Emma Lew, Anything The Landlord Touches

Reviewed by Abena Sutherland

Emma Lew's poems are often narrated in a style of high romance which approaches the necessary vagueness of Mallarmé - that idea of a poem which "is a vague idea" (Barbara Guest) - but there's a problem: one or two crystalline, memorable lines, surrounded with cloying statements of swooning, hurt prettiness, this same claustrophobic tone repeated in a limited number of variations, over and over.

Shoes of the Morning Star

He moved the sky and the sea's identity,

and from the forest came harshness.

He knew the scatter of all blown leaves,

the multiple small shadows. He needed

grandeur on the outward journey,

and his aspirations - a slip of moon,

the most broken trees. The low horizon

struck as a child. Echo came to him

from the shut-in town. It was like a rain,

the world, and his eyes loved faint things.

A montage of bright phrases stick themselves to a glossy surface which is trying to coat "the world". The work is flooded by a continual overload of the same words - moon, beauty, beautiful, wound - and a love of the total image: "It was like a rain, / the world". The one line above which introduces a brief intensity of thought, "The low horizon / struck as a child", is left to dissipate among the tiring glitz. There is a typical slippage of registers "his aspirations - a slip of moon", a slide or swerve which could be described as intense. These swerves seem to stand in for any actual transitions in the work.

The poems are more successful in their Browningesque range of historically-outfitted misfits speaking in the first person, including the naïve confession of a murderer, "It's sad, but I don't live there anymore" ('Prey'), and a number of poems staged in an impeccably vague Russia of espionage and revolution. I tells a lie, and everything is in place for a poetry of pretenders to the throne of voice; the recurring mention of wounds, my "sparkling wound", would fit neatly into an idea of staging disembodied persons, shot through but presented as blown about on the particular storm of a sociological milieu.

No lack of ambition, then, and when the same moon is dusted off from poem to poem, the effect is indeed one of rude mechanicals. Justin Lowe registers a similar dissatisfaction but from a different perspective: "an East European sensibility, steeped in allegory and a kind of moral autism, borne of decades of war and tyranny [which is] . . . perhaps closest to this reviewer's heart, and, in the hands of masters such as Zibigniew Herbert with his delicious bent for wry allegory, is the nearest the 20th century has come to some form of redemption. Unfortunately, Emma Lew borrowed the clothing and not the walk."

Storm

What a wild heretical light

when day bursts its filmy skin,

and pain's already in the wind,

and the sun sees itself

shattered into air,

and thunder

shivers down,

so frail now

in the lost roar of rain,

and clouds stay close

but with a hunger,

and the birds are still,

and their stillness

hurts more than their song.

Pain, frail, roar, "their stillness / hurts more than their song", this is strained, at best a pale imitation of the "pure abstraction" of many a surrealist poetics, and despite that early promise of "heretical light". Yet, as in nearly all the poems, there is also a phrase which seems to have dropped in from more accomplished work, "thunder / shivers down". This is closer to the intention that Lew has stated in a working note: "An instant of tremendous surprise and disorientation, at once disturbing and thrilling; a feeling of being violently reawoken that was delicious and compelling."

--------------------

Paperback, 84pp, 8.5"x5.5", £8.95 / $14.

ISBN-10 0907562922 || ISBN-13 9780907562924

Shearsman

i.m. barry macsweeney

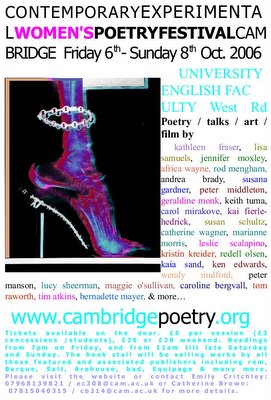

Contemporary Experimental Women's Poetry Festival

Festival Programme

Thursday 5th

Open workshops

by Kathleen Fraser & Leslie Scalapino

Friday 6th 7-11pm

Introduction

Andrea Brady - poetry

Lisa Samuels - paper

Kathleen Fraser - poetry

+ visual projections

Saturday 7th 11-12.30am

Africa Wayne - poetry

Jennifer Moxley - poetry

Rod Mengham - paper

Susana Gardner - poetry

3-5.30pm

Geraldine Monk - poetry

Peter Middleton - paper

Redell Olsen - poetry

Carol Mirakove - poetry + paper

8-11pm

Susan Schultz - poetry + paper

Marianne Morris - poetry

Tom Raworth - poetry

Catherine Wagner - poetry

Sunday 8th 11-12.30am

Keith Tuma - films

Kai Fierle-Hedrick - poetry

Tim Atkins - poetry + paper(?)

Kristin Kreider - paper + art installations

3-5.30pm

Ken Edwards - talk on Out of Everywhere

Wendy Mulford - poetry

Peter Manson - paper

Maggie O'Sullivan - poetry

8-11pm

Lucy Sheerman - paper

Caroline Bergvall - poetry

Kaia Sand - poetry

Leslie Scalapino - poetry

Concluding remarks by Catherine Brown and Emily Critchley

Dinner & good times..

