Ian Davidson, No Way Back

West House Books (Gargoyle Editions) / Price £1.50 / 5pp / Loose leaf pamphlet

Also published at Ian Davidson's Archive of the Now page

Reviewed by Laura Steele

--------------------------------------------

This Ian Davidson poem is a filter of statements – external seascape, internal series of questions on "politics", external internalised and beginning to figure as speech, "begin to say something" – across which "the heart sings discordant".

The sea drags shingle

over and over the stone in

heaps of stone more smooth

granite pebbles more marble

and what can politics tell me

of the soft landscape

of the body or the hard wiring

of sex or what can landscape

David Jaffin, Dream Flow

Shearsman, 2006, Paperback, 312pp, 8.5"x5.5", £10 / $17

ISBN-10: 1-905700-14-8; ISBN-13: 978-1-905700-14-1

Reviewed by Melissa Flores-Bórquez

------------------------------------

This book contains 459 short poems, all written in three or four syllable lines, cutting words across the line-break. Since Jaffin's 2000 "comeback" volume, The Telling of Time. Poems 1989-1997, there has been a more than yearly output of large books like this one, containing poems in this form. This is the first poem of Dream Flow:

Charles

it's that

held-in

density

color

ing out

As a spi

der's web

intensely

aware.

color

ing out

Apparently these poems represent a year's output (2005) which suggests many days where several were written, or perhaps long intense runs, cutting, writing. The sheer number may come from an urgency, or else an automatic impulse which was felt to resist editing down, so that a year's span could stand. This is the third poem:

In coming

Where

the line be

gan he

became only

there as

moving sha

dows direct

ionless

ly timed to

an unknown

cause perpet

uating a rhy

thm which

wasn't his

continu

ally in co

ming.

Many of these poems are didactic and it turns out that Jaffin, American born, is a pastor in the Lutheran (Evangelical) church in Germany who also publishes collections of sermons.

No big theme

s

left as a

child's eye

s bigger

than his

gassed ball

oon could

hold the van

ity of man'

s self-be

lief heaven

ly loosed.

Pompous

is when

those cush

ions are sea

ted higher

than your

own indul

ging self.

Tsunami

There'

s a voice at

the bottom of

the sea Darker

even than me

mory can re

cord Hidden

from the depth

s of its own

despondent

longings Un

til split o-

pen the midst

of those tropi

cal winds Cry

ing out for the

blood of all

those vanquish

ing victims.

Jessica Smith, Organic Furniture Cellar

by Michael Peverett

There's reviews I've found more difficult than this one – in fact, they're all difficult – but I don't recall ever starting to write a review so many times. Because Organic Furniture Cellar is a book that can lead you off in a lot of directions beyond textuality.

But I've decided that I'm not going to write about how I bought it, though I think that the way that poets like Jessica Smith and Anne Boyer have taken up Etsy ateliers – Etsy is a sort of handicraft version of eBay – is fascinating, and surely one of the more unanticipated impacts of the Internet on poetry. I'm not going to write about the continuity between OFC and Smith's other handicraft works (Sommarhuset is an object-poem consisting of sand, dried bilberries, and stolen items), nor about the persistent blurring of public and private art that runs through her work; I'm not going to write about the alarming openness of her LookTouchBlog or the recently published Discourse Networks; I'm not going to write about modern self-publishing, though OFC is a formidable argument for it, nor about the many talking-points in Smith's introductory poetic ("The Plasticity of Poetry"), nor about the uproar over Ron Silliman's enthusiasm, nor about that range-finding shell from Joyelle McSweeney. Most reluctantly of all, I'm going to junk my effusions about where the book was put together (the High Coast area of Ångermanland), and I'm not even giving way to botanical meditation about Smith's "tryckara flora / pressed flowers" (Did she really find Melampyrum nemorosum that far north?). But I would invite you to print out the full-colour version of this poem, because it works much better than the monochrome one in OFC.

Organic Furniture Cellar is subtitled Works on Paper 2002 – 2004. Jessica Smith uses the whole of the paper, and the quotations here are frankly adapted to make them easier for me to quote. (For example, I can't replicate the half-line drops that she often uses to make a top-down left-to-right reading impossible.)

And can we do better than start at the beginning, with the top part of "Passage"?

red mtn.

still hums with irreconcilable distance

74 distances hum like traffic

400

during the day and like crickets at night 14 15

picking white flowers

distances are magnetized, they

push us away, they

615 us

repel 101 that click click of watches

sunny and

rainy kisses, 108 degrees in the shade

raspberry fingers

durcchscheinende road-cut

sunsets

trans lucidity

dandelions' of memory the

first

dead white everything

In these poems Smith is riding an unstable equilibrium between something that can be more or less read (though not necessarily top-down, left-to-right), and something that is looked at in the more apparently simultaneous way that we receive a visual; something we can then examine, but our examination doesn't have a particular start or finish to it.

It's the difficult cusp. (By contrast, a poem such as Herbert's "Easter Wings" is fairly stably in the reading zone despite its obvious visual aspect; a poem like Peter Finch's "Instantaneous Magnetism", where the word magnetism appears about thirty times in a column down the middle of the page, is fairly stably in the visual zone, though you might read the odd word while you're looking it over.)

To keep us – at least for a while – where she wants us, Smith has a problem of balance. "Passage" is an example of where she gets it about right, and here's the top part of "90" where I think she gets it wrong:

7 hours

a winter drive

blue sky tangled white feathers

shedding that

tpke winter phase

24

hawks mass

Sometimes readers are their own worst enemies. We really want something interesting to happen, but if we start off (as we rather tend to) at the top-left corner and immediately see what the poem seems to be about, then hey, we stick with that, no further questions. And since winter drives are, to our lazy minds, pretty familiar fare, the page just dies on us.

I'm not saying this to nitpick, but because one of the ways to appreciate what's happening here is to see how new kinds of problem loom into view.

"Shanghai" is a stunning layout, two dragons that are shimmering, broken reflections on the water. In order to make it work, Smith has muted the verbal excitement severely: there's almost nothing in the words themselves but functional description (pink paper lanterns, deep green summer leaves). And it does work, once you experience the horizontal lines of letters as ripples, but clearly such a form is vulnerable to unsympathetic reading: if you don't want to involve yourself in the layout, then it's easy to complain that this is just travel-diary exoticism. Here it's the layout alone that stops this being merely an account of a memory and instead kicks off what Smith elsewhere calls "an exploration of memory... an entire mnemo-topological system".

There's an analogous problem in the time-dimension. The exploration needs to go to work on the memory-forming process and Smith understandably uses her own memories. Memories themselves are keyed to – though not of course unmodifed from – what she really thought or felt at the time. And this means no dressing up.

