James Wilkes, A DeTour

----------------------------------------------

November 2006 8 postcard poems £4.50 inc p+p. Renscombe Press

Reviewed by Edmund Hardy

----------------------------------------------

Where J. M. Coetzee dropped the 'De' for his Crusoe-rework, Foe, James Wilkes has picked it up & used it to interrupt A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain as a series of 8 postcards, A DeTour. Defoe's Tour, published between 1724 and 1727, is the culminating work of this man's cartographic imagination, Defoe's sense that territory must be eyed so that its potential for production and for delight could be assayed. It is the country's state at the end of a "century of revolution" (from James to Anne, or in prose style, Browne to Defoe), as Christopher Hill suggests: "We are already in the modern world - the world of banks and cheques, budgets, the stock exchange, the periodical press, coffee-houses, clubs, coffins, microscopes, shorthand, actresses, and umbrellas. It is a world in which governments put first the promotion of production, for policy is no longer determined by aristocrats whose main economic activity is consumption. Defoe's eye was always wide open for ways in which the national wealth could be increased: he knew this would interest his readers." (Hill, The Century of Revolution, Routledge 2002, p305). It was the century in which money began to talk.

Defoe's Tour was popular in the 18th century - it was cut and updated, it was treated as gazetteer, an English Pausanias who provided such a variety of information that the Tour, though fading from popularity, would be continually quoted as a source. For his rework, Wilkes cuts 8 postcards from Defoe's 13 letters; each postcard works differently, taking small pieces from the Tour, filtering them into a contemporary style. 'A Postcard from the Black Mountains', pictured above (though printed in red in the final set), looks like a poster for a cheap nightclub advertising Wednesday night as "Defoe Nite". This is the only postcard in which Defoe is reworked out from text; a ploughed eye, a trace of the South Sea Bubble in its aftermath? It is not the free-fall eye of Leslie Scalapino's own prose epic Defoe.

'A Postcard from Rochester' reduces Defoe's famed aptitude for summing a commercial centre into two wavy lines which could resemble a running animal -

or the tentacles of the urban octopus - while other postcards present lists which provoke comparisons to a Richard Long "walk", or description re-lineated, or re-cut to inhabit a scape of faint gothic traces, "sweet as Herbs soft as Velvet", an atmosphere limned, it seems, from Defoe's own retelling of many a local tale. Defoe's work is already stuffed with the business of people; his prose style, its loose syntax in which every sentence reaches out down several channels, sketches in a map: Wilkes, by cutting out phrases and placing them on the white of postcards, places a blindfold over this map.

'A Postcard from the Markets of London' finds that

where Business is done- one postcard in which Wilkes really rises up to the cut which striates Defoe's "business of description": the break between the non-economic material life and the baffling economic engines of currency, commerce, volatility and equipment; the animating break of markets which, as they grew, caused revolutions.

are Monsters for Magnitude

Time out of Mind

To receive 8 elegant postcards from Defoe through the post (with appropriate intervals between arrivals) also conceives of the contemporary postal system as an atemporal circulating set in which the profiguration of mutable texts takes talkative capital "out of Mind".

*

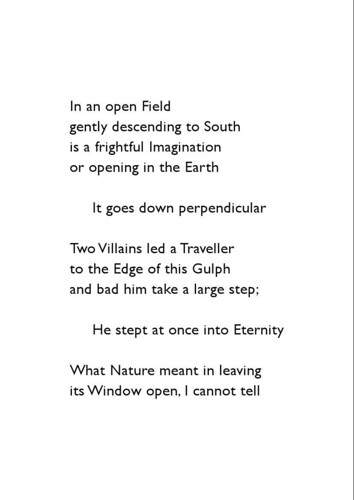

We can look into Wilkes' workshop by comparing this 'Postcard from Elden Hole'

with the complex from which it is drawn:

But I must dwell no longer here, however pleasant and agreeable the place. The remaining article, and which, I grant, we may justly call a WONDER, is Elden Hole: The description of it, in brief, is thus: In the middle of a plain open field, gently descending to the south, there is a frightful chasme, or opening in the earth, or rather in the rock, for the country seems thereabouts to be all but one great rock; this opening goes directly down perpendicular into the earth, and perhaps to the center; it may be about twenty foot over one way, and fifty or sixty the other; it has no bottom, that is to say, none that can yet be heard of. Mr. Cotton says, he let down eight hundred fathoms of line into it, and that the plummet drew still; so that, in a word, he sounded about a mile perpendicular; for as we call a mile 1760 yards, and 884 is above half, then doubtless eight hundred fathoms must be 1600 yards, which is near a mile.

This I allow to be a wonder, and what the like of is not to be found in the world, that I have heard of, or believe. And would former writers have been contented with one wonder instead of seven, it would have done more honour to the Peak, and even to the whole nation, than the adding five imaginary miracles to it that had nothing in them, and which really depreciatcd the whole.

What Nature meant in leaving this window open into the infernal world, if the place lies that way, we cannot tell: But it must be said, there is something of horror upon the very imagination, when one does but look into it; and therefore tho' I cannot find much in Mr. Cotton, of merry memory, worth quoting, yet on this subject, I think, he has four very good lines, speaking of his having an involuntary horror at looking into this pit. The words are these:

For he, who standing on the brink of hell,

Can carry it so unconcern'd and well,

As to betray no fear, is certainly

A better Christian, or a worse than I.

COTTON'S Wonders of the Peak .

They tell a dismal story here, of a traveller, who, enquiring his way to Castleton, or to Buxton, in a dark night, two villains offer'd to guide him; but, intending to rob him, led him to the edge of this gulph, and either thrust him in, or persuaded him to believe there was a little gall of water, and bad him take a large step, which the innocent unfortunate did, not mistrusting the treachery, and stept at once into eternity; a story enough to make the blood run cold through the heart of those that hear it told, especially if they know the place too: They add, that one of these villains being hanged at Derby some years after for some other villany, confess'd this murther at the gallows.

- Daniel Defoe, A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain, Letter 8, Part 2: The Peak District