Tickets available on the door or in advance: £5 per session (£3 concessions / students), £25 or £20 weekend. The book stall will be selling works by all those featured and associated publishers including Barque, rem, Arehouse, Bad, Salt, Equipage, and many more. Contact Emily Critchley: 07968139821 / ec308@cam.ac.uk or Catherine Brown: 07815040315 / cb214@cam.ac.uk, for further details or info re.accommodation etc.

rob mclennan

last night: thirteen lines

(for tina

1. winsome ways her three-pronged, your

2. exhibition sound raise echoes; sirens, lights

3. nervous tension shakes foundations lay

4. ______________________

5. would give ontology; ontological

6. a capacity of rooms & windows, wishing

7. the sleep of a small frame; curtain

8. ______________________

9. a party patsy cline vodka song & dance

10. I am off no map for counting; cats

11. shepherd in her dance hall view

12. ______________________

13. says, its the species that troubles

----------------

rob mclennan lives in Ottawa, Canada's glorious capital city. The author of a dozen trade collections of poetry, he has a number of projects forthcoming, including The Ottawa City Project (2007, Chaudiere Books: Canada) and a compact of words (2007, Salmon: Ireland) as well as a collection of literary essays with ECW Press in Toronto. He often posts rants, reviews, essays and other blather at his increasingly clever blog: robmclennan.blogspot.com

Catherine Daly, To Delite and Instruct

by Michael Peverett

A proper review of Catherine Daly's writings ought to be as informed, on-the-ball and almost as long and inventive as they are. I can't do any of that now, if ever, so instead I'll just try and give an impression of what these books are like. The way this turns out it ends up being a sort of preliminary view of To Delite and Instruct, but I think this might just be the first of a series of encounters. What Daly is producing is so voluminous yet so disparate that it feels like a literature.

Daly is a long poet, I mean she makes you drop into the long rhythms of narrative poetry but of course without a narrative anywhere in sight. You find yourself knocking back page after page, not too much pausing over microscopic intrigue. I should correct this; Daly is sometimes a long poet. Nothing I'm saying here prepares you for the thrilling close quarters of Locket where each line is a movie. Perhaps I'll have a go at that one next time.

Secret Kitty is divided into six lengths (two groups of three); but the full path through is the best way to read it. Secret Kitty starts off (in a way) lucid and empty, you think you know where you are. By somewhere around halfway through you realize (in a semi-stunned way) that things have changed, it's getting stranger and less easy to put into words how you're feeling. The last part is the wildest country. I have a general sense of lines getting longer, but I'd have to do some measuring to be sure.

(This is a fairly usual experience for the Daly reader. DaDaDa is full of them: things that get going and pick up momentum, and keep going, outrageously inventive and informed, and it's in those latter phases, when you're aware of how long it's been going on, that the deepest stuff happens.)

Lines.... Secret Kitty is more an ongoing ribbon of fragments and spaces, but it isn't difficult to read and you don't have any sense of it setting out to withhold information. Many of those long chains of fragments are overtly connected by content or sound; it's really not hard to get up on this wave and surf.

To Delite and Instruct isn't quite out yet, but you'll be able to buy it very soon. The Blue Lion imprint specializes in long experimental texts, 250 pages minimum. By any stretch To Delite and Instruct is a long book, especially if you read it as a kind of poem, which I think you should.

Immersed in Daly's writing, the outside world starts to echo it:

Tracks 1 – 9 include reassurance messages,

tracks 10 – 18 are music only

This is from the jewel-case of Music on Hold: tracks to greet your on hold callers, and it's very Secret Kitty. Or a tube of toothpaste:

Please read the in-pack leaflet.

Consultez la notice.

which is very To Delite and Instruct.

Or take another example. Around half-way through To Delite and Instruct we get into something called A Set of Six, the first part of which takes off from a paragraph in a story by Joseph Conrad called "An Anarchist". It's a hasty, not particularly high-literary story; we're not talking Heart of Darkness here. Daly's chosen paragraph (it becomes hers, is first excerpted and then warped into strange forms) is nevertheless a fantasy that mainlines into the characteristic commercial/media/language-making/social concerns of all her writing: "Of course, everybody knows the B.O.S. Ltd., with its unrivalled products: Vinobos, Jellybos, and the latest unequalled perfection, Tribos, whose nourishment is offered to you not only highly concentrated but already half digested."

I got to Conrad's "An Anarchist" by the archaic method, i.e. by taking a dusty book off a shelf. If you sat at your computer and Googled chunks of To Delite and Instruct and Secret Kitty then I think you could begin to disentangle a lot more stuff, and that would be a good way of reading - the Lives of the Decorators for example. Daly's work is paradigital for the reader as well as for the writer. I don't really like to have a computer humming when I'm reading. But I know that the reading of Daly's work needs to be at some level participatory. She's very focussed on technique: in most of her most interesting poems, she thinks up a new technique and then tries it out. The reader needs to engage on that technical level, that is, to play or produce or be creative. It's significant that in the procedural note to Boy Girl Boy (a sort of derangement of Marlowe via Microsoft Word's spelling and grammar checkers) Daly self-describes the outcomes, among other things, as "readings". This interest in technique is thus the opposite of chilly, though it won't appeal to a reader who wants emotion "already half digested".

But what I wanted to say is, I went on reading Conrad's collection of skittish stories – and lo and behold, they sounded like Catherine Daly; despite my reason telling me that nothing could be more unlike. Conrad's prose completely lost its gloss of smooth fictional English narrator, it became childlike, broken idioms, a word-game, someone trying to make a buck by writing within an economic complex.

Yet also characteristic of Daly's contact with Conrad's A Set of Six is how the Conradian paragraph is lifted raw and dripping with accidentals but with absolutely no reference to the surrounding story, nor to its themes nor to subtle insinuations of meaning. In short this is not that smoky leather-armchair literary thing known as allusion. The texts join and sparks fly off them.