Think of a poem like Wordsworth's Prelude that is built around memories already formed. We are satisfied that it's based on real experiences but in fact we are allowed very limited access to them because the text has completely absorbed the memories and their origins into the composed discourse of the poet; as here, of the philosophical walks with Beaupuy during the "Residence in France":

And sometimes –

When to a convent in a meadow green,

By a brook-side, we came, a roofless pile,

And not by reverential touch of Time

Dismantled, but by violence abrupt –

In spite of those heart-bracing colloquies,

In spite of real fervour, and of that

Less genuine and wrought up within myself –

I could not but bewail a wrong so harsh,

And for the Matin-bell to sound no more

Grieved, and the twilight taper, and the cross

High on the topmost pinnacle, a sign

(How welcome to the weary traveller's eyes!)

Of hospitality and peaceful rest.

How far we are from a direct transcription of the thoughts and experiences of the nineteen-year-old William (a fairly rough diamond, it would seem) can be gauged from the biographers' profound uncertainty and wide latitude for speculation about this part of his life. This isn't a narrative about the growth of a poet's mind in a psychological sense – though it's almost impossible for us to avoid that anachronism, so much has our concept of personal identity changed – it's a narrative about the development of his opinions.

The technical problem in OFC is that the rawness of those first thoughts is to be represented, and rawness is perilous: "your hand squeezes mine", "your rosy cheeks, salt-stained", "quiet Swedish ögruppen" (groups of islands), "crossing streets with tree names", "deep blue flatness", "the roar of the sea", "languages and places switching places"... It would be unreasonable to object to the private thoughts considered merely as thoughts – would yours read any better? – but we're so habituated to picking out this kind of phrase as a damning sign of insufficiently-realized poetry that, seeing these words in a poem, a knee-jerk condemnation is hard to suppress. Yet Smith needs the raw thoughts as material to explore memory-formation.

So it creates, once again, a delicate issue of balance. "Common Blues", "January", "February", "Delaware Park", "Brookwood Forest" are poems that I never begin to read in the way Smith wants: I'm too distracted by the uncomfortable presence of naïve expression. But I admit it was no accident I picked on Wordsworth; at some level I thought of Hazlitt:".. the unaccountable mixture of seeming simplicity and real abstruseness in the Lyrical Ballads. Fools have laughed at, wise men scarcely understand them."

And because of other poems here I do have an idea of what the ones I don't begin to read might be supposed to do. Here's the top-most and bottom-most parts of "first leaves":

a

d s

red

w c i

fire explosion

k

tt l

d

yellow burnt

e bursts of

***

orange

little specks of brown

a

smell of wet leaves

like bananas ll

trees like fireworks brown

eaves some trees turn utterly yellow

more quickly than others

(I've missed out the middle third, approximately, of the poem.) To call this only a poem about autumn leaves misses the dynamism of the arrangement. As the eye moves from top to bottom of the page, it passes through several gradations. Topologically, we're passing from tree-tops to the ground. We're also moving outwards, from the first thing you see (hence the title), the focussed dramatic flare of red in the crown that makes you think: Oh, right, the leaves are changing colour, to a transformed perception of the whole scene; for example, to noticing the leaves under your feet, the smell of wet leaves. But there's a chronological motion as well as a topological one: from looking ahead (on the lookout) then to inspection and consideration (looking down). The "mnemo-topology" mimics the movement of leaf-fall; for the mind is seasonally-suggestible and makes the rhythms of seasons. You could also recognize in the gradation of the poem a movement from October to November. And like the leaves themselves the mind finally dries out, retaining nothing in words but the flat, analytical, noteworthy observation that "some trees turn utterly yellow more quickly than others". Thus reason hopes to prolong the brief flush of apprehension!

Probably the most impressive extended stretch in the book is the poems grouped as Exile. A poem like "first leaves" works with the simplest of apprehensions and in natural forms and rhythms, but Exile is concerned with negotiating a complex built environment, the city of Berlin, and with structures inherited from a built monolith in our culture, Joyce's Ulysses (the city wanderings are of course à propos): the poems become grid-like and criss-crossed, except – naturally – in the trapped domesticity of Calypso and the sentimental eroticism of Nausikaa. Lestrygonians fragments a cynical conversation about the Berlin Wall and the Gaza Strip; Cyclops settles into the numbed "myopia / my opiate" of train travel.

"Hör du ente klocka?" (Don't you hear the clock?) says one of the fragments in Archipelago, the last part of OFC, which idyllically tries to stop the clock in the High Coast, where the land is still rising nearly a centimeter a year, and former bays like Ulvön are cut off from the sea. (It's a shame that the Swedish glossary, promised in the introduction, is nowhere to be seen.) The urgency of memory, as a means of clock-stopping, is figured in the inconsequentially beautiful map-poems, and sends sad tremors through the final poem, "After The Hours / Riddarfjärden". Wherever Smith gets to from here, it can't be back.

runs again

and remember

street lights this life runs out

night

m stops running you see

you point

finally

even in alleyways thoughts command

when remember this

e

Jessica Smith's Organic Furniture Cellar: Works on Paper 2002 – 2004 is published by Outside Voices, 2006. Non-US readers can order it at SPD.

from 'Dogtown'

Carol Watts

[Click on poems to view full size. If you have problems viewing the enlarged images, they can be viewed on this alternative page.]

Ken Edwards, eight + six

-----------------------------------------

Reviewed by James Wilkes

-----------------------------------------

"Bring back the persons!" Ken Edwards ups and says in the book's first poem, "they are bipolar and splendid". They are voices off (Thomas Wyatt, Caspar Brötzmann, Lyn Hejinian) or characters (Zeno, "a dickhead in a BMW", a tortoise) who surface and sink in a phenomenology, a stream of experience.

The health of a stream can be indicated by large numbers of caddis fly larvae, aquatic creatures building cases for the self from local materials: shells, reeds, sand.

A sonnet by Ken Edwards?

These poems build their cases from the voices of internet and business, pub chatter and jazz history, information exchange and the jostling of thoughts very interested in art & the world:

When Jimmy Cobb hit that high cymbal / when the metal went liquid & blue / all the cats in the farmyard woke from golden slumbers / in the twilight of money(from 'American Music' / 'Smithereens' / 'Speaks Into Mobile' / 'Click On This' / 'Windows for Dogs', respectively.)

tell him I'm tied up Mandy I am / shirted and cufflinked up don't get all previous / with me!

Striped of shirt and lambent of tie speaks / into a mobile a pipette of value wants to / plug a surf belladonna

and fractured management / corporate policies. I have read & understood / and agree to the terms & conditions

and send graphics, text files & other / information to John. Fibrillating and seriously flaky.

Like Ted Berrigan before him, Edwards has written sonnets that actualise the blur between reading, remembering, perceiving and thinking, by collage (or perhaps I should say by assemblage – you can glue in lines from a Wyatt poem, or from a lecture by Hejinian, but can't you glue in a conversation or how you observed a man "up to his wrists in engine" – you have to stand these next to the others.) At its loosest the sonnet form is simply a receptacle:

Bebop Buddleia backup crashing why(the first two verses from 'Among the Lime Kilns and Dilapidated Pleasure Gardens of Lambeth')

Bring brouhaha haha to the dark a

Burning technically like a time the lights

Don’t sleep sense shapesh fish’n

Sense sensing lull to strengths precise

Bi biped peddle in the gel if to

You You don’t And she I write unless

Always crashing matter casts undo

Here the form is like a glass jar filled with lines of different coloured sand – or maybe not, if "nothing is like anything else", a line Edwards borrows from Eric Mottram.

