James Wilkes

Alstonefield: a journal

12 September. Part 1, pp. 5-8, verses 1-9

'A special and slight enclosure is set'. This is night in the churchyard, and the poem too, with its narrow stanzas that I go through, back and forth, trying to get the words to settle into an interpretation. What's the 'theatre of eyes' that 'flickers and dies' in rhyme? The stars, or mica glinting in granite headstones? But that's the wrong kind of rock, it should be limestone… From the letter that forms the preface comes a 'theatre of outrageously manipulated light'.

The old names on the gravestones are a farewell that 'sets standards of dealing'. Their measure is set against other things, the 'mirror flashes' of a world coated in speed, a mirror that also 'coats the bank'. Capitalism and velocity, over the language that you can't 'secretise' because 'the world is watching'. So the graveyard is a public stage, where language is stripped in the names of the dead, the moon as the 'direct file'. But what about writing and secrecy? Art as a publicly private activity – as in Schwitters' Merzbau. This is dense, allusive and elusive work, and keeps a certain privacy in its shifting grammar – to be judged against the yardstick of remembrance.

Later there is an auditory hallucination, a folk song, mother to child. 'Poor rabbit'. I receive a shock of emotion from those two words.

13 September. Part 2, pp. 9-14, verses 10-24

'The rose of time in the earth pocket'. A few variations on this line: the crocus of seasons in the sky belt, the carnation of space in the desert clasp, the jasmine of thought in the river tassel.

A globe of love is 'like / a repair depôt that continues through governments / and wars at the end of a small back road where / carefree labourers stroll around dark and competent.' The extension of simile into a small theatre, the abstract 'love' taking on the contours of this scene, which extends over three lines and has people in it too, a living diorama.

'I think my dressing gown is a thin and crucial history'. Some other memorable dressing gowns: 'Lying down in my father's grey dressing gown / its red cuffs over my eyes…' (Douglas Oliver, The Infant and the Pearl); 'Suddenly the dressing-gown walked quickly towards him. "Understand me!" said the dressing-gown. "No attempts to hamper me, or capture me! Or –" Kemp's face changed a little. "I thought I gave you my word," he said.' (HG Wells, The Invisible Man).

As an aside, these lines leapt out from the pages I was scanning: 'It was strange to see him smoking; his mouth, and throat, pharynx and nares, became visible as a sort of whirling smoke cast.' Wells' fantasy works to reveal the hidden spaces of the human body, performing a sculptural endoscopy. Last week I visited the Wellcome Collection, and saw Annie Cattrell's sculptures of amber resin set in transparent plastic blocks. The strange coagulated blobs take their form from fMRI scans of brain activity: casts of seeing, hearing, smelling, touching, tasting. Actualising a state, a verb.

14 September. Part 3, pp. 15-19, verses 24-36

Stones, globes, lines, light, paper, ardour, surfaces, bowing, crossing a river on a wooden footbridge, an oval meadow, wine, walking finger inter finger, long-eared sheep.

17 September. Part 4, pp. 20-22, verses 36-44

There are gods in this section, who in their first mention have 'birth graves', 'where lives converge'. Later, they have 'god-grounds' and leave 'god tracks', appearing as something of a cross between Lares and wild animals. In his interview with Keith Tuma in The Gig 4/5 and Jacket 11 Peter Riley has this to say about such words: 'The "religious" vocabulary – soul, redemption, etc. – remains valid as indeed it remains in common parlance, while the religious structures fall into dereliction.' So perhaps these gods should be read as folk religious terms, and be treated like folk psychological terms such as 'belief', 'desire', 'fear'.

Verse 40 has in its first line, 'Serious message get on with your business'. This makes me think of Defoe, and his closing off of asides or stories with the invocation of business: 'but to return to the business in hand', 'but it is not my business', 'but my business is the present state of things' (from A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain). Riley's next lines elaborate that his business consists in being 'here in all kinds of weathers / and walk and walking trade my pulse for / notices of souldom in geophysical latitude / spurning the news.' So far, this is less Defoe than Richard Long, whose journeys privilege the individual and elemental over the social and political. But then the lines cut a different way: 'The politics of this / carries hope like a feather on the palm: / my country tracks are crossed in oil and / its inhering slaughter.' The feather on the palm imposes a slowness and care in proceeding if it is not to be lost, as the crossing of oil conjures the webs of global politics in which all are implicated. 'The oval meadow / trusts minds only, the broken ring-dance / humanises permanent assets to the world'. Is the oval meadow the Peaks? And what is the broken ring-dance? Is it related to the ex-Yugoslavian kolo?