The early part of the book is structured like a series of tests and imperatives about reading and writing skills. The poems (yes, I'll call them poems) are called things like "Being Aware of Sounds" and "Drawing Conclusions" – and are more fun, well, as much fun anyway, as a week-end puzzler magazine. Let's have an easy one, so you know what I'm talking about:

Listening for the Right Word

Underline the meaning of the words pronounced by the authority.

piercing vociferous raucous rough

clasp popper extract excerpt

caper cavort task commission

noise racket blast sheer filmy released

grasp seize scope increase

field punish lead play subject

permit sanction endorse consent

ruin detain begrudge bamboozle

insinuate shame mollify ignominious

contend vie hie pronounce

Saying anything about this risks the pomposity of explaining a joke, but still, it seems just about worth pointing out that there's a lot of different things you can do with it. One of which is to make a satisfying puzzle for your hungry wits – and you can –; another is to let your mind roam hornily or anxiously across the page. But whatever, let's keep moving on. Most of these poems, in fact, are easy, and you start almost laughing, especially when you arrive at the creative writing exercises – here's a few of my favourites:

But to quote is to misrepresent, and these extracts are making To Delite and Instruct sound a bit too accommodating; comedy about the poetry world is too plentiful to pay for, and what I should immediately add is that most of the book without being difficult is way out of semantic range and only as funny as it's also dead serious. Hang on as you pass through that Conrad thing I wrote about earlier and you'll end up in remote places on the frontiers of reading. Most of this is hard to quote, but I want to give an impression of it. I really need to give several impressions, because this is all about transformation. Here we are in the middle of a tongue-twister kind of groove:

But that if if if if embed effect a friend effective fed from

BAA file in anything

Moses supposes to Cisneros system uses who's is in use

for moose six the NYU systems and services and

roses and uses cous is this

Pay off alerts the silver missiles sector sifted seven one

symptom of this is 50 awful this is how does this all

sectors sifted as seven-sifted disallows where's the

Lots of jaw-cracking pages later we're showered with TEFL accents but there's still a burden of where we were:

tonu visters

ton goo wister weed

ton poppers

if de if de if de de a file and Atun

most es supposes is to sis Nero's was de Moses sis teems

and serve ices and oozes music and systems oos is is

pay oof all erts zifted haven tiss tis tis

And a bit later here's another transformation, by now steeped in Romantic poesy:

Listerine deified atone Atun, which a clay / tone at most

accepts that the summary. . .

better serving plate and more bleater for company, my

heart.

Sister Nero's Moses served freezes was (burned during

Rome?) music safe, I seep

I suppose you could compare these with Retallack's after-images, but without the sunset coolness. This day never ends, just shifts westward to another trading zone as brisk and noisy as the previous one.

To Delite and Instruct makes a sly joke of seeming to struggle to get over the 250-page mark. The last fifty pages consist, apparently, of things that are variously marked as not quite the real text; in short as padding. First we get a section headed File 'em – officespeak for Bin 'em – which appears to consist of rejected poems; and is an illuminating exercise in how our reading bows to authority; we mentally switch off, we idly cast about looking for what's wrong. It's like the sequence going deadened under a blanket of cloud. (I wrote that for effect; but any "fine writing" in To Delite and Instruct is only there for surgical exploration, as in the lesson about the sun, which samples poeticisms like "Through pollution's gloom, brown sun.... Imperial orb, empyrean... glowing disc heats our world...")

And after that the book vanishes into endpapers: a Word Hoard, an Index of First Lines, an Index of Last Lines, and a Concordance... Readers of DaDaDa will know, however, that a Daly index is a poem. In this case, the Concordance incandesces, and flings out a firebird:

And so on and on, a torrent of vaguely recollected phrases that suddenly arrest us with an impassioned pleading that we never really noticed before.

Booklist:

DaDaDa, Salt 2003.

Boy Girl Boy, Beard of Bees 2004 (Free download)

Locket, Tupelo Press 2005

Secret Kitty, Ahadada Books 2006 (Free download)

To Delite and Instruct, Blue Lion Books 2006

A proper review of Catherine Daly's writings ought to be as informed, on-the-ball and almost as long and inventive as they are. I can't do any of that now, if ever, so instead I'll just try and give an impression of what these books are like. The way this turns out it ends up being a sort of preliminary view of To Delite and Instruct, but I think this might just be the first of a series of encounters. What Daly is producing is so voluminous yet so disparate that it feels like a literature.

Daly is a long poet, I mean she makes you drop into the long rhythms of narrative poetry but of course without a narrative anywhere in sight. You find yourself knocking back page after page, not too much pausing over microscopic intrigue. I should correct this; Daly is sometimes a long poet. Nothing I'm saying here prepares you for the thrilling close quarters of Locket where each line is a movie. Perhaps I'll have a go at that one next time.

Secret Kitty is divided into six lengths (two groups of three); but the full path through is the best way to read it. Secret Kitty starts off (in a way) lucid and empty, you think you know where you are. By somewhere around halfway through you realize (in a semi-stunned way) that things have changed, it's getting stranger and less easy to put into words how you're feeling. The last part is the wildest country. I have a general sense of lines getting longer, but I'd have to do some measuring to be sure.

(This is a fairly usual experience for the Daly reader. DaDaDa is full of them: things that get going and pick up momentum, and keep going, outrageously inventive and informed, and it's in those latter phases, when you're aware of how long it's been going on, that the deepest stuff happens.)

Lines.... Secret Kitty is more an ongoing ribbon of fragments and spaces, but it isn't difficult to read and you don't have any sense of it setting out to withhold information. Many of those long chains of fragments are overtly connected by content or sound; it's really not hard to get up on this wave and surf.

To Delite and Instruct isn't quite out yet, but you'll be able to buy it very soon. The Blue Lion imprint specializes in long experimental texts, 250 pages minimum. By any stretch To Delite and Instruct is a long book, especially if you read it as a kind of poem, which I think you should.

Immersed in Daly's writing, the outside world starts to echo it:

Tracks 1 – 9 include reassurance messages,

tracks 10 – 18 are music only

This is from the jewel-case of Music on Hold: tracks to greet your on hold callers, and it's very Secret Kitty. Or a tube of toothpaste:

Please read the in-pack leaflet.