There's a sensitivity to the way words can spark words, as in 'The Deep Ecology of Special FX' which cuts a caper round an unspoken name, the shape in silhouette of a butterfly:

In the dead weatherFragments from earlier poems return and evoke their other contexts, the patterning of a fugue. In the second section of the book, the urbane and quizzical cases of the self move closer to becoming little songs (sonnetti) – and some proceed in series. Here is the first in the series called 'Perturbations':

before the storm

in fields where copper

flows like butter

as though a small winged

insect were in there

wanting egress

your chest flutters.

In dead television time

a ghost highway links

somewhere to nowhere.

You don't want to be there

but it isn't there – it's here

and there's no place else to go.

You (a person)The book is prefaced by a snippet from Merleau-Ponty, which concludes, "the ultimate court of appeal in our knowledge of these things [life, perception, mind], our experience of them". A judicial analogy, but here it is case opened, not case closed.

at the keyboard (or away

from it). As if poised for flight

to lee of, great hush.

The wood in that floor

with a solid sheen to it

your feet, pointed

inward

Circumambient

sour

green cymbals are stroked

with great, great gentleness (ppp)

to produce longing (keening).

This ruins my eyes.

Francis Petrarch, My Secret Book

--------------------------

ISBN: 1843910268 / November 2002 / Pages: 112 / £6.99 / Hesperus Press

Reviewed by Edmund Hardy

--------------------------

The poet, despairing of his own mortality, is suddenly visited by a splendid woman:

After she had spoken I was still afraid; but I did manage to stammer out those few words of Virgil: 'How must I address you, maiden? Yours is no mortal face, your voice no mortal voice.'Her name is Truth, and there is another by her side.

I had no need to ask his name: his priestly manner, his modest countenance, his serious gaze, his sober step, the combination of his African clothing and (once he began to speak) his Roman eloquence – all made it clear that this was the glorious St Augustine.The poet's torpor, his "acedia" (a humanist version of "accidie", the sin of sloth, related here to the Ciceronian "aegritude"), has now brought the greatest doctor from his eternal meditations, and the resulting dialogue – with Truth silently in attendance, her face lighting the alternating lines of thought in this exemplary doubling – will cure the poet, answer his cries with reason; and the cure will be our cure too.

Secretum (My Secret Book) is part of Petrarca's large body of work in Latin, which also includes various letters and treatises on subjects such as the solitary life and religious virtue, moral biographies, a popular work of self-help, De Remediis Utriusque Fortunae, as well as a guidebook to the Holy Land, Itinerarium. He worked continually, and famously, on Africa, his unfinished epic poem of Rome and Carthage, perhaps his best known Latin manuscript. Secretum is a revival of the classical method of arguing in utramque partem1, and the form would go on to flourish2. For the Renaissance dialogue tradition partly inaugurated by Secretum the classical culmination of the form was to be found in the works of Lucian and Cicero, particularly, for Petrarca, in the latter's Tusculanae Quaestiones (Tusculan Disputations). Secretum contains all sorts of contradictions(Cicero revered, but also the chosen interlocutor St. Augustine), though there is movement forward to no sweet concord.

Was it truly a secret? There was no copy of Secretum made in Petrarca's lifetime, so the work was certainly private; after his death, Tedaldo della Casa, a Franciscan friar from Florence made the first copy from Petrarca's autograph. If the book is a personal confession, spurred by guilt over earthly passions and that one consuming love for Laura, then it is an oblique one, spoken through a mask, and it is shadowed constantly by an apology. Augustine and Francesco have equal space to make their arguments, Augustine admonishing the poet for his torpor and distraction, Francesco stating the opposite, arguing – in the third dialogue out of three – that his love for Laura is love for a noble soul. In setting out, plainly, the argument against his own indulgences, in the printed speech of a great exemplar, a Christian argument of reason before imminent death, and then setting that argument to attack a presentation of the poet's own justifications, the Secretum would be a constant companion to incite up-building.

Schlegel's idea of the "wisdom of life" (Philosophie des Lebens) which escapes from school and into the novel would be on Francesco's side, arguing for passion; Schlegel cites Sperone Speroni's theory of dialogue as set out in Apologia dei dialogi (1574) where a conversation is figured as a pleasurable labyrinth ("piacevole labirinto") in which we may linger, or a garden full of many fruits, an image we may readily find in Castiglione but only passingly in Secretum, where Augustine claims that a variety of plants in a small space shade each other out: you should be fixed on thoughts of death, never allowing death to be a thought in the distance. Any attempts at conversational digression or storytelling are cut short, attempts perhaps to "go outside" ("Noli foras ire, in te redi; in interiore homine habitat veritas"3 – De Vera Religione, XXXIX, 72) instead of turning inwards into your own dividing.

In the first dialogue of Secretum, Augustine admits, "I did not change myself until deep meditation had brought all my unhappiness before me". For Francesco, in his despair, the "worst thing of all" is "Everything I see around me, everything I hear, and everything I touch." You will your own unhappiness, argues Augustine, contrary to Francesco's bemoaning of Fortune's portion. It is a Christianized revival of Epicurus' just and enlightened rationality which can examine motives and causes in pursuit of happiness and peace of mind. Petrarca makes Augustine particularly bracing when he dismisses justifications for the love of Laura, and hence all those famous sonnets:

As for saying that she drew you apart from the common herd and taught you to aspire to higher things, what does that mean but that she made you so devoted to her alone and so taken with one person's beauty that you found everything else despicable? You know that nothing in human society is more annoying than that.If you want the rest of the world to be more conducive in pleasing you, then, says Augustine, you are as arrogant as Julius Caesar when he said, "the human race exists for the sake of the few".

The public can lend glory in their praise (of literary work) and they can destroy the good with false opinion and coarse talk: leave the city, says Augustine, "In the long term it would also be helpful if you could accustom yourself to listening to the din of human beings with some pleasure, as though it were the sound of falling water." This is the civic fountain which is also the potential spray and source of parity, that same realisation which came to Propertius,

Cui fuit indocti fugienda et semita uulgi,J. G. Nichols more usually translates from the Italian, work which includes the Canzoniere (Carcanet, 2000), an edition with peerless notes; here his translation from the Latin is concise, often bringing the varying lengths of different clauses into English, an effect which sets this apart from Carol E. Quillen's translation (The Secret, Bedford Books, 2003). It is a pity that the Hesperus Press format does not allow for even brief footnotes which would open out the text a little more, though perhaps the constant quotations and references do send one back to Horace, Cicero, Virgil and Augustine's own works (which are often paraphrased here) to follow up links more fully than if handy footnotes were always providing a contextual digest.

ipsa petita lacu nunc mihi dlcis aqua est. (II.xxiii)4

This edition also contains two bonus tracts. 'A Draft of a Letter to Posterity' is a jumble of places and patrons, amplifying the argument on fame and the poet's desire for glory in Secretum. 'The Allegorical Ascent of Mount Ventoux' describes the pain of going astray from the right path, choosing the easier path which goes back down into the valleys, this an expansion on the idea in Secretum of choosing the wrong path at a fork, "You should in fact avoid those tracks which are trodden by the many and, striving for higher things, take that way which has fewer footprints on it" as Augustine says, suggesting that the choice will make all the difference. In this secret book, your moral unhappiness can be laid out before you as a field of agony even as a path of dialogue (il sentiero dei dialogi) winds through to further disparate horizons.