19 September. Part 5, pp. 23-28, verses 45-61

The 'rose of time' is back, and I shouldn't gloss over it. I'm still uncertain about its meaning, as it emerges this time from a car boot sale in the rain, as 'every necessary transaction brandishes / the rose of time, triumphantly above / the stalls of love'.

It has a vague affinity in my mind with Lorca, though now I've looked it up the lines I was thinking of are completely different: 'Ya los musgos y la hierba / abren con dedos seguros / la flor de su calavera.' (Now the mosses and the grass / open with sure fingers / the flower of his skull.) Having failed, I return to Alstonefield: 'Then the heart and the / mountain range are one.' Ossified and distant.

'Let me wander still in the open / fields of failure, where the linnet coughs at eve / and the daffydil hides it condom, let me live // longer in the long pain.' Failure as an open field, that keeps its potentiality and space for manoeuvre. Shortly after, failure is something to wrap oneself in, during a walk upstream in the dark.

20 September. Part 5, pp. 29-34, verses 62-79

The ambiguous relationship with the pastoral. 'And loud and long the constant fall / and strike of water on itself fills the air / on all sides with a continual sounding' – sounds very Lakeland. Yet earlier Riley is 'waiting in the rain / for something better than pastoral, some- / thing less fairground and more circus'. Waiting for a performance not a side show?

As a response I'm going to try a mash-up (chimera) of the beginning of The Prelude with nouns from Douglas Oliver's An Island That is All the World and verbs from Geoffrey Hill's An Apology for the Revival of Christian Architecture in England.

Oh there is access in this gentle area,

A past that while it returns my thriller

Doth rise half-conscious of the movie it is

From the green step-son, and from yon azure VCR.

Whate'er its desk, the soft charm can put

To none more grateful than to me; burned

From the vast ogham script, where I long had twitched off

A discontented friend: now free,

Free as a letter 'B' to rejoice where I haunt.

What 'bees' shall be me? in what obsessions

Shall be my child? underneath what chant

Shall I rip my word? and what clear poetry

Shall with its nature huddle me into fate?

The Kind bulge all before me. With a loss

Joyous, nor scared at its own Renaissance,

I cram about; and should the chosen meanings

Batter nothing better than a wandering nature,

I cannot swing my state of mind. I am again!

Minds of emotion and daughters of the birth

Live fast upon me: it is known,

That stress of my own unnatural vividness,

The heavy perception of many a weary attack

Not mine, and such as were not known for me.

Long Imp of thought (if such bold lives flourish

With any colour of human knives),

Long voices of friends and undisturbed saws

Puts down mine in ears; whither shall I grow,

By thriller movies or fears, or through trackless film,

Up bodies or down, or growing some floating whippings

Upon the murderess doffing me out my hands?

Not entirely sure if this works, or what it proves. It sounds a bit like I'm taking the piss, which isn't my intention at all. As a homage to Riley it fails I think, because chance operations play no part in his highly sculpted poetry, even assuming I'd selected the right ingredients. As a fragment in its own right, it has its moments.

22 September. Part 5, pp. 35-40, verses 80-97

The water's 'long tones sing themselves' in yesterday's section, and already the pressure of the material is pushing this journal out of shape. I need to say something at least about song and the way it opened out a few pages back, before I get to the heart of the section I've just read, the night dance through the mist with a giant rabbit.

Song as request and prayer is proposed in all seriousness, but then a note of ambivalence and even satire creeps in. 'Grant us peace, time and space / fit for thought […], give us a chance. I pray / for the future of the Ba-Benzélé pygmies / of equatorial Africa what else can I do?' The unvoiced and surely invited riposte is probably quite a lot, in practical terms. A couple of lines later, singing 'waley waley love is unjust' in a parody of the self-absorption of love songs.

The best context for song seems to come from another Pygmy tribe, the Aka, who do their 'polyphonic hoquetting' simply 'because "this is what we do now".' An unforced song, like the lament, which a few verses later 'trembles through the entire economy torn apart.' This is a point where two of the poem's dominant colours are knotted into display.