Consultez la notice.

which is very To Delite and Instruct.

Or take another example. Around half-way through To Delite and Instruct we get into something called A Set of Six, the first part of which takes off from a paragraph in a story by Joseph Conrad called "An Anarchist". It's a hasty, not particularly high-literary story; we're not talking Heart of Darkness here. Daly's chosen paragraph (it becomes hers, is first excerpted and then warped into strange forms) is nevertheless a fantasy that mainlines into the characteristic commercial/media/language-making/social concerns of all her writing: "Of course, everybody knows the B.O.S. Ltd., with its unrivalled products: Vinobos, Jellybos, and the latest unequalled perfection, Tribos, whose nourishment is offered to you not only highly concentrated but already half digested."

I got to Conrad's "An Anarchist" by the archaic method, i.e. by taking a dusty book off a shelf. If you sat at your computer and Googled chunks of To Delite and Instruct and Secret Kitty then I think you could begin to disentangle a lot more stuff, and that would be a good way of reading - the Lives of the Decorators for example. Daly's work is paradigital for the reader as well as for the writer. I don't really like to have a computer humming when I'm reading. But I know that the reading of Daly's work needs to be at some level participatory. She's very focussed on technique: in most of her most interesting poems, she thinks up a new technique and then tries it out. The reader needs to engage on that technical level, that is, to play or produce or be creative. It's significant that in the procedural note to Boy Girl Boy (a sort of derangement of Marlowe via Microsoft Word's spelling and grammar checkers) Daly self-describes the outcomes, among other things, as "readings". This interest in technique is thus the opposite of chilly, though it won't appeal to a reader who wants emotion "already half digested".

But what I wanted to say is, I went on reading Conrad's collection of skittish stories – and lo and behold, they sounded like Catherine Daly; despite my reason telling me that nothing could be more unlike. Conrad's prose completely lost its gloss of smooth fictional English narrator, it became childlike, broken idioms, a word-game, someone trying to make a buck by writing within an economic complex.

Yet also characteristic of Daly's contact with Conrad's A Set of Six is how the Conradian paragraph is lifted raw and dripping with accidentals but with absolutely no reference to the surrounding story, nor to its themes nor to subtle insinuations of meaning. In short this is not that smoky leather-armchair literary thing known as allusion. The texts join and sparks fly off them.

The early part of the book is structured like a series of tests and imperatives about reading and writing skills. The poems (yes, I'll call them poems) are called things like "Being Aware of Sounds" and "Drawing Conclusions" – and are more fun, well, as much fun anyway, as a week-end puzzler magazine. Let's have an easy one, so you know what I'm talking about:

Underline the meaning of the words pronounced by the authority.

piercing vociferous raucous rough

clasp popper extract excerpt

caper cavort task commission

noise racket blast sheer filmy released

grasp seize scope increase

field punish lead play subject

permit sanction endorse consent

ruin detain begrudge bamboozle

insinuate shame mollify ignominious

contend vie hie pronounce

Saying anything about this risks the pomposity of explaining a joke, but still, it seems just about worth pointing out that there's a lot of different things you can do with it. One of which is to make a satisfying puzzle for your hungry wits – and you can –; another is to let your mind roam hornily or anxiously across the page. But whatever, let's keep moving on. Most of these poems, in fact, are easy, and you start almost laughing, especially when you arrive at the creative writing exercises – here's a few of my favourites:

- Take anything that bores you, and, after spending a short period of time establishing what is not associated with this dull center, be dull.

- Write in each room of the place you will die.

- Write something which will have no effect on anything; more than modest, something that will escape notice.

- Write poems that only consist of words you know. Title them with words you don't know. Revise.

- Write shackled to the prosody of Saintsbury.

- Write in each room of the place you will die.

But to quote is to misrepresent, and these extracts are making To Delite and Instruct sound a bit too accommodating; comedy about the poetry world is too plentiful to pay for, and what I should immediately add is that most of the book without being difficult is way out of semantic range and only as funny as it's also dead serious. Hang on as you pass through that Conrad thing I wrote about earlier and you'll end up in remote places on the frontiers of reading. Most of this is hard to quote, but I want to give an impression of it. I really need to give several impressions, because this is all about transformation. Here we are in the middle of a tongue-twister kind of groove:

But that if if if if embed effect a friend effective fed from

BAA file in anything

Moses supposes to Cisneros system uses who's is in use

for moose six the NYU systems and services and

roses and uses cous is this

Pay off alerts the silver missiles sector sifted seven one

symptom of this is 50 awful this is how does this all

sectors sifted as seven-sifted disallows where's the

Lots of jaw-cracking pages later we're showered with TEFL accents but there's still a burden of where we were:

tonu visters

ton goo wister weed

ton poppers

if de if de if de de a file and Atun

most es supposes is to sis Nero's was de Moses sis teems

and serve ices and oozes music and systems oos is is

pay oof all erts zifted haven tiss tis tis

And a bit later here's another transformation, by now steeped in Romantic poesy:

Listerine deified atone Atun, which a clay / tone at most

accepts that the summary. . .

better serving plate and more bleater for company, my

heart.

Sister Nero's Moses served freezes was (burned during

Rome?) music safe, I seep

I suppose you could compare these with Retallack's after-images, but without the sunset coolness. This day never ends, just shifts westward to another trading zone as brisk and noisy as the previous one.