Footnotes

1 Arguing contrary positions.

2 I recently also wrote a review of a contemporary conversation novel, Gabriel Josipovici's Now.

3 "Don't attempt to go out; come back into yourself; within the human being is where truth lives." (My translation.)

4. "I, who once shunned even the street the crude mass takes

now find water drawn at the public cistern sweet."

(Translation by Vincent Katz.)

Two Poems by Joshua Stanley

Two Poems by Joshua Stanley

It is a persistent floatation on the glass, the conflict there

between passengers & the forecast latest.

It is a speech up, & a separation of

concept there, there out on the pane, the final season

& the door is closed. We had never

opened it & looking through the grass

stains on shoes are noticable & even casual.

Though that is not the cause, the crowding is

& I about discovery can look

through the screen & at the sight with

rest. That is music, the height of it

's coming together, the chance to turn it

around. There are the best laid plans

if we can search out the morale off of

& deep the beaten ship all out & in the open

before the cataclysm comes in the wash.

They cleaned the screen, before, & they

will do it again. Marigolds would be on the path.

It is a pasting spread, the light, it never

ends from the bulb & the primary consult.

I will wait. & I can

watch the handle if you want.

Only if you want. Do.

The exchange of temperature unfelt bent blades of grass

is essence tension to a shift in space,

out of Roland's curvaceous horns fugue

it arrives to the day in completion, black vs yellow.

Winds roar while the meniscus surface of

the rain gage itself can do "so" to the glance

bare as it is the effort, out of permanence,

as out of the starlit stammered, known &

familiar. More than that, a veritable imprint is

like the sound, it is a damage to roll over.

The neck is swan-like & the raspberry canes

dead. This year's lacking drought. Are wasps though.

Two is a gallery of many layers for this weather,

gladness that no shells were brought back

here & the decorative spills over

by the tunics set up as guards to the crows

when absence is avoiding you.

Leave the backdoor unlocked.

(The occasional mower's hum.)

An interview with Frances Presley

Frances Presley was born in Chesterfield in 1952. She says, "My defining moment in poetry came in 1969 when I first read Ezra Pound's 'Lustra'." Her first collection of poems and prose was The Sex of Art (North and South, 1988), followed by Hula Hoop in 1993, and Linocut (Oasis Books, 1997). In 2004 Salt published Paravane, a selected poems 1996–2003.

Earlier this year, in April, Shearsman published Myne, a companion survey to Paravane, with two new works, 'Stone Settings' which puzzles over the neolithic stones of Exmoor, and 'Myne', inspired by the Somerset landscape.

Frances Presley in conversation with Edmund Hardy:

EH: I'd like to ask you about puzzlement. 'Stone Settings', a new sequence published in Myne, begins with a note quoting Hazel Eardley-Wilmot's Ancient Exmoor – the stone monuments as "Exmoor's special puzzle". The title poem begins "per pl ex // moor". Through the sequence, it seems that you are not trying to solve this puzzle, by archaeological or occult speculation, but you are trying to see it from different perspectives – from the air, from other texts, from the mapped ground. What led you to think and write or trace out the stones?

FP: The 'stone settings' project came about for various reasons, such as my life on Exmoor and the desire to find a new aspect of it; as well as new ways of treating the visual layout of the page and its relationship to forms in nature and human invention. When I came across the existence of stone settings I was delighted: they were something extraordinary and unique and also rather comical. For those who don't know, what is unique about the stone settings is that they are not the familiar stone circles, longstones or stone rows, but they are a variety of roughly geometric shapes, and sometimes even apparently random. These characteristics make them particularly appealing to a contemporary poet and the curiosity of these strange configurations is part of the pleasure of being puzzled. The puzzle of the Neolithic stone settings is only one of the puzzles which I explore in the sequence, and it is the framework which opens out a whole series of associated concerns, which form the layers of debris and complication, both on site and in the archaeological texts. Although I came to know quite a lot about the archaeology of the stone monuments, and the work of estimable female archaeologists such as Hazel Eardley-Wilmot, it was not my intention to behave like an archaeologist. I was as interested in what we failed to find, and the process of that failure, as I was in the actual finds.

'Stone settings' do approach this puzzle through a variety of different means, and although this is not attempt to 'solve' the puzzle, and certainly not from an archaeological or occult perspective, themes do emerge. I approached the puzzle by various methods. These included writing on site and allowing the site to 'dictate' the formation of the language, a deliberate permission of non-sense. Unfortunately due to bad weather and the remoteness of sites this proved a more difficult technique than expected! I began to reconstruct archaeological texts and extract their sub-texts. I returned to the discontinuous prose poem, used extensively in Somerset Letters, and which allowed me to write off site: it can also incorporate narratives of community and history.

EH: "Debris and complication" seems like a poetics! To some extent it seems that the space between the stones is what interested you, or it's this space which has also provided a new way of thinking about the page, "dictating" the formation. How would you describe the new ways of treating the visual layout in 'Stone settings', and the ways in which your thinking about page-space has changed, or changes with each new project?

FP: You're right to emphasise the visual significance of this project, and my interest in the visual layout of the page has been influenced by developments in contemporary poetry. 'Stone settings' is a collaboration with the poet Tilla Brading, whose interest in the visual possibilities of poetry was already well advanced, and involves the use of digital technology. I hope that some of her images will be on display when we read at 'Crossing the Line' in London in November.

I've written about landscape poetry and the space of the page for a forthcoming book on British ecology, edited by Richard Kerridge and Harriet Tarlo. My interest in the visual arts and poetry goes back to my studies in modernism and surrealism, as well as collaborations with artists such as Irma Irsara, but my experimentation with layout on the page was slower to develop. I'm especially indebted to Kathleen Fraser for drawing my attention to contemporary women poets and the visual arts in a post-Olsonian context. The cross-over between art and text is very marked today amongst experimental poets and artists; although poets sometimes resent the fact that their texts are considered of lesser value than those of artists, because there's no money in poetry!

'Stone settings' did seem to provide an ideal focus for developing this interest, as it provided an actual layout or the remains of one, which I could choose to follow or re-interpret. There is the sheer physical pleasure, or discomfort, of exploring the layout of the stones, not to mention the sheer frustration of not finding them! We had plans to undertake various exercises on site, and amongst other influences was that of the artist Richard Long's traces and arrangements. Although some of these were undertaken, conditions were rarely ideal and there were all kinds of unavoidable interferences with our expeditions, such as the weather and the inclusion of other people. This probably says something about the purity of the art which was our model, and although, in a sense, the outcome was failure, it was also a strength that we engaged with the impurity of being.