The oval meadow reveals itself as a place where river goes one way and cliffs the other, making a 'mandorla in middle night, / full of river mist to chest height.' Within this almond mandala, the narrator dances with the rabbit, his / her strong 'clasp behind my neck where ghosts make / their love'.

'Look this is a serious poem why am I / waltzing with a mammal?' Because it's one of those scenes that lodges deep inside the imagination. Because in the 'shared space' of this dance is the crux of the poem's concern, crossing between one and many, human and inhuman, self and beloved; living right.

I like the vision of a civic socialism as something very natural (that is, divined in the non-human), as in 'the great / omnibus of the rain'. Why is this attractive? Because it makes the difficult job of making a fair society seem easy. Because the metaphor's stretch confirms my own political leanings, short-circuits them as 'natural', and obviates the need to justify them to others. It is Arcadian not Utopian. But look, I've run too far with this small figure – in context, it's exclaimed at a point when 'delight transcends critique' and should be treated like an expression of joy not a persuasive device. And as we have been warned earlier, 'poetry occupies its / moment completely, like heroin, it is deeply / convincing'. So here the poet is smacked out on delight. Treat with caution.

24 September. Part 5, pp.41-46, verses 98-115

'The rest of us continue like street lamps or / endoscopes in the bowel of day.' Improbably, my oblique foray into endoscopy 11 days ago is justified.

'O Delvig, what do we become? / Nothing, a great city of it, built up from / a night point.' The sense of nothing as substantive, a great city – I get this when I think of Auden's 'poetry makes nothing happen', stressing in my head the words nothing and happen, making it an act of creating a no-thing. This is a wilful misreading I know. Modifying his words in my gut.

Seen from above the oval meadow is compared to 'real space like a Piazza del Popolo'. A few lines later, 'meetings are real / when just, tonight just me and the night creatures'. Just as in fair, and just as in singular. This all seems to be gathering pace towards a space for democracy where equals meet face-to-face, and indeed in a few verses' time we get a 'public space, a meeting-place / of conflicting hearts on limestone paving', following 'an argument kept / alive by interjection of honesty and pride'.

It's not too much of a stretch to connect this to Chantal Mouffe's agonistic pluralism, which acknowledges the antagonism inherent in social relations and the political, and seeks to create processes to 'domesticate' this as agonism, a conflict between adversaries rather than enemies. Emotions and confrontations, Riley's 'conflicting hearts' are essential to a healthy democratic process.

But is the architecture of the mercantile city-state really the space to produce 'real' meetings, and an authentic (participatory, unfinished) democracy? The poem can appropriate it as such, I think, emptying it like a de Chirico painting then re-laying the webs of relations that give it meaning. A piazza has just the right dimensions and flatness to be recycled, in the imagination at least, as a new forum. I think train stations hold this possibility too, and sometimes imagine Waterloo as a post-diluvian meeting-place surrounded by longboats.

Then Shostakovich's ghost appears in a 'horrible' check sports-jacket.

12 September. Part 1, pp. 5-8, verses 1-9

'A special and slight enclosure is set'. This is night in the churchyard, and the poem too, with its narrow stanzas that I go through, back and forth, trying to get the words to settle into an interpretation. What's the 'theatre of eyes' that 'flickers and dies' in rhyme? The stars, or mica glinting in granite headstones? But that's the wrong kind of rock, it should be limestone… From the letter that forms the preface comes a 'theatre of outrageously manipulated light'.

The old names on the gravestones are a farewell that 'sets standards of dealing'. Their measure is set against other things, the 'mirror flashes' of a world coated in speed, a mirror that also 'coats the bank'. Capitalism and velocity, over the language that you can't 'secretise' because 'the world is watching'. So the graveyard is a public stage, where language is stripped in the names of the dead, the moon as the 'direct file'. But what about writing and secrecy? Art as a publicly private activity – as in Schwitters' Merzbau. This is dense, allusive and elusive work, and keeps a certain privacy in its shifting grammar – to be judged against the yardstick of remembrance.

Later there is an auditory hallucination, a folk song, mother to child. 'Poor rabbit'. I receive a shock of emotion from those two words.

13 September. Part 2, pp. 9-14, verses 10-24

'The rose of time in the earth pocket'. A few variations on this line: the crocus of seasons in the sky belt, the carnation of space in the desert clasp, the jasmine of thought in the river tassel.