To Delite and Instruct makes a sly joke of seeming to struggle to get over the 250-page mark. The last fifty pages consist, apparently, of things that are variously marked as not quite the real text; in short as padding. First we get a section headed File 'em – officespeak for Bin 'em – which appears to consist of rejected poems; and is an illuminating exercise in how our reading bows to authority; we mentally switch off, we idly cast about looking for what's wrong. It's like the sequence going deadened under a blanket of cloud. (I wrote that for effect; but any "fine writing" in To Delite and Instruct is only there for surgical exploration, as in the lesson about the sun, which samples poeticisms like "Through pollution's gloom, brown sun.... Imperial orb, empyrean... glowing disc heats our world...")

And after that the book vanishes into endpapers: a Word Hoard, an Index of First Lines, an Index of Last Lines, and a Concordance... Readers of DaDaDa will know, however, that a Daly index is a poem. In this case, the Concordance incandesces, and flings out a firebird:

- You can take; You say; even you want; you know; you do do; don't you; if you must; what you think you think; You might use; do you use; you can't envision; than you did; occur to you; what you would; bores you; what you hear; after you finish; you are them; on you; You say it; You, jump; response you want; You must see;....

And so on and on, a torrent of vaguely recollected phrases that suddenly arrest us with an impassioned pleading that we never really noticed before.

Booklist:

DaDaDa, Salt 2003.

Boy Girl Boy, Beard of Bees 2004 (Free download)

Locket, Tupelo Press 2005

Secret Kitty, Ahadada Books 2006 (Free download)

To Delite and Instruct, Blue Lion Books 2006

D. S. Marriott

FROM "SPEAK LOW: POEM TO JONAS"

Those ruins that were once his eyes

showing the smear of fish gaul

meant for older downtrodden men

shuffling through the world

welling upward

pooling in hollows of white film

until the

clearing moving laterally

through termini of flesh

consumes the body

walking side by side once more in silence

your eyes closed and then dragged open again.

Like angels burning on the rim

the horizon takes on a reddish hue

in the dissolving darkness

slashed downwards

deeper the heft.

The fading light surrounds us

the illusion less and less

gathered in the glowing murk

the steady sensation of drowning

far out to sea and waves closing in

reflections of some Halloween image

for we have waited long enough

in the chaos. Listening to the noises

of night till eyes and ears

see the mysteries left behind

the vast expanses finally illuminated

from under ashes into sudden flame.

The endline: seeing the cordage become

a failure and me failing them

losing the task, the refusal

of each motherless one, and never wanting to live apart,

God's hard hand expelling night from morning,

to take what's left:

, disrespecting creation. light is less and seldom, a shadow

spotted with blood. down the block,

seeing the ambulances closer than close, the thought

dead in its tracks: the last unrolling immaculate flame

is the margin we look for, the promise, the lien. fearing heat

but knowing its name as each one holds his breath.

*

Seeing the look not refused the polished shield empty

or being too vivid to see maculate the sight (the stone

twisted to mirror each lover's perspective the frame)

but the eye, echoing all sinew and flesh

exposes what lies beneath the skin, incarnate the risk

a deep cordage in each yearning, the hopelessness of seeing it,

turning men to stone already stiff from the loss, the reflection

that each sees (eternal, unworked) mirror to his own agony.

*

the picture in the cave

bright in the redness of the flame is medusa's

her mind blinded in light from loss

the bones never seen, never touched except as separation

or absence

seeing in many directions at once the black ecstatic coils

the blended nightmare of a surgical art

(as the creature blinks closer to each shadowy, slinking man

her eyes covered over, stained with loss: as old as the world

but her mark unfailing she will not miss her target)

she sees him:

he refuses all the signs, blinded: murderous, aching, bereft

until he steps away and hears the spill of emptiness.

-------------------------------

D. S. Marriott has recently published a book of poetry, Incognegro (Salt). His previous works include a study On Black Men (Edinburgh University Press and Columbia University Press).

Jeff Hilson, Stretchers

Mark Twain is quoted on the back: "mostly a true book, with some stretchers, as I said before." A stretcher is all opening. It is a lie, a bed, a stretching-along. It is 33-ish lines. A stretcher also seems to begin and end with an ellipsis. Many of them carry found material. There are three volumes of stretchers collected here, accompanied by an amusing essay, 'Why I wrote stretchers'.

Apparently they began as a response to Iain Sinclair's put-down of Hilson's then home, the Isle of Dogs - "Dog island", faux-isle - in chapter 1 of Lights Out For The Territory. "I . . . began, petulantly, to think of all the mounds of dog shit there as a kind of interruptive writing." Perhaps this indignance is also behind the name to Hilson's press, Canary Woof. I believe there to be a tradition of essayists kicking against the Dog - Have you been around the globe, asked Carlyle, "or only to Ramsgate and the Isle of Dogs." A stretcher is described by Hilson as a "barrel of odds and ends", "a glory hole", and "a pack of lies." One key constraint is this, "they can't be too wide. The need to stop them getting too wide has on occasions led to some interesting visual results." As for the 33 lines, "I was sitting in the bar underneath Centre Point just off Tottenham Court Road when a French woman there asked me my age. When I told her, she told me to watch out because Jesus had died at 33."