To draw a straight line on a map or on the ground is a highly artificial exercise. It can also be an extremely satisfying one and appeals to our desire for order. One of the themes which emerged, in a prose-poem like 'Brer', is the power of geometry as such, and the appeal it has to those who feel most comfortable with computational exercises. I wanted to understand that drive, while placing it alongside other events and interruptions. The most geometric page layouts are those which are text derived, such as 'Stone settings' and 'White ladder', and these express both perfection and an underlying irony about perfect form. We were, for example, wholly unable to find the double quartz stone row of 'White ladder', even with the help of the Exmoor archaeologist!

EH: The failure, as you put it, could then be the failure of a Romantic art where a people is missing. Long is sometimes accused of wilderness Romanticism. The impurity you mention as a strength, seems to be a way of writing a landscape poetry which is complicated by being peopled; the prose poems a different

way?

FP: Yes, that's right, and I think the emphasis here is on 'peopled': the multiplicity of voices that exist in any landscape, in any discourse, and our responsibility to listen to those voices, as well as the recognition of our own very limited line of sight. The contemporary prose poem can incorporate some of those voices while ensuring that there is no master narrative. To quote 'Brer': 'How can we follow these parallel lives?' I am much more concerned about parallel lives than about parallel lines. I also like what can be achieved by tight juxtaposition, or parataxis within the prose poem, and I think I also find it useful for oblique political analysis. Unexpected transitions can be more powerful, I think, because they are encapsulated within an apparently seamless style. They are small explosions on a calm surface, such as this one in 'Triscombe stone': 'She has been driven to many aboriginal sites. There is proof of global warming at last.'

It's also the case that this is a collaboration, and there was already a process of two voices engaged in a conversation, and the need to respect differing approaches and interests.

EH: The last poem in the sequence, 'Culbone (1 October 2005)', has a note mentioning Walter Wolfgang's ejection from the Labour party conference for saying the word "nonsense", and the word also appears in the poem. How did that event and the "one word" spoken strike you, as you wrote the poem the next day?

FP: This was an example of an external voice influencing my experience of a site. It's an example also of my concern with the present, and where I would diverge from archaeology, the main focus of which is a responsibility to the past. I was reading an account of the conference, and an interview with Walter Wolfgang, on my way to Porlock Weir. You can probably infer my feelings for the Blair Labour Party, from my use of 'New Labour' in the footnote, which you have slightly modified! I was working in community health when Alan Milburn took over, and the next two, very difficult years, were spent campaigning and lobbying parliament, trying to make our voices heard. There are references to this experience in the 'Paravane' sequence (published by Salt in 2004).

On the day in question I was hoping to reach Culbone stone row, but I was diverted by bad weather, and decided to take shelter and write in Culbone church. As is often the case when I'm alone at a site, I engage initially in techniques drawn from automatic writing, a controlled improvisation. I don't want to predetermine the outcome of the text, and I also want the site to influence the language that I use. However, another, local, voice had already entered into my mind while sheltering earlier at the Ship Inn at Porlock, the only visitor that morning: the woman serving me had begun to talk about her husband, who was in the army, 'on exercises'. From then on the political strand within the poem begins to establish itself. The 'point/ low' becomes primarily political rather than simply the turn of the season. Oppositional statements are voiced and revoiced in various ways. In the past, working in social welfare, I have been accused of being negative and even subversive, especially under the Thatcherite policy of slimming down organisations and stifling dissent. Within the text the negative moment is also defined by a paring down to a single word of protest – the only one that Wolfgang managed to utter before being bundled out. This process of reduction and attrition affects the language itself, and create examples of what some define as 'infraverbal minimalism' in which the words themselves are torn apart, such as 'commsate' or 'cr mmml'. In this poetics of 'nonsense' an oppositional energy is released. At the same time the focus of the poem shifts to a spiritual debate, imposed by the physical space of the church. It is, notably, a plainly furnished Protestant church, with an emphasis on 'white' space and transparency. The memorial inscription to 'Charlotte' in this poem can also evoke the spirit of Charlotte Bronte, the Protestant minister's daughter. I am amused by, and critical of this reformed religion, while retaining some allegiance to its bare philosophy. I leave almost the last word to Wolfgang, because I found his statement a powerful and moving testimony to the effect of words, of a word: the sense of nonsense. His phrase 'smooth words', applied to the rhetoric of New Labour, also has echoes for me of Edmund Burke on the ideal landscape (or discourse), as opposed to Mary Wollstonecraft's rougher response.

EH: I've been reading Burke's Letters on a Regicide Peace recently – it's like an epistolary map of a conservative century to come, adaptation as political power. The other new sequence here is 'Myne' – each poem located by month and place, "in and around Minehead". I was interested by the literal lines which appear. I read the first one as a writing hand slipping – but others seemed like tracings. How did these get into the poems? Also, did you really read Martin Eden on a knoll?

FP: The 'Myne' sequence was written almost entirely 'on site' with some later revision. For that reason I used the kind of improvisation methods that are present in the 'Culbone' text. That means that every gesture is significant, and I try to revise and censor as little as possible. The 'literal lines' as you call them could be, as in the case you refer to, a hand slipping, or even the obscuring of words by the elements. I think that in 'December in St Peter's' I was literally dripping rain water onto the page!

I also sometimes sketch as well as write, and I include that process (though not the drawings) in 'June on North Hill', which is subtitled 'blind drawing'. The artist's technique of 'blind drawing' is one where you draw without looking at the page in order not to distract the eye. It's a technique I sometimes use when I'm writing outside, and, rather as in drawing, it produces a very different quality. I did try to discover if there was an equivalent technique of 'blind writing', but all I could find on the internet were some business brainstorming methods!

The rising curved line which begins 'March on North Hill' is an approximation of Dunkery hill, the highest point on Exmoor, but obviously it isn't a sketch. I'm not sure if I should include sketches, and that also raises the issue of incorporating handwriting. I can think of instances where handwriting has been included, such as the cover Dell Olsen made for the collaboration I did with Elizabeth James (published by Form books), and that too adds another dimension.

As for versions of eden on a knoll above the sea… Some years ago I was studying Martin Eden for an American literature course, while organising summer school activities. I had some delightful students who were picking blackberries further down the hill, while I could get on with my reading. I have a fondness for Jack London's Martin Eden: his lightly fictionalised autobiography. I have no great affinity with his autodidact's fascination with the Ubermensch, but his depiction of the difficulties of the working class writer are memorably described: there's that scene where he turns an editor upside down to get the money out of his pockets. I suppose a later equivalent for women would be something like Tillie Olsen's Silences. Eden is particularly incensed at the treatment of his poet friend (based on Hart Crane?) who only gets recognition after his death. As I remember, at the end of the book, Eden himself commits suicide by jumping into the sea.

EH: Is the image of a work by Irma Irsara (for the cover of Myne) your choice? If so, what attracted you to this piece?

