'Did you hear that? Africa! Not a Coventry suburb, a whole continent

written off in our free trade fanaticism." As if

holding your arm I face towards Africa and write these poems

a representative of a failed British imagination.

In The Cold Hotel Oliver writes:

myself a travelling poet-representativeAgain, he does not separate himself from the rest of us who enjoy a lifestyle sustained by the poverty of others. This drive for luxury and convenience in denial of environmental impact is raised in Soot and the inequality of ownership maintained by the trademark laws is highlighted in Few possessions in Togo. Other poems remind us that European greed in the face of African poverty is an historical 'habit': The King's Garden describes the legal trick that enabled the British colonials to appropriate Bulawayo from King Lobengula's people; A Salvo for Malawi traces the treaties that stole Nyasaland, enslaved its people and then demanded that they fight in World War I for a cause that had nothing to do with their history.

for a people that won't take a dip

in their incomes, no not any

possible good imaginable,

not for the benefit of the future's poor,

not even for their own grandchildren

Through the Lens