Jean 'Binta' Breeze, The Fifth Figure

£7.95 / Paperback / ISBN 1 85224 732 0 / 80pp / 2006. Bloodaxe Books

Reviewed by Abena Sutherland

Five women speak, five generations of one family living in rural Jamaica, peasant farmers. Each woman is given a chapter before we move on to the next figure, the next voice. This is – in part – a family memoir, beginning in the late nineteenth century. The five figures are also the figures of the quadrille, a dance which plays a pivotal role in each life – later, the mento band followed by a walk home through the bush amid the wild tumeric – the first, second, third, each woman learning the next figure of the dance.

The great-great-grandmother's narration begins in a broken poetry which rolls along in short lines –

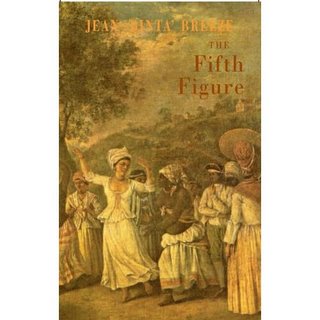

The beautifully designed cover uses a detail from an oil painting by Agostino Brunias, 'Villagers Merrymaking in the Island of St Vincent' (below).

Brunias was a painter born in Italy in 1730 who studied in Rome then worked for the Scottish architect Robert Adam, moving to England from where he travelled to the Caribbean in 1765 as personal artist to an English government official, William Young. With a break in the middle for a return to England, Brunias spent over two decades in the West Indies, living on Dominica but visiting the other islands. His paintings of West Indian slave life are idylls, this picture of merrymaking and dance is saturated with a brown tint, different shades blurring and brushed over by wider swirling patterns. The dominant figure is the lighter skinned woman, a movement in the frame from darker to lighter noticeable in other Brunias paintings, reflecting the mixture of white and black ancestry right from the start of The Fifth Figure. Derek Walcott could have been talking about this painting when he wrote, "Deprivation is made lyrical and twilight, with the patience of alchemy, almost transmutes despair into virtue. In the tropics, nothing is lovelier than the allotments of the poor, no theatre as vivid, voluble, and cheap." (What the Twilight Says: Essays) This lyricism is emptied out in the prose accounts of The Fifth Figure - the dancers reveal their own steps, the traps and escapes of their lives:

Reviewed by Abena Sutherland

Five women speak, five generations of one family living in rural Jamaica, peasant farmers. Each woman is given a chapter before we move on to the next figure, the next voice. This is – in part – a family memoir, beginning in the late nineteenth century. The five figures are also the figures of the quadrille, a dance which plays a pivotal role in each life – later, the mento band followed by a walk home through the bush amid the wild tumeric – the first, second, third, each woman learning the next figure of the dance.

The great-great-grandmother's narration begins in a broken poetry which rolls along in short lines –

All the way across the island– until violence breaks the voice into a breathless prose, at first with constant gaps – stutters, a voice speaking at the limit while being pulled back – and then into long paragraphs, a plain narrative prose. The following three women all narrate in this prose style, rising to pitches of description, but not singing the short lines. The lives are hinged on childbirth, first the wakening of desire, then its aftermath. Each chapter can provide sudden reflections back, as, for example, the young narrator's perception of her crippled father – who we know continually drank rum and beat his wife – is not of a violent man but a lonely man who likes her company and the telling of old tales. What knowledge should be passed down from mother to daughter? It is as if the tales and scenes accumulate, down to the fifth figure: Sarah, who is able, at last, to speak her monologue in lines of poetry again, and we read her as Jean 'Binta' Breeze's double, learning songs, patois, narrative pieces, and taking them – in patchwork – to an international audience, yet with her life and art routed back through Jamaica, a home on that hill side.

I was eaten up by green.

Lush green like it was burning

where it flowered into red

and the shocking nature of the scenery

left me feeling quite numb.

I, so overwhelmed by colour,

felt completely naked in the sun.

The beautifully designed cover uses a detail from an oil painting by Agostino Brunias, 'Villagers Merrymaking in the Island of St Vincent' (below).

Brunias was a painter born in Italy in 1730 who studied in Rome then worked for the Scottish architect Robert Adam, moving to England from where he travelled to the Caribbean in 1765 as personal artist to an English government official, William Young. With a break in the middle for a return to England, Brunias spent over two decades in the West Indies, living on Dominica but visiting the other islands. His paintings of West Indian slave life are idylls, this picture of merrymaking and dance is saturated with a brown tint, different shades blurring and brushed over by wider swirling patterns. The dominant figure is the lighter skinned woman, a movement in the frame from darker to lighter noticeable in other Brunias paintings, reflecting the mixture of white and black ancestry right from the start of The Fifth Figure. Derek Walcott could have been talking about this painting when he wrote, "Deprivation is made lyrical and twilight, with the patience of alchemy, almost transmutes despair into virtue. In the tropics, nothing is lovelier than the allotments of the poor, no theatre as vivid, voluble, and cheap." (What the Twilight Says: Essays) This lyricism is emptied out in the prose accounts of The Fifth Figure - the dancers reveal their own steps, the traps and escapes of their lives:

I learnt how to pick mangoes with Nana, how to aim and throw straight, at the stem, not the fruit, so they wouldn't suffer a bruising, and now I know if the children come back, I shall stone them down like ripe mangoes.Each section reads like a family testament. The speed of 80 pages to contain five generations leaves the impression of an album, turned through. Here great-granddaughter Sarah echoes Susu above:

I walk home quick

As soon as the school bell ring

But a group of boys from the common

Now following me all the way

They shout at me

They pull my hair

They throw my books in the bush

One day as I reach the gate

I pick up a stone and fling

Just like I use to fling in Hillside

Fling pon the mango tree