A globe of love is 'like / a repair depôt that continues through governments / and wars at the end of a small back road where / carefree labourers stroll around dark and competent.' The extension of simile into a small theatre, the abstract 'love' taking on the contours of this scene, which extends over three lines and has people in it too, a living diorama.

'I think my dressing gown is a thin and crucial history'. Some other memorable dressing gowns: 'Lying down in my father's grey dressing gown / its red cuffs over my eyes…' (Douglas Oliver, The Infant and the Pearl); 'Suddenly the dressing-gown walked quickly towards him. "Understand me!" said the dressing-gown. "No attempts to hamper me, or capture me! Or –" Kemp's face changed a little. "I thought I gave you my word," he said.' (HG Wells, The Invisible Man).

As an aside, these lines leapt out from the pages I was scanning: 'It was strange to see him smoking; his mouth, and throat, pharynx and nares, became visible as a sort of whirling smoke cast.' Wells' fantasy works to reveal the hidden spaces of the human body, performing a sculptural endoscopy. Last week I visited the Wellcome Collection, and saw Annie Cattrell's sculptures of amber resin set in transparent plastic blocks. The strange coagulated blobs take their form from fMRI scans of brain activity: casts of seeing, hearing, smelling, touching, tasting. Actualising a state, a verb.

14 September. Part 3, pp. 15-19, verses 24-36

Stones, globes, lines, light, paper, ardour, surfaces, bowing, crossing a river on a wooden footbridge, an oval meadow, wine, walking finger inter finger, long-eared sheep.

17 September. Part 4, pp. 20-22, verses 36-44

There are gods in this section, who in their first mention have 'birth graves', 'where lives converge'. Later, they have 'god-grounds' and leave 'god tracks', appearing as something of a cross between Lares and wild animals. In his interview with Keith Tuma in The Gig 4/5 and Jacket 11 Peter Riley has this to say about such words: 'The "religious" vocabulary – soul, redemption, etc. – remains valid as indeed it remains in common parlance, while the religious structures fall into dereliction.' So perhaps these gods should be read as folk religious terms, and be treated like folk psychological terms such as 'belief', 'desire', 'fear'.

Verse 40 has in its first line, 'Serious message get on with your business'. This makes me think of Defoe, and his closing off of asides or stories with the invocation of business: 'but to return to the business in hand', 'but it is not my business', 'but my business is the present state of things' (from A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain). Riley's next lines elaborate that his business consists in being 'here in all kinds of weathers / and walk and walking trade my pulse for / notices of souldom in geophysical latitude / spurning the news.' So far, this is less Defoe than Richard Long, whose journeys privilege the individual and elemental over the social and political. But then the lines cut a different way: 'The politics of this / carries hope like a feather on the palm: / my country tracks are crossed in oil and / its inhering slaughter.' The feather on the palm imposes a slowness and care in proceeding if it is not to be lost, as the crossing of oil conjures the webs of global politics in which all are implicated. 'The oval meadow / trusts minds only, the broken ring-dance / humanises permanent assets to the world'. Is the oval meadow the Peaks? And what is the broken ring-dance? Is it related to the ex-Yugoslavian kolo?

Only the rapid rhythm of the 'kolo' could provoke that blank stupor in the eyes of the dancers, which is the result of physical satisfaction. [...] My countrymen used the rhythm to wipe away all meanings and all borders, including national ones and emotional ones (which was frightening).Given the context, a Yugoslav connection seems unlikely. But still, interesting to wonder what role a stupor induced by walking might play. Does it produce the mirrored visions of the last three stanzas of this section, where the 'I' of the poem walks back to a B&B, a guest house, and a teacher in turn, and finds 'the god-grounds are equable', 'the god tracks converge', and 'the heart light is shielded'?

– Dubravka Ugrešić, The Culture of Lies.

19 September. Part 5, pp. 23-28, verses 45-61

The 'rose of time' is back, and I shouldn't gloss over it. I'm still uncertain about its meaning, as it emerges this time from a car boot sale in the rain, as 'every necessary transaction brandishes / the rose of time, triumphantly above / the stalls of love'.