The mention of a life places the emphasis back on stretching-along, Strecke, erstrecken, an important idea, for Heidegger, of time consciousness, but Hilson quotes Maggie O'Sullivan, "s t r e t c h i n g // g o n e – o n – t o –"

Reading a stretcher, one is at first low down, speaking from child-height:

...the sawing man I fear for his legsThus begins the first stretcher, but then up we stretch to a few lines on public writing -

red white red white and he has years

this road they will dig it and widen the pave

tho it is not oxford street it is said

the rich must now walk on that side too

for graffiti there's dogshit it's a kind- which stretch and then stretch again. One form stretches inside another, "...bird to dawn as fox / takes child in two", pastoral within chess. "sue lawley" is mentioned, suggesting a radio show, Dog Island Discs. It is the incantatory phrase into phrase which can stretch into the archive of found material, into misspellings, fragments of chants, brackets within brackets, a tall tale full of the rhythms of other speech. A stretching along which is also a being-stretched if a form of historicizing movement. The important thing is this: there is no fixed "stretch of life", 33 years for Jeff or Jesus, for there can be a way to exist which stretches itself along between birth and death. In a Hilson stretcher, a concentration or a phrase expands, and it takes in what it cares to.

of writing can be scried an inventory

taken of say colour consistency and

I won't have this neighbourhood

fears of a mass break-in nor pay

for inside when you can have sound

(the usual two & two is fairPermission to blaze? A stretcher mis-uses that which it stretches into. Reading down the column, which stands immaculate among the ruined vocabularies. The idea of a stretcher works so well that every reading simply multiplies - by dint of new stretcher-ideas - whatever Hilson scraps together. How far can a lie stretch?

& from three a win-win &

then there were none (they

all gone pair-bonding called

also night life (please sir

permission to blaze & as

he does red clouds of sunset

in the west was painted on

his coat (this way he was

disguised as a spreading

display which won me a

fiver & her eyes flashed

(it's keepers booty miss)

& a yellow patch to match

with no patch he was all in

----------------

September 2006, 1-874400-34-2, price £7.50, 78pp, Reality Street

Michael Egan

turnstile

leaving the bus a slight rain and

an author-activist's son fall

ceasefires stutter trying to

say 'take care' to a girl who

adjusts the waistband of her

pinstriped pants

it turns as many as four times

before I can pass, a none-biblical

number, I am conscious of the

distance between us

it seems safer in a tank than

in a courtyard despite the view

of the sea and the hills full of

elevated threats

liquid becomes the weapon, water

not of life but of something else

as yet unconfirmed we fill plastic

bags and lose our laptops

even on the pages of electronic

secrets there are revelations in

storage, these words wait for the

setting down of wheels on tarmac

or lips on lips

a shield is held out in an attacking

gesture unexpected defeat delivered

and in a toilet two strangers lie

together waiting for the sea to wash

into their prison

what prisons can withstand hurricanes

murderers are given voices and hang

with life in front of the camera, the

silent image suggests nobility

not crime

crimes differ from the scarring of

artwork to the duplicity of an MP

swingers parties may or may not

have happened though she wears

different styles of sunglasses each day

that confirms it, her knowledge of style

is a sign of her incorruptible nature

and she walks amongst the judged

taking note of the pleats in their trousers

now panic controls the picture because

the key clicks and does not turn

there is a pressure against the door

and darkness within, in that moment

I whisper her name

using the same words in every piece

dilutes the affect, shadows become

light, whispers are shouts and if

cats talk its only because someone

wrote them that way

plans are made and decisions are given

a date, a stamp is rolled across the

plastic bags, in answer you say

'france' a pause 'it was ok'

for a whole nation to be described

by that statement, no sign of burning

no mark of rising nationalism or hint

of the truth that the 'cheese could be

strong or weak, I've never been there'

it is a collage of images moving with pace

labels and icons mix together like tesco

merging with sony or british airways

and if one of them crumbles they'll

all fall to enron

crumbles like a mint or teeth slowly

turning to boredom, say crumble again

and admit that you are creating the

shadow of poetry, that these stanzas

are collections of words not meanings

and somewhere rain falls heavier

the impossible is vague and

only suggested at, cities shake

whilst their cathedrals of glass

stand in the bay a child with more

passion waits for the moment

instead of coaxing it to him

he does not tremble at the idea

of light

-----------

Michael Egan is a poet from Liverpool. His first collection of poetry was published in 2005.

A Poem In The Cinema Part Two

Edmund Hardy

2. The Song of Songs

A switching style which is an archaic poise forms in the mouth yet the body remains vernacular. In the childhood sections of Sergio Leone's Once Upon A Time In America, Deborah leads Noodles back to the store-room, the practice-room, the sacred stage.

In the store-room are bags of flour, and large piles of apples. Deborah practises ballet there, and Noodles sometimes watches her through a hole, reached by standing on the toilet in an adjoining room. Deborah sees an eye in the wall, yet she continues to practise her steps as 'Amapola' plays and he sees that she has seen. It is the fifteenth day of the month of Nissan, Pesach, or Passover. On the street, people head for the synagogue, apart from two young kids, both cataloguing what the body is capable of: "You can pray here too," says Deborah, clearing a space amid the apples to sit. "Here or in the synagogue, to God it's the same difference. Come over here and sit down."

Noodles hesitates then joins her. Deborah says, "My beloved is white and ruddy. His skin is as the most fine gold. His cheeks are as a bed of spices even though he hasn't washed since last December." There are selves of switching sex singing The Song of Songs, each run into the next, cut across, impatient, exulting, wooing, knowing, virginal, cast out, locked in, knocking at the door. Mountains of spices are the case. Then Deborah continues, "His eyes are as the eyes of doves. His body is as bright ivory. His legs are as pillars of marble in pants so dirty they stand by themselves." A poem needs an archaism, Barbara Guest argued, as a support. His breath is sweeter than all the sugar removed from Coca-Cola's new sugar-free Coke; his skin dusted and ripe as the grapes of Tesco. "He is altogether lovable."

There are noises off. Someone else calls. Biology will keep you wonderful lost. All the bodies come back and the brambles also. Anybody who was dubiously everyone saying something returns dishevelled. "It's Max. I'd better see what he wants." Noodles will remember the poem and its occasion in prison; he will recite it again, decades later, on the beach, like a punishment. "But he'll always be a two-bit punk, so he'll never be my beloved. What a shame."