EH: Is the image of a work by Irma Irsara (for the cover of Myne) your choice? If so, what attracted you to this piece?FP: The cover image 'Una Finestra per un licheno' ('A window through a lichen'), by Irma Irsara, was chosen collaboratively. We have worked together for over ten years now, and we also live quite close together in Islington. Our main collaboration, 'automatic cross stitch', was a study of the fashion industry in north Islington. Irma originally comes from a mountain farm in north Italy, so we share a passion for landscape. Before I knew her, and not long after she came to England, she did a nature conservation course in Somerset, with the idea of becoming a forester, and she's quite an expert on lichen. This image is fairly typical of her work. It is abstract, multi-layered, and with an intense use of colour: a recent exhibition was called 'La Favella di Colore, and the old Italian word 'favella' suggests a more lyrical kind of speech. She uses a hand-made paper technique to literally build up the image, layer by layer, and will often incorporate other materials: this one has wool in it, and we picked up that grey-white colour for the background. Since Myne covers such a broad range of my work and life, I did not want an image which would reflect one particular sequence too closely, while retaining an association with the emphasis on landscape. Collaboration continues to play an important part in my life, and I wanted to thank you for the opportunity to have this conversation.

EH: Thank you, Frances.

Conversation by email, September and into October 2006.

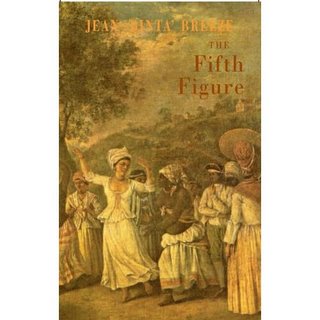

Jean 'Binta' Breeze, The Fifth Figure

Reviewed by Abena Sutherland

Five women speak, five generations of one family living in rural Jamaica, peasant farmers. Each woman is given a chapter before we move on to the next figure, the next voice. This is – in part – a family memoir, beginning in the late nineteenth century. The five figures are also the figures of the quadrille, a dance which plays a pivotal role in each life – later, the mento band followed by a walk home through the bush amid the wild tumeric – the first, second, third, each woman learning the next figure of the dance.

The great-great-grandmother's narration begins in a broken poetry which rolls along in short lines –

All the way across the island– until violence breaks the voice into a breathless prose, at first with constant gaps – stutters, a voice speaking at the limit while being pulled back – and then into long paragraphs, a plain narrative prose. The following three women all narrate in this prose style, rising to pitches of description, but not singing the short lines. The lives are hinged on childbirth, first the wakening of desire, then its aftermath. Each chapter can provide sudden reflections back, as, for example, the young narrator's perception of her crippled father – who we know continually drank rum and beat his wife – is not of a violent man but a lonely man who likes her company and the telling of old tales. What knowledge should be passed down from mother to daughter? It is as if the tales and scenes accumulate, down to the fifth figure: Sarah, who is able, at last, to speak her monologue in lines of poetry again, and we read her as Jean 'Binta' Breeze's double, learning songs, patois, narrative pieces, and taking them – in patchwork – to an international audience, yet with her life and art routed back through Jamaica, a home on that hill side.

I was eaten up by green.

Lush green like it was burning

where it flowered into red

and the shocking nature of the scenery

left me feeling quite numb.

I, so overwhelmed by colour,

felt completely naked in the sun.

The beautifully designed cover uses a detail from an oil painting by Agostino Brunias, 'Villagers Merrymaking in the Island of St Vincent' (below).

Brunias was a painter born in Italy in 1730 who studied in Rome then worked for the Scottish architect Robert Adam, moving to England from where he travelled to the Caribbean in 1765 as personal artist to an English government official, William Young. With a break in the middle for a return to England, Brunias spent over two decades in the West Indies, living on Dominica but visiting the other islands. His paintings of West Indian slave life are idylls, this picture of merrymaking and dance is saturated with a brown tint, different shades blurring and brushed over by wider swirling patterns. The dominant figure is the lighter skinned woman, a movement in the frame from darker to lighter noticeable in other Brunias paintings, reflecting the mixture of white and black ancestry right from the start of The Fifth Figure. Derek Walcott could have been talking about this painting when he wrote, "Deprivation is made lyrical and twilight, with the patience of alchemy, almost transmutes despair into virtue. In the tropics, nothing is lovelier than the allotments of the poor, no theatre as vivid, voluble, and cheap." (What the Twilight Says: Essays) This lyricism is emptied out in the prose accounts of The Fifth Figure - the dancers reveal their own steps, the traps and escapes of their lives:

I learnt how to pick mangoes with Nana, how to aim and throw straight, at the stem, not the fruit, so they wouldn't suffer a bruising, and now I know if the children come back, I shall stone them down like ripe mangoes.Each section reads like a family testament. The speed of 80 pages to contain five generations leaves the impression of an album, turned through. Here great-granddaughter Sarah echoes Susu above:

I walk home quick

As soon as the school bell ring

But a group of boys from the common

Now following me all the way

They shout at me

They pull my hair

They throw my books in the bush

One day as I reach the gate

I pick up a stone and fling

Just like I use to fling in Hillside

Fling pon the mango tree

Tom Lowenstein

At Uqpik's Cabin

Capping the ruins and scattered through the village stood the 19th century traders' cabins: tightly constructed clapboard houses with thick tar-paper insulation. Five of these houses, dragged back from Jabbertown1 along the south beach in native skin boats, survived in the village.

Uqpik's stood near the western end of the peninsula. It had been Max Lieb's cabin, bartered by his family when Lieb froze to death in 1902 on foot to the village from Cape Thompson2 where he had been starving.

Lieb's house stood alone on flat ground near a grassy beach ridge, set round with iglu pits and their ruined whale bone tunnels. ------ Still more remote, and infested with families of wild, nesting huskies, stood Asatchaq's cabin. Sixty years back, his father Kiligvak, 'the mastodon', had built it with lumber he bought from a Jabbertown trader - the first native frame-house in the village.

Perched near the south-west tip of the point, as though set to spring for the sea ice or the open water, the house, with its desolate window and broken chimney, was the furthest northwest building on the continent. Uqpik was its closest neighbour.

I'd stopped here, though the backpack nagged my shoulder,

and watched a flight of longspurs feeding.

It was midday, and a hard wind rushed across the tundra.

I was sweating and cold; my feet were swollen.

Still the outdoors held me.

To enter this soon, was too soon, so it told me.

The south wind grew violent.

It tore at the insulation on the corners which had broken

from their seams of deep, flat 19th century nail heads,

buckling the east side where the dogs lay tethered.

I clambered up the northwest corner.

Ox-eyed daisies, hinged to broken turfs around the house base,

rapped my ankles. Camomile tapped, as though knocking to enter,

the edges of my boot soles.

Qanitchaq! Qanitchaq!3

As if no feet had ever broken through

the stepped frets of the labyrinth!

I glanced along the shed roof. There were caribou blankets

pocked with thick eyes gnawed by warble-fly larvae;

some gulls, half rotted, plumage withered,

beaks and claws in pieces, lay sprawled in a bundle.