It has a vague affinity in my mind with Lorca, though now I've looked it up the lines I was thinking of are completely different: 'Ya los musgos y la hierba / abren con dedos seguros / la flor de su calavera.' (Now the mosses and the grass / open with sure fingers / the flower of his skull.) Having failed, I return to Alstonefield: 'Then the heart and the / mountain range are one.' Ossified and distant.

'Let me wander still in the open / fields of failure, where the linnet coughs at eve / and the daffydil hides it condom, let me live // longer in the long pain.' Failure as an open field, that keeps its potentiality and space for manoeuvre. Shortly after, failure is something to wrap oneself in, during a walk upstream in the dark.

20 September. Part 5, pp. 29-34, verses 62-79

The ambiguous relationship with the pastoral. 'And loud and long the constant fall / and strike of water on itself fills the air / on all sides with a continual sounding' – sounds very Lakeland. Yet earlier Riley is 'waiting in the rain / for something better than pastoral, some- / thing less fairground and more circus'. Waiting for a performance not a side show?

As a response I'm going to try a mash-up (chimera) of the beginning of The Prelude with nouns from Douglas Oliver's An Island That is All the World and verbs from Geoffrey Hill's An Apology for the Revival of Christian Architecture in England.

Oh there is access in this gentle area,

A past that while it returns my thriller

Doth rise half-conscious of the movie it is

From the green step-son, and from yon azure VCR.

Whate'er its desk, the soft charm can put

To none more grateful than to me; burned

From the vast ogham script, where I long had twitched off

A discontented friend: now free,

Free as a letter 'B' to rejoice where I haunt.

What 'bees' shall be me? in what obsessions

Shall be my child? underneath what chant

Shall I rip my word? and what clear poetry

Shall with its nature huddle me into fate?

The Kind bulge all before me. With a loss

Joyous, nor scared at its own Renaissance,

I cram about; and should the chosen meanings

Batter nothing better than a wandering nature,

I cannot swing my state of mind. I am again!

Minds of emotion and daughters of the birth

Live fast upon me: it is known,

That stress of my own unnatural vividness,

The heavy perception of many a weary attack

Not mine, and such as were not known for me.

Long Imp of thought (if such bold lives flourish

With any colour of human knives),

Long voices of friends and undisturbed saws

Puts down mine in ears; whither shall I grow,

By thriller movies or fears, or through trackless film,

Up bodies or down, or growing some floating whippings

Upon the murderess doffing me out my hands?

Not entirely sure if this works, or what it proves. It sounds a bit like I'm taking the piss, which isn't my intention at all. As a homage to Riley it fails I think, because chance operations play no part in his highly sculpted poetry, even assuming I'd selected the right ingredients. As a fragment in its own right, it has its moments.

22 September. Part 5, pp. 35-40, verses 80-97

The water's 'long tones sing themselves' in yesterday's section, and already the pressure of the material is pushing this journal out of shape. I need to say something at least about song and the way it opened out a few pages back, before I get to the heart of the section I've just read, the night dance through the mist with a giant rabbit.

Song as request and prayer is proposed in all seriousness, but then a note of ambivalence and even satire creeps in. 'Grant us peace, time and space / fit for thought […], give us a chance. I pray / for the future of the Ba-Benzélé pygmies / of equatorial Africa what else can I do?' The unvoiced and surely invited riposte is probably quite a lot, in practical terms. A couple of lines later, singing 'waley waley love is unjust' in a parody of the self-absorption of love songs.

The best context for song seems to come from another Pygmy tribe, the Aka, who do their 'polyphonic hoquetting' simply 'because "this is what we do now".' An unforced song, like the lament, which a few verses later 'trembles through the entire economy torn apart.' This is a point where two of the poem's dominant colours are knotted into display.

The oval meadow reveals itself as a place where river goes one way and cliffs the other, making a 'mandorla in middle night, / full of river mist to chest height.' Within this almond mandala, the narrator dances with the rabbit, his / her strong 'clasp behind my neck where ghosts make / their love'.

'Look this is a serious poem why am I / waltzing with a mammal?' Because it's one of those scenes that lodges deep inside the imagination. Because in the 'shared space' of this dance is the crux of the poem's concern, crossing between one and many, human and inhuman, self and beloved; living right.