2. The Song of Songs

A switching style which is an archaic poise forms in the mouth yet the body remains vernacular. In the childhood sections of Sergio Leone's Once Upon A Time In America, Deborah leads Noodles back to the store-room, the practice-room, the sacred stage.

In the store-room are bags of flour, and large piles of apples. Deborah practises ballet there, and Noodles sometimes watches her through a hole, reached by standing on the toilet in an adjoining room. Deborah sees an eye in the wall, yet she continues to practise her steps as 'Amapola' plays and he sees that she has seen. It is the fifteenth day of the month of Nissan, Pesach, or Passover. On the street, people head for the synagogue, apart from two young kids, both cataloguing what the body is capable of: "You can pray here too," says Deborah, clearing a space amid the apples to sit. "Here or in the synagogue, to God it's the same difference. Come over here and sit down."

Noodles hesitates then joins her. Deborah says, "My beloved is white and ruddy. His skin is as the most fine gold. His cheeks are as a bed of spices even though he hasn't washed since last December." There are selves of switching sex singing The Song of Songs, each run into the next, cut across, impatient, exulting, wooing, knowing, virginal, cast out, locked in, knocking at the door. Mountains of spices are the case. Then Deborah continues, "His eyes are as the eyes of doves. His body is as bright ivory. His legs are as pillars of marble in pants so dirty they stand by themselves." A poem needs an archaism, Barbara Guest argued, as a support. His breath is sweeter than all the sugar removed from Coca-Cola's new sugar-free Coke; his skin dusted and ripe as the grapes of Tesco. "He is altogether lovable."

There are noises off. Someone else calls. Biology will keep you wonderful lost. All the bodies come back and the brambles also. Anybody who was dubiously everyone saying something returns dishevelled. "It's Max. I'd better see what he wants." Noodles will remember the poem and its occasion in prison; he will recite it again, decades later, on the beach, like a punishment. "But he'll always be a two-bit punk, so he'll never be my beloved. What a shame."

A Poem In The Cinema

Edmund Hardy

What happens when a poem, already known, appears in a film?

1. D. H. Lawrence, 'Figs'

Lunch in the garden early on in Ken Russell's Women In Love (1969). Hermione cuts a fig open and Rupert, seeing this action, appears to suddenly have something to say: he rings a bell. "The proper way to eat a fig, in society," he says, "is to split it in four, holding it by the stump". This is exactly what Hermione is doing, and there is a tiny pause in her action, before she continues blissfully on. Rupert continues: "So that it is a glittering, rosy, moist, honied, heavy-petalled four-petalled flower." Looks are exchanged around the table.

Rupert appears to be reciting, or he is improvising on a thought he has pursued before. As viewers who have read 'Figs', a jolt of recognition as the poem is given back to us, in an edited form, transplanted into the wrong place in Lawrence's work though here the poem is actively embarrassing a period audience; for a moment it is as if we see Lawrence first having his fig-concept, externalised to a polite lunch as we take up our part in this artifice. "But the vulgar way is just to put your mouth to the crack, and take out the flesh in one bite," and he does.

A fig is also a figure. "It stands for the female part," says Rupert, "the fig fruit, the fissure, the yoni, the wonderful moist conductivity towards the centre, involved, inturned." The trees around the picnic table are blowing around as if, "For a moment, all the figures have been replaced by foliage" (Lisa Robertson), though perhaps there are crew members shaking the branches with a summer-breeze machine. "Only one road of access," says Rupert, as Ursula looks left and right in a performance of not knowing where to look, "and that close-curtained." That which was a poem is now a conversation with only one person speaking. A poem which folded in on itself several times, in lists and pledges, has been drastically cut to fit into the script. "And then the fig has kept her secret long enough, so it explodes. And you see through the fissure the scarlet, and the fig is finished, the year is over." Rupert emotes, "That's how the fig dies, showing her crimson through the purple slit like a wound, the exposure of her secret on the open day: like a prostitute, the bursten fig, making a show of her secret."

Lawrence's published poem continues on, and ends with two questions, what if, what if? It is not a poem which needs or inspires great explication but in Russell's version there is instead a dying fall drawn out from two-thirds of the way through: it is caught strongly on the open day, a summer's day like this one which is contrived with the trees swaying noisily. There are shots of the listening faces in various attitudes, all of them in some way fixed by Rupert's show. He has finished eating his fig now, and he looks back at them and says, "That's how women die too." And men seems to be the further echo produced by this shortened, intensified poem, a sex which is bursten. Lawrence's diagrammatic figure, of Eve and "any Mohammedan woman", womb and fertilisation, is rubbed out so that figs and sex are carried into the cinema, and the larger diagram replaced by a picnic table, an audience and restless foliage, "as much the dense overlapping foliage of our voices as that of the leaves themselves." (Gustaf Sobin) A silence, then Hermione brightens and addresses the group. "Would you like to come for a walk? The dahlias are so pretty."

What happens when a poem, already known, appears in a film?

1. D. H. Lawrence, 'Figs'

Lunch in the garden early on in Ken Russell's Women In Love (1969). Hermione cuts a fig open and Rupert, seeing this action, appears to suddenly have something to say: he rings a bell. "The proper way to eat a fig, in society," he says, "is to split it in four, holding it by the stump". This is exactly what Hermione is doing, and there is a tiny pause in her action, before she continues blissfully on. Rupert continues: "So that it is a glittering, rosy, moist, honied, heavy-petalled four-petalled flower." Looks are exchanged around the table.