Other remainders of game, traps, hunting tackle lodged here,

anchored with long curving whale jaws,

and runners, like horns, of snow-mobiles, exanimate,

stuck through some chassis that was rusting among discs and vertebrae.

A soul scuttled through the frieze of apparatus and detritus stored here.

Torsos clamoured from the scaffold to retrace their bearings.

Midday winked. The fable mended. Red-fox-and-snowy-owl.

They'd been just on the trail through their sublunary offices,

When the hunter - with an invitation for exchange and sociality - had detained them.

The fox squeezed out of his shriveled costume.

He'd dressed in it only once too often.

Earth had grown skinny.

No more fox tracks, no more ruckus.

Day ticked forward. Sun and wind rotation.

The high disc shone through coat and muscle.

She'd been trapped in her nod, in her snow and soot plumage,4

Eyes shrouded on his vertebrae,

His tooth on her shoulder, her beak on his sternum,

Abrasively kissing, dialectically embracing,

Cross-hatched with each other,

When death entertained and finally engaged them.

I tripped the latch, my thumb sliding on the runnels

where eighty-five years of seal-oiled fingers

- hunters, Yankee-German traders, native wives and their 'half-breed' children - had polished and unfixed the catchment.

It was twilight in the passage: the floor, defrosted tundra,

caving beneath plywood panels that squelched in the mash

and rocked from the centre as the inner door I sought emerged from the dullness.

The horns of my backpack scraped a high shelf where I faltered,

wrenching the left shoulder, scapula extrapolated from its matrix

(on a photo-plate I felt it, geometrically projected) on the screen of entry

where I staggered to control the threshold.

Inside the room was black

as the tarp5 I heard flopping and had seen it wagging from the east side

where the dogs slept flat-out in the grass, forget-me-nots and daisies.

The dazzle of that blazed outward to the window,

the scarred glaze of which gave back to the grass

and heaped lost rusting ironware: cans and barrels,

1950s pots and skillets, a discordant, dislocated aluminium kettle,

all the old American etceteras, accessories, disjected recent membra

scattered, half-sunk, stuck together -

itkaq was a verb I later gathered:

'to throw out, or abandon on the midden'.

Pah! I'm gonna itkaq this junk finally, I heard Suuyuk next year -

the dazzle of it rang, like brass splayed clean to brazen needles,

a clash, screwed-up, blazing musically

from the corners of the eyes which had dried in the wind-blast

and now tried adjusting to the darkness and its complex odour:

seal-oil, fuel, excrement and urine half-masked in a whiff of disinfectant.

There was a table where a pot of peanut butter

stood with a buck-knife handle sticking out of it:

twisted antler of the type you get from pawn shops

down in Sioux Falls, Laramie, Billings Montana, and on Fairbanks

2nd Avenue: masculine equipment.

Deep in the jar, the blade was set in folds of peanut butter,

the shrouds clotted with lumps of smashed peanuts and jelly:

while gazing from seal oil - golden, viscous,

in an emptied can of Skipjack tuna - I caught my reflection:

dust-fur on the tin's edge, spiked as the wolf-ruff

of a parka hood, enveloping my hat and collar.

A sharp snore and the rattle of a sleeping-bag abraded my fixation.

The thrash of nylon from a recess screened with plywood burst forth,

and a young man in an insulated boiler suit, grease-stained, ripped and puffy

shambled from the bunk-space where he had been sleeping,

and with mouth half-open to receive his Winston,

eyes doubly sunk in epicanthine ruins

- as though some clan-fate in a Kuniyoshi theatre vision6 hatched his levee -

stood and watched me levering my pack down.

'You got everything?' the young man asked -

as if, in courtesy, receding from a space once his,

in forethought he liked me without bothering to plot the detail,

grasping that my presence, unexpected, was some commerce of his seniors -

and went back to sleep behind his partition.

'Okay,' I mumbled. I was irritated and embarrassed.

I wanted the whole cabin.

I settled my stuff and, disconcerted primly somewhat, looked round

at the textures of the house interior.

There was gravel on the floor and table; the insulation on the walls and ceiling,

webbed with soot from oil fumes, sagged dangerously inwards.

A near-century of grease from countless animals

hauled up and butchered in the family circle gleamed

from every surface. Surrounding the peanut butter jar, on oilskin

scarred by ice picks, knives and cigarette burns,

were sugar, sardines, tuna, jars of instant coffee,

Pream, teabags and used teaspoons,

cogs, brackets, bolts and wrenches, screwdrivers and brake-wire:

the truck of subsistence: abrupt indoor leavings

of out-of-doors business: meat, work and fuel of hunters and mechanics.

A men's house. Uqpik's wife had died five years back,

and I missed her for them.

Next I was drawn to a length of gingham in the north-east corner:

a rucked, shabbily suspended, hand stained curtain,

from which fumes of Lysol swayed through the twilight:

the communal sump of several days' evacuations.

Converging here, as anthropologists had warned me they might,

were all my prudery and learn'd aversions, masked previously

by bathroom culture, tiling, enamel and glazed sanitary polish.

One glimpse of the crusted bucket-handle, and the clusterings, blurred,

of excrements half-melted at the loose brim of that dark infusion,

and (impotent in toto, but to pitch in still quite anxious) I fled the house cringing.

Outside, the air was rough and simple.

I walked to the beach and gratefully relieved my lower person,

though the wind shook my equipment, and a flurry of snow

gusted down from the north which was paralysing to the sphincter.

*

A mist had come in and sunlight ran

in shafts and pieces through it.

Then rising on the Point ahead

was an arch of whale's jaw-bones,

two mandibles curving

against grey, half-hidden tundra.

The bones faced one another,

and their broad ellipse narrowed

at the high point without touching,

but stood open, enclosing in their tension

a long framed view,

through which, as I circled,

the village, sea and tundra,

were rotated: the tips of the uprights

vanishing in mist as though,

where it drifted in the sky between them,

the dead whale's vapour hung suspended:

breathed out to the faces of past hunters and women.

At the jaws' root in the long pale grasses

were three sets of tripods fixed waist-high:

whale ribs lashed in a ritual grouping,

where the skin-toss game

to celebrate successful whale hunts

was held in the spring time.

Then as I stood, I saw blow in

the flock of whimbrel.

There were eight, perhaps ten.

Streaked, mottled and lean-legged,

arched beaks drawing them

from somewhere they'd been feeding,

bills airily balanced

with the whale bone archways,

and cumbrously perched in calm

on their migration, they lifted and fell

slowly, in exchange of places

between jaws and tripods.

I counted again. There were eight birds -

nine, then twelve, now eleven -

enlarged and then shrouded

by fog in their plumage.

The wind dropped

and I heard them whistle,

gauntly piping, one to another,

a bleak call, but not scolding

as gulls and terns do, nor like

kittiwakes' incesssant weeping.

So they shuffled, fluttered,

appearing to flounder,

air to whale bone,

dropping

one, and then another,

shuttling their pattern,

and jumping across,

they wavered - idle slightly -

restless, in some exercise

of voyaging or ritual,

the purpose

of their long migration

and this point of repose here

inexplicit.