I like the vision of a civic socialism as something very natural (that is, divined in the non-human), as in 'the great / omnibus of the rain'. Why is this attractive? Because it makes the difficult job of making a fair society seem easy. Because the metaphor's stretch confirms my own political leanings, short-circuits them as 'natural', and obviates the need to justify them to others. It is Arcadian not Utopian. But look, I've run too far with this small figure – in context, it's exclaimed at a point when 'delight transcends critique' and should be treated like an expression of joy not a persuasive device. And as we have been warned earlier, 'poetry occupies its / moment completely, like heroin, it is deeply / convincing'. So here the poet is smacked out on delight. Treat with caution.

24 September. Part 5, pp.41-46, verses 98-115

'The rest of us continue like street lamps or / endoscopes in the bowel of day.' Improbably, my oblique foray into endoscopy 11 days ago is justified.

'O Delvig, what do we become? / Nothing, a great city of it, built up from / a night point.' The sense of nothing as substantive, a great city – I get this when I think of Auden's 'poetry makes nothing happen', stressing in my head the words nothing and happen, making it an act of creating a no-thing. This is a wilful misreading I know. Modifying his words in my gut.

Seen from above the oval meadow is compared to 'real space like a Piazza del Popolo'. A few lines later, 'meetings are real / when just, tonight just me and the night creatures'. Just as in fair, and just as in singular. This all seems to be gathering pace towards a space for democracy where equals meet face-to-face, and indeed in a few verses' time we get a 'public space, a meeting-place / of conflicting hearts on limestone paving', following 'an argument kept / alive by interjection of honesty and pride'.

It's not too much of a stretch to connect this to Chantal Mouffe's agonistic pluralism, which acknowledges the antagonism inherent in social relations and the political, and seeks to create processes to 'domesticate' this as agonism, a conflict between adversaries rather than enemies. Emotions and confrontations, Riley's 'conflicting hearts' are essential to a healthy democratic process.

But is the architecture of the mercantile city-state really the space to produce 'real' meetings, and an authentic (participatory, unfinished) democracy? The poem can appropriate it as such, I think, emptying it like a de Chirico painting then re-laying the webs of relations that give it meaning. A piazza has just the right dimensions and flatness to be recycled, in the imagination at least, as a new forum. I think train stations hold this possibility too, and sometimes imagine Waterloo as a post-diluvian meeting-place surrounded by longboats.

Then Shostakovich's ghost appears in a 'horrible' check sports-jacket.

27 September. Part 5, pp. 47-52, verses 116-133

The narrator grabs hold of the composer's shoulders, and demands to be told what it was all for (the 'production unit / that doesn't know how to stop', the 'prison farms', the 'acrid / smoke'). Shostakovich's non-answer is a 'sound in the air of his head', a 'yes / from which the heart has been removed'. The same outer acquiescence that the state demanded, and got. Then, he meets the poet's demand of 'musician, be different' with 'let me fail'. A counter-demand to allow him failure, to make allowance for his doing what they asked.

28 September. Part 5, pp. 53-58, verses 134-151

An index for today's section (tribute to Stacy Doris's index for Lisa Robertson's Seven Walks):

50p, 56

bouquet, small, 53

cave, ancestral, 58

cave-shaft, 58

dream of a nationless economy, 57

dream, time like a rolling, 56

floreation on the walls, 58

fly agaric, blooms of, 55

geology of violent disruption, 57

grave, cosy, 57

harmonium, old, 53

highway, see public highway

'in the original orthography', 54

inlier, ridgeback sandstone, 53

jacket, old tweed, 58

lame man's Polish mother, 53

'lowland broth', 56

moles, anthropomorphic, 57, 58

pale moving blur, a, 53

pine cone, see 'tight like a pine cone'

potted herbs, 56

'promises are a bridge', 53

'promises are acrobats', 53

'promises take my hand', 54

public highway, recently privatised, 55

road, long, 54

road, starlit, 53

roads, rolling in cloudy certainty down long straight, 54

Seán 'ac Dhonncha, 58

sheltering arcs, connoisseur of, 57

'sparks rusticate the night sky', 58

stones and fibre, 56

telephone box, public, 56, 57

'tight like a pine cone', 56

time as dream, see dream, time like a rolling

time, vast stretches of, 57

time's cynicism, 54

tin chapel, 53, 54

tin shack, 54

trees gathering over me, 56

unconcealed thrones, my words are, 55

wood, caught in this, 55

woods, private, 55

Zaire, artisans of, 58

1 October. Part 5, pp.59-68, verses 152-181

(The narrator splits in two – this journal entry follows self 1 as it takes the path along the river at the foot of Ecton Hill.)

Looking up at it I know it ticks within, I knowI wanted to write out this long sentence that spans the end of one verse and the beginning of the next – actually, I wanted to write out only 'O my son // Absalon', to pick up on the variant spelling as a pointer towards a motet by Josquin Desprez, but then I was attracted by the cadence of the passage's tail, and then an instinct to completeness made me type out the lines preceding the 'O'. And I'm glad I did, because this sentence embodies a polyphonic principle, where neither an economic nor a lyric voice dominates the melody, but rather it is passed between them. And the sentence is not self-contained, not only does it expand itself beyond breath with the pause at the verse-break, but the 'it' in the first line passes the chain of reference back up to the 'empty hill' (mined for copper), that the narrator is walking past.

supply takes most of the energy, I know my right

is fallen through surface, O my son

Absalon, would I had died before the warlords

began to rule the earth and robotise the fair contours

of the human map, our many ways of falling.

There's a version of Desprez's 'Si j'ay perdu mon amy' on the album Cruzando El Río by Radio Tarifa. And happily, Radio Tarifa's Arab-Andalusian music connects Africa and Europe in a way that parallels this poem's leaping between Central Africa, with the Aka or the Dorze's polyphonic singing, and its evocation, for example, of 'miners / carolling under the hill'. (Vaughan Williams transcribed the Corpus Christi Carol in Castleton, we are told in Riley's notes, and was informed that 'every Christmas Eve the lead miners […] would descend to the lowest part of the mine, and in an open space there set a candle on a piece of lead ore, and sing the carol sitting round it in a circle'.)

But to return to the business in hand. Nature of return: oblique, partial. Wikipedia is quite good on Desprez (or des Prez). Here are a few intercuttings from above-named source that are interesting in relation to this poem and its polyphony:

Josquin made extensive use of "motivic cells" in his compositions, short, easily-recognizable melodic fragments which passed from voice to voice in a contrapuntal texture, giving it an inner unity:'hold harm at arm's length'; 'harmless human'; no success without harm'.

The Missa L'ami Baudichon, probably his first mass […] is based on a secular – indeed ribald – tune:'Am I not a plain speaking man, furry friend?'

[In Paraphrase masses] the source material […] is embellished, often with ornaments:'O Shallow Brown, you're going to leave me. // I was interested precisely in staying put, I didn't want / to rend or bend or pump up anyone's heart, I never / traded in disappointment; the only departure I know / is of everything: Italian socialism, art, mossy stones…'

Almost all of Josquin's motets use some kind of compositional constraint on the process; they are not freely composed:'…like a hibernating toad / but I have gone the wrong way and there's a knight in the road.'

He wrote many of his motets for four voices, […] and he also was a considerable innovator in writing motets for five and six voices.There are different ways of doing polyphony. It's the difference between the unknown artisan subsumed within a tradition (as in polyphonic folk song) and the overseer-composer whose name is attached, if only provisionally (as in Renaissance motets or masses) – and this second condition obtains also for poets, even those who, with the lightest of touches, arrange voices – e.g. Charles Reznikoff, John Seed.

Perhaps translators most closely achieve the anonymity of folk singers – and this against their will, in general. The attractive myth of direct transmission, the unseen hand, works against their acknowledgment.

2 October. Part 5, pp.69-80, verses 182-218

For today's entry I'd like to try an exercise in memory. I'm going to read through these twelve pages once only and then write as nearly as I can what sticks in my head.

Reaching page 74 I realise that each successive verse is wiping my memory of the last, so here's what I remember so far:

I remember Schubert make us tempiettos for our fear

I remember various ailments: a bleeding nose, a hernia, chronic bronchitis

I remember the legs are the only part that still works right

I remember he wanted to live in a loft by a mill pond

I remember it was a place he could have been happy, or gone psychotic with loneliness and not bothered anyone

I remember it wasn't for sale anyway, and he didn't have any money anyway

I remember the wind driving snot up his nostrils

I remember he crouched knees to cheek in the holy boundary of a wall

I remember the Beaker posture

I remember him suddenly feeling peckish and unwrapping an egg sandwich

I remember there was quite a lot about the economy, though I forget the detail

I remember his mother and father in the postwar

Here's what I wanted to remember and failed:

I forgot that Schubert built not made the tempiettos

I forgot wrapping my future in a napkin

I forgot the shoes of this text, recommended for poetical discretion, are Clarks

I forgot a tape-looped starling

I forgot earth-colours riven with occulted light

I forgot the author of unsent complaints

I forgot nothing left but thin sticks of bone in hillside grass

I forgot the rosie niplet of her breast

I forgot the cream of light fell to the dark earth writing walls and contracts

I forgot the Scythian word-processor in the stone mound

I forgot we refuse to die into this economy

I also mis-remembered quite a lot.

4 October. Part 5, pp. 81-86, verses 219-236

I'm lagging behind again here, I want to go back to the rest of yesterday's section and an 'enemy' that is mentioned but keeps shifting ground. Back on p.49 the 'only / adversary' was death, but the NHS heart specialist now finds that the enemy is 'not death but life', as service 'de Humilitate' to the Christ-like 'human fact' is sold off, broken up by soldier-managers who do this 'out of love'. (And here we get a better idea of what Riley might mean by love, this ambiguous force that 'serves no / purpose but its own' and also 'raised the death camps' – it is something they do 'not for themselves, that's the point. It's an idea, a vision.')

Other enemies round here are the economy (p.74), the earth (p.83), and the 'old enemy' (p.82).

The 'dragons of earth' appear to self 2 at the top of the hill, with their 'silence, their fear, / their no-theology'. As he makes his way down the hill, they become hidden, 'dragons of day' and 'dragons of result'.

Calvino reads the dragon, of St. George fame, as psyche, a 'part of ourselves that we must judge'; as 'dragon-enemy in the daily massacre of the city' (The Castle of Crossed Destinies).

In the calm before the two selves 'merge into each other silently', self 2 passes by bushes which state 'ways of doing good in the world' – ways of living – in 'the available space / of the night'. Each space is a stanza, reinforcing the affinity between the form and night's space. We've gained a little room at least, through all this, as the verses lengthen their stride. Six bushes state their cases in full, and then we are ushered on.

5 October. Part 5, pp.87-101, verses 237-279

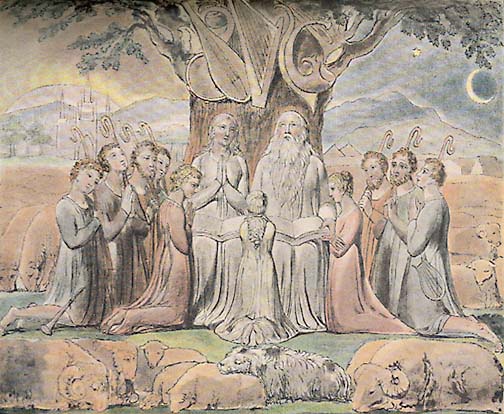

William Blake, Job and His Family

'The old flute hangs by the hearth

waiting to be repaired, to trill out over the darkness

and burdens of sorrow like the lark in the morning'

*

Samuel Palmer, The Skylark

'…the morning star, the lark

on high. There it goes, like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

on one of his shaking ascents and the sign of

tomorrow is a fat man shrinking into the sky'

*

Joseph Webb, The Shepherd's Haven

'Skinheads falling into

purity with big thumps. Hear the thumps and weep'

'…skinheads falling to earth

all round me like lambs dropped by eagles'.

*

Hurt and harm – for the entire poem these words are in process. I mean they are continually sounded in different combinations and contexts, approaching but never completing their meaning. As 'loss is continual', so is what causes it. And no resolution, just an end, 'death as failure, as 'failure to continue'.

In the next section, as at certain other points, I've mixed up the order of the passages I quote, cutting back and forward through the time of reading. These temporal hernias often occur when memorable phrases poke through a weakened spot in the muscular wall of consciousness. The good news is they are not usually fatal.

No resolution, but there is a coda, a sense of movement moving to the right point for an end, despite talk of just having to 'see it through […] to the end of the book'. It's something less arbitrary than this, as the poem becomes an aubade, farewell at dawn to the 'much missed person', through the collapse and tiredness, farewell to the dove (a 'bundle of nerve') going 'right out of the world' –

'Much missed person my hope / is always there where my heart's capital is sunk.'

James Wilkes