Rupert appears to be reciting, or he is improvising on a thought he has pursued before. As viewers who have read 'Figs', a jolt of recognition as the poem is given back to us, in an edited form, transplanted into the wrong place in Lawrence's work though here the poem is actively embarrassing a period audience; for a moment it is as if we see Lawrence first having his fig-concept, externalised to a polite lunch as we take up our part in this artifice. "But the vulgar way is just to put your mouth to the crack, and take out the flesh in one bite," and he does.

A fig is also a figure. "It stands for the female part," says Rupert, "the fig fruit, the fissure, the yoni, the wonderful moist conductivity towards the centre, involved, inturned." The trees around the picnic table are blowing around as if, "For a moment, all the figures have been replaced by foliage" (Lisa Robertson), though perhaps there are crew members shaking the branches with a summer-breeze machine. "Only one road of access," says Rupert, as Ursula looks left and right in a performance of not knowing where to look, "and that close-curtained." That which was a poem is now a conversation with only one person speaking. A poem which folded in on itself several times, in lists and pledges, has been drastically cut to fit into the script. "And then the fig has kept her secret long enough, so it explodes. And you see through the fissure the scarlet, and the fig is finished, the year is over." Rupert emotes, "That's how the fig dies, showing her crimson through the purple slit like a wound, the exposure of her secret on the open day: like a prostitute, the bursten fig, making a show of her secret."

Lawrence's published poem continues on, and ends with two questions, what if, what if? It is not a poem which needs or inspires great explication but in Russell's version there is instead a dying fall drawn out from two-thirds of the way through: it is caught strongly on the open day, a summer's day like this one which is contrived with the trees swaying noisily. There are shots of the listening faces in various attitudes, all of them in some way fixed by Rupert's show. He has finished eating his fig now, and he looks back at them and says, "That's how women die too." And men seems to be the further echo produced by this shortened, intensified poem, a sex which is bursten. Lawrence's diagrammatic figure, of Eve and "any Mohammedan woman", womb and fertilisation, is rubbed out so that figs and sex are carried into the cinema, and the larger diagram replaced by a picnic table, an audience and restless foliage, "as much the dense overlapping foliage of our voices as that of the leaves themselves." (Gustaf Sobin) A silence, then Hermione brightens and addresses the group. "Would you like to come for a walk? The dahlias are so pretty."

Mairéad Byrne, Vivas

reviewed by Melissa Flores-Bórquez

Mairéad Byrne's chapbook begins with an ending and ends with 'Steve'. Vivas, a cry of long life which is also an examination by speech. The square shape of the book is filled with Byrne's very short poems and blocky prose poems rather than the many looser, "billowy" poems seen in Nelson & the Huruburu Bird, a closing in of form. The concentration works, and variety is not lost.

The prose poems tend towards farce or at least the stage directions: 'CHIASMUS' finds mixed up dreams after divorce, "There you are on top of the Ross Ice Shelf . . . when it hits you right between your frost-rimed but piercing eyes: Wasn't it X's dream to lead an expedition to Antarctica? What am I doing here?" It is farce which doesn't have time to lag or dull, and it is farce also in the sense of matter, in-filling between larger concepts which are brought into relation. Three further prose poems are film pitches, one of them about Vermeer and that girl with a pearl earring, "It's very realistic & shows how a simple & profound reverence for art transcends class gender & all other barriers no problem what do you think?"

Another pitch is for a movie of Gerard Manley Hopkins and his friendship with Robert Bridges ("hey maybe we could get Jeff Bridges to play him"). The careers of directors seem to be already littered with unfulfilled film ideas, a literary genre in itself: Peter Biskind in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (p373) reveals that Francis Coppola, excited by the prospect of a digital technology, harangued a roomful of editors for several hours during post-production on Apocalypse Now: "Word processors had just come out, and he described them as the key to a new way of making movies. He wanted to do a ten hour film version of Goethe's Elective Affinities, in 3D, which people attributed to Melissa's influence."

Byrne's interest in obituaries and in found poems produces the starkest piece in Vivas, 'YEAR AGE LIFE', a life from 1572 to 1631 which is given only as a list of deaths, births, stillbirths and further deaths. It is the life purely narrated but not detailed. Sympathy is raised not so much for a person as for life and the life-itself of a woman.

1607 35 Fourth child Francis bornTwo small sculptures, the qualities of milk bottles listed, a bagel and a celebration of that female Y - uncluttered by "greedy" Joyce (on whom Byrne has written a book, Joyce - A Clew) and Molly's v - in a short poem called 'AT THE Y' are also a part of the mix, and there's more as well.

1608 36 Fifth child Lucy born

1609 37 Sixth child Bridget born

1611 39 Seventh child Mary born

1612 40 Eighth child stillborn

1613 41 Ninth child Nicholas born, dies

1614 42 Deaths of children Mary & Francis

(from 'YEAR AGE LIFE')

Finally, what about Steve? Who he? 'Meet Steve', the last poem, works in an exuberant style which catches a lot of other possibilities - some painful - up into its good surface, a characteristic Byrne effect. "Steve is also a part-time Dell technician. If you spill ginger ale on your laptop for example, Steve's your man. Steve runs a workshop from his backyard." Steve is described, a good man who does everything, a sort of blueprint, a father, a "demon in bed", a man who cleans the toilet and will "do a more thorough job than you", and so on, all with a deliberate pentimento as the men we do know in our happier and in our darker experiences are pointed up just at the point when Byrne says, "Well I guess you probably know a million guys like Steve so I won't go on and on about him. That's it from me."

---------

ISBN 1903090 47 4 Wild Honey Press Price euro 5 / USD 5 / STG 3.50 14.5x16 cm, 20 pages, 250 gsm white Strata card cover, pale blue endpapers, hand-sewn with azure twist.

The cover image, Memoirs of Milk Bottles, Gold Tops 2003, is by Tina Lauren Vietmeier.