*

'I've broken my tooth' said Uqpik later that day

as we met in the morning at the Co-op checkout.

'Are you going outside to see a dentist?'

'No, I mean the polar bear.'

'On frozen meat? I didn't know you ate it quaq7.

'The bear. She broke it. Maybe Asatchaq heard me.

He was sitting on a pressure ridge, and he listened to that nanuq.

She was talking to herself because her tooth was busted.

Didn't you know I am a polar bear?'

'I didn't. And you're not a woman are you?'

'No. But I had one last week. It was my birthday.

Piece of ass from Silavik!'

The kinks snarled sharply and then came unknotted.

He emerged from the story.

Asatchaq's cassette, scrolled crisply in its spindle

froze and went silent.

'That uqaluktuaq8,' I started, 'of the hunter and the polar bear

with tooth-ache…' 'We don't listen much to those now,'

he reported, as if forwarding a message

from his middle generation who had known them from their elders,

then disburdened themselves from the stress of too much ownership.

'Let the old man tell you. I won't tell you.

By the way,' he continued, 'how many poems have you written?'

And then: 'Here's one of mine. It's for you and about you.'

Tom Lowenstein came to Point Hope.

He went down to the beach.

He looked up at the sky.

Sea gull shit in his eye.

No sooner had Uqpik tuned his lyric,

to thus garland the honky9

with ironic laurel,

than his rebus became public.

The bird shit in my eye

was on everybody's tongue,

and was shaking their tonsils:

the old folks most severely,

they were heaving,

and the smokers had the worst of it,

bent in the P.O or the Co-op

far as their arthritic joints would let them,

crippled to the thorax,

sputum erupting, desisting at last

with low weak tee hee-s

as Uqpik applied to his latest consumer.

Years later I saw the man's mercury still running

when for Piquk's dog-team,

on a nasty, darkening March afternoon,

they cut together snowblocks,

and piled them in a semi-circle for a windbreak:

and suddenly, the construction done,

he grabbed some antlers.

They were lying in the general clutter,

and he raised them to crown his hat and hood-ruff.

I was sorting ropes and harness

and glanced up through the snow drift

to see his hat and thick black glasses,

horns raised above them,

cheek-bones queerly twisted,

and under the antlers, the Inupiaq laughter.

Then he started to dance

among the dogs there -

dug now well into their cover -

hands cupped on ears,

antlers branching from the deer-skull,

the rack swaying vertically

as Uqpik slanted.

It was simply a gag and didn't go on.

He chucked off the horns

in a heap of rubbish.

Nor might I have noticed some other joker.

And yet here,

in allusion, his geste, a footnote merely,

was spirit life as sketched at Trois Freres or at Mas d'Azil10:

the strutting biform - mixtumque genus11 -

in joking shamanistic evocation,

casually abandoned for tea and seal meat

and something dry, in Piquk's cabin,

to de-mist his glasses with.

It was this Inupiaq, but perhaps not him only,

in the cycle of lives he picked up and discarded,

who slotted in and then disordered

the shifting selves of surface and sub-surface persons:

where otherwise the continuity?

It was atiq on atiq12

juggling of future and past portrait dance-masks,

cached into packs of infinitely branching series -

a deep, violently cold larder -

shells of their faces stacked together,

foreheads of life 'One' pleated in the next version's fissure:

weren't they brittle and transparent?

Or was this spirit-skin more pliant

down here that they nourished,

each face fitted into strictly knitted kinship links,

and not free to disaffiliate,

or drift to resorts of their own volition,

improvised bearings and upside-downness13?

'Can I borrow your cheeks?' Uqpik went off joking.

'Mine are frozen.'

Those were rigid constellations

And the spaces between were ordained, unmoving.

Come and go you did not.

There was time in it there, with its limits and anxieties:

The forebears at large within the system:

An anterior medium, collective nekuia,

Down where finite populations travelled:

Webbed strings lit, intermittent,

And where meat, work, games

And procreation drove originating passages.

Rebirth came. It was repeated.

The reprises were foreseen: enchanted advents

Taken care of by habituation. All were

Involved always, and the involution spiraled

In a circle of repeated faces, softly figured,

Coalescent one with another,

As though features - colluding

In the long exchange of plane and angle,

The measure of a jaw, the set of cheek-bones

Or the clear range of a forehead -

Might shift and return, transform at the touch

Of sudden but predictable extra-consanguinity,

Wither in old age, go out, and then return

As though previously uncompounded,

And new semblances wrest, recalling

Patterns long forgotten,

Yet recurrently familiar

As collaborative life forms:

Past and future compassed in the present,

Circling each generation.

'Those polar bears know me,' Uqpik went on, later.

I'm not afraid of them. But they all know me.

Once I went out with Agniin, my sister.

We were on the sea ice - straight out there,'

pointing to the north side, towards Cape Lisburne.

'Where's your rifle?' asked my sister.

'I don't need a rifle. Those polar bears know me.'

So we went out further. Came to an ice pile.

'There's a polar bear behind that ice,' I told her.

She believed me. She knew hunting.

Then I shouted to it. Called out loudly.

Polar bear was sleeping maybe.

Then we heard its feet on the snow. And grunting, breathing.'

'Come on,' said my sister. She wanted to go home now.

'It won't eat you. I'll tell it not to eat you.'

Then that nanuq came round. It was quite a big one.

Mean and skinny. Sick, I guess. Hungry.

It'd been in a fight. Got hurt by a walrus,

maybe in its belly. That's when I started.

'Don't eat her!' I shouted.

'Come and eat me!' 'Arii!' said my sister. She was scared by this time.

'When it's eaten me, it'll have you for its supper.'

She turned her back and started to walk home.

'All right,' I told the nanuq. It could understand my language.

'That's my sister. I will follow.

She doesn't like you. But I'll come back later.'

Damn' if that nanuq didn't walk back behind me.

I stopped a while and tried to help it.

'Go and get yourself some seal meat.

Then I'll come and find you.'

Footnotes

1 Late 19th century whaler-trader's settlement 5 miles from village

2 cliffs 35 miles south of village

3 iglu entrance tunnel; frame house storm shed; traditionally locus of visionary events.

4 Evokes fable in which snowy owl and peregrine get speckled feathers when raven throws lamp soot at them.

5 Tar paper insulation

6 19th century woodcut artist of theatre prints.

7 raw frozen

8 ancestor story

9 Black American term for white man used in the village.

10 Palaeolithic cave sites. The allusion, at Trois Freres, is to a horned male dancer, sometimes known as 'the sorcerer'.

11 Said of the minotaur's 'mixed species', Aeneid 6.25. I've kept the here non-grammatical suffix -que to keep the phrase intact.

12 Literally 'name', but here also 'namesake'. Atiq was a soul component which was reborn into a child of the same name.

13 Upside-downness was a symbol of primordial chaos.

Acknowledgement:

A version of At Uqpik's Cabin was published by Shearsman Books in the title sequence of Tom Lowenstein's Ancestors and Species: New & Selected Ethnographic Poetry (2006). Thanks to Shearsman for permission